Not long after I started studying Korean, I signed up for a Japanese class, Japanese being the closest language I could find classes for in Santa Barbara at that time, in hopes of meeting a Korean international student with whom to practice the one I really wanted to learn. I soon did, and he invited me to a meal at his favorite Korean restaurant in town (or rather, one of Santa Barbara’s few Chinese restaurants, but one that happened to serve Korean dishes on the side). It turned out he had something more on his mind than introducing me to the food of his homeland. “I have a question to ask you,” he said after ordering, and nothing I could have considered in that moment would have prepared me for what came out next: “What is the American dream?”

I recall mumbling an unconvincing answer about small businesses, big houses, two-car garages, and green lawns — or at least I found it unconvincing myself, having ceased dreaming about suburban comforts the moment I realized alternatives existed. But clearly this teenager from a small city in South Korea, abroad for a none-too-intensive few semesters of community college in a California beach town, considered the definition of the American dream a much more urgent matter. A decade later, I wonder if, in the impressionable years of childhood, he’d ever watched LA Arirang (LA 아리랑), a mid-1990s family sitcom essentially all about the Korean vision of the American dream, small businesses, big house, two-car garage, green lawn and all.

If you’ve ever attended a Korean choral performance, you’ve almost certainly heard “Arirang,” the old folk song anointed by UNESCO as a piece of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and generally regarded as the unofficial anthem of the Korean peninsula. It comes in many regional variations, most from the different parts of the countryside and at least one from Seoul, and so it makes for a sufficiently clever joke to suggest, in the title of a show set in the city with the highest Korean population outside Korea itself, that the time might have come for “Jeongseon Arirang,” “Jindo Arirang,” “Miryang Arirang,” and all the others to make room in the canon for an “LA Arirang.”

Not that LA Arirang actually comes up with one, instead opting for for “From Now Until Eternity” (이제부터 영원까지), a song written, composed, and recorded by the real Korean lawyer who emigrated to America in the early 1980s and whose life in Beverly Hills provided a basis for the show. It does feel much more as if it might belong in American sitcom from that era than would even the loosest interpretation of “Arirang,” in line with every other element of the production: the laugh track, the living room set, characters’ big entrances from the nonexistent “outside” or “upstairs,” the saxophone-heavy soundtrack, the 21 minutes of gags that culminate in lightly moralistic conclusions. The result not only transposes the sitcom template into a Korean context, but exhibits a rare union of form and substance in so doing, painstakingly emulating the conventions of its American inspirations as it depicts a Korean family trying to adapt to the conventions of American life.

LA Arirang also broke new ground by daring to provide a lighthearted view of Korean immigrant life, whereas previous domestic works of film and television like Western Avenue, the pained study of Los Angeles’ 1992 riots that had opened two years earlier earlier, wallowed in the negative: cultural isolation, economic trouble, familial disappointment, discrimination, violence. But Kim, the attorney patriarch of the series’ central family, seems to have achieved the American dream and then some, having managed to house his wife, his two sons and a daughter, and even his mother on a tree-lined suburban street that, while perhaps not quite as dreamy Beverly Hills — and in actuality probably located in the suburbs near Gimpo Airport, where the show faked most of its “Los Angeles” exteriors — certainly reads, or read then, as American.

While some episodes do contain scenes shot in recognizable Los Angeles locations such as Griffith Observatory, LA Arirang‘s core concept doesn’t really necessitate them, set as it is less in the real Los Angeles than in an idea of Los Angeles entertained on the other side of the Pacific. A broad sense of place, or reminder of place, comes delivered by brief on-location shots of rollerbladers, sailboats, and drives down Wilshire Boulevard, shuffled and reshuffled between each commercial break and the scenes of the actual story, almost all of which usually plays out indoors: in the Kim family home, in Kim’s law office downtown, in the uncle’s Korean video store (complete with hand-labeled VHS tapes of Korean television dramas), in the control room of the local Korean radio station.

Not only could most episodes be shot in Seoul, they might as well have taken place there, especially since — and this could qualify as either an unrealistic representation of Korean life in Los Angeles or a highly realistic one — non-Korean faces almost never in the frame, apart from those of the occasional drunken white lummox or blonde slattern intent on corrupting the teenagers of the house. And so we have the only one of LA Arirang‘s themes that really springs from its setting: the generational-cultural gap between the immigrant parents and grandparents on one side and the Americanized children on the other (to say nothing of the gaps between the grudging grandparents and the more gung-ho parents, or between the children born in America and those just raised there). The former usually end up frowning sternly but benevolently at the latter, with their baggy, unflattering clothes, their informal manners, and their compulsions to go out to movies or sporting events.

LA Arirang‘s then-uncommon ability to play to more than one generation of viewers at once, and the freshness of its format, brought it considerable popularity and acclaim not long after its debut on the still-new SBS television network in the summer of 1995. Just months before, the American sitcom factory’s own attempt to essay these same themes had, coincidentally, come to an undignified end. More crudely and to a much cooler reception, ABC’s All-American Girl centered around a Korean family in San Francisco (with a small business selling books, though they branch out to renting out videos in the pilot), and more so its mildly rebellious daughter played by the comedian Margaret Cho and her ongoing struggle with her mildly traditional parents.

“The most incredible thing about the series is that it even exists,” the Los Angeles Times‘ Philip W. Chung observed about All-American Girl, though everything else about it could have sent entire Asian-American Studies departments into apoplexy even then. Take, for instance, the casting, a process that somehow managed to come up with no Korean actors other than Cho herself, resulting in not just a variety of farcical accents in English but near-unintelligibly delivered snatches of Korean dialogue as well. Then again, LA Arirang does little more convincingly on that score: if not for the Korean-language subtitles translating the lines of English sprinkled here and there for local flavor, I’d have no idea what most of the supposedly Westernized youngsters in the cast were trying to say.

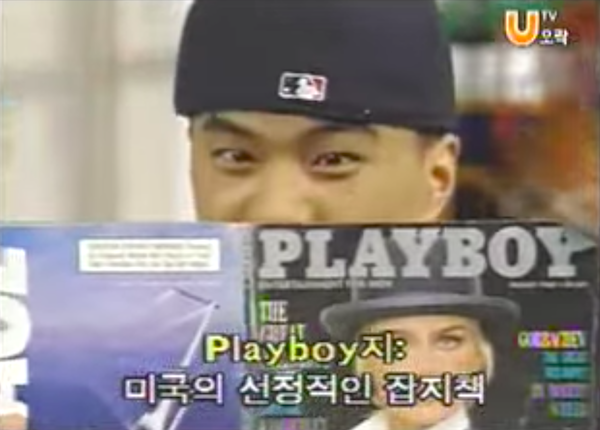

Even the English I can make out, I can’t say I buy, as when Kim’s oldest son, having successfully asked a girl out, clenches his fist in victory and shouts, “I can do! I am genius!” Yet I do appreciate something about the straightforwardness: watching either LA Arirang or All-American Girl, one gets the sense of the 1990s in America as a very different time indeed, closer in professed sensibilities to the 1950s than to those of the 2010s. One episode of the former finds Kim’s youngest son sneaking an issue of Playboy (“America’s lascivious magazine,” explains a subtitle) up to his room and gazing upon it with now-implausible titillation; the latter, while it allowed Cho’s character a certain obnoxiousness, clearly never drew as it claimed to from her much more rough-hewn stand-up act.

Korea, for its part, remains in the middle of what I’ve heard described as its own “long fifties” of transition between a culture of traditional values and martial virtues to something altogether more nebulous and permissive. This era had already begun by the time of LA Arirang‘s premiere, and indeed, some aspects of the series seem to date from America’s own loosely defined cultural “fifties,” especially the uncle who runs the video store. Any Westerner would read each and every one of his mannerisms (also characteristic of the actor himself, who has a parallel career as a TV chef) as a thinly veiled indication of homosexuality — the classic “confirmed bachelor uncle” of a bygone era — but for the fact that the show also sets him up with a wife and teenage daughter. Is he meant to be that deeply closeted, no doubt the condition of many gay Korean men of his generation? Or is he merely a cargo-cultish replication of what Korean viewers recognized as nothing more that a particularly funny character type from American sitcoms?

Yet for all its goofy earnestness, LA Arirang (a fair few clips and full episodes of which have surfaced, albeit in Korean only, on Youtube) somehow doesn’t feel as dated today as All-American Girl and its sneering protagonist. Observers of Asian-American culture have spent the past 20 years tearing the latter apart, and they seem to have inflicted the same degree of scrutiny upon Fresh Off the Boat, ABC’s more recent comedic venture into the Chinese pursuit of the American dream in mid-1990s Florida. North of the border, the CBC last year came up with Kim’s Convenience, a lower-profile but seemingly more respectable sitcom about at Korean immigrant life in Toronto that at least managed to scrape together a majority (or plurality, anyway) of genuinely Korean performers. But even after all these years, it’s LA Arirang that retains the ability to shock, and it does so by showing something that, no matter how many times I see it, I still can’t believe my eyes: the Kim family wears shoes inside the house. Now that’s pushing the boundaries.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Western Avenue: How Korean Cinema Portrayed the 1992 Los Angeles Riots

Watching Korea Develop through Sixty Years of Commercials

Multicultural Love and Its Discontents

A Korean Travel Writer Reveals the Los Angeles Even Angelenos Don’t Know

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.