The LARB Korea Blog is currently featuring selections from The Explorer’s History of Korean Fiction in Translation, Charles Montgomery’s book-in-progress that attempts to provide a concise history, and understanding, of Korean literature as represented in translation. You can find links to previous selections at the end of the post.

Because of the strong emphasis on oral tradition and poetry as literature, classical Korean written literature is rare. While the oral and poetic traditions date back to the Silla period, classical written fiction appears relatively late in the Joseon Dynasty. There are a few written records predating the twelfth century, so we can date the start of Korean classical prose from this time.

Korean prose began with historical records, notably the History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk Sagi), the collection of which was orchestrated by Goryeo’s King Injong (1122-1146). Another work of note was created by Buddhists: the Tripitaka Koreana collects the Buddhist scriptures in the form of woodblock carvings. Finally, the Samguk Yusa collects legends, biographies, anecdotes, and folktales from a variety of sources and across multiple dynasties.

Korean novels of all eras have a slightly different look and feel than in the west, as the form of the Korean novel (the sosol) includes short stories, novellas, and novels. The differences in length can be quite dramatic. Some “novels” clock in under 40 pages; Park Min-gyu’s brilliant Dinner with Buffett is an excellent example of this, scarcely clocking in at 30 pages in its English, but nonetheless published as an individual work in translation.

Other novels are produced in massive multi-volume collections, such as Park Kyung-ni’s sixteen-volume Land, still only partially translated into English. Some critics speculate that the Korean focus on, and even reverence for the short story reflects of the original Korean preference for oral poetry, many forms of which were quite short, pansori obviously excluded.

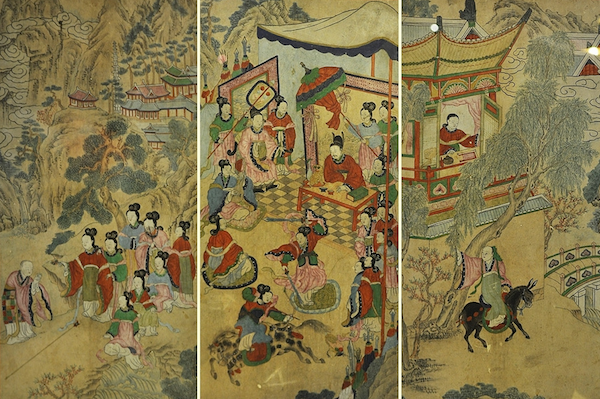

Classic literature began with the Tales of Kumo (Kumo Shinwa, or “New Stories from the Golden Turtle”) by Kim Shi-sup in the mid-fifteenth century and The Tale Of Hong Gildong, attributed to Hyo Kyun, in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. Indicating the language split that still existed in Korean literature at that time, Tales of Kumo was written in Chinese while The Tale of Hong Gildong was written, or at least recorded, in the hangul alphabet. Not surprisingly, the latter work has had more of a lasting impact on Korea.

In fact, Hong Gildong looms so large in Korean literary history that it deserves a closer look. After years of only being easily available in children’s-story versions, this Korean classic of family betrayal, adventure and eventually a kind of reunion is now in reprint and available on Amazon. It explores the socially inferior position of children born to the scholarly aristocrats known as yangban and the female entertainers known as kisaeng. Hong Gildong himself is something like the Korean Robin Hood, his story lampoons some of the absurdities of the life and social structure of the time. Despite this judgmental edge, it remains a very traditional work whose protagonist only to be reunited with his family and advanced in social position.

As the extremely talented illegitimate son of a government functionary whose own father is persuaded that he should be killed, Hong Gildong cannot find a place in Korea’s formal society of the time. Consequently, he runs away and becomes an outlaw who battles evil, murderers, and the government, eventually creating his own kingdom and demonstrating high levels of filial piety despite his circumstances.

Hong Gildong is so popular that it has been a staple of Korean culture since its publication, “translated” into video, television, related novels (such as Seo Hajin’s Hong Gildong), children’s stories, comic books, and even a musical. Hong Gildong also lies, as you read this, in the morgues of Korea, for in Korea the name “Hong Gildong” functions similarly to the name “John Doe” in English, a temporary name given to the unidentifiable corpses.

Other literary works began to move away from the tightly biographical, meditative, and philosophical, and to deal directly with Korean social conditions. An entirely new form of fiction called “family soap opera” also appeared around this time, telling stories covering multiple generations in a way still popular in Korea, a tradition that now includes works from Three Generations in 1931 to Please Look After Mom in 2009.

Many of these works, known as taeha sosòl (“great-river fiction”), were serialized, and thus began to extend the range of settings, characters and narratives of the fiction, thus removing some of the solipsism that had previously characterized Korean fiction. Because of their length, however, they are not particularly amenable to translation: Three Generations, for instance, was serialized in the Chosun Ilbo, not entirely published in even Korean until the 1950s and finally arrived in English translation at the alarming length of 432 pages.

From the seventeenth century on, written literature became more popular and a larger reading public emerged. As commercial publishing developed in Korea, book rental operations did brisk business. Subject matter expanded to include attacks on, and ridicule of, current social problems. As the parable-based nature of fiction decreased, the potential cast of characters and topics increased: characters of “lower” social status — merchants, criminals, and even kisaeng — began to populate literature.

These diversions were no doubt hastened, or at least accompanied, by an increasingly large number of works composed in hangul. While The Story of Hong Gildong is the most notable, these also included Lady Sa’s Southward Journey in the eighteenth century and Kim Man-jung’s The Cloud Dream of the Nine in the seventeenth, both widely read by women and common men. Other fictions of the late Joseon Dynasty were concerned with proceedings of the court, including Record of Leisurely Feelings (1795-1895) and Queen Inhyon’s Story. As these works were being written, hangul itself spread throughout society, beginning at the bottom and working its way up.

The Cloud Dream of the Nine by Kim Manjung, also available on Amazon, is an early novel of competing ambition and faith as well as a love story. Putatively the tale of a youth traversing two different lives in the company of eight maidens, it was written in the Tang Dynasty and explores the competition at the time between the religion of Buddhism and the ethical system of Confucianism. These the two main pillars of Korean philosophy often found themselves in opposition. Author Kim Manjung wrote wrote seminal work (translated by James Garth Scale in 1922 and re-issued in 2003) while on the road in exile, supposedly to distract his understandably upset mother. It went on to become a Korean classic in part, like Hong Gildong, because it was translated into hangul (the original language quite clearly being Chinese, an issue which causes some critics pain in calling it part of “Korean” literature).

Unfortunately, the true extent of the classic novel may never be completely known, as most of them did not survive their own era. Scholar Kim Hunggyu notes the one-time existence of some six hundred classic novels: heroic novels, fantasy dream novels, historical war novels, pansori novels, family novels, and novels still in classical Chinese. Hong Gildong resides, of course, among the “hero” novels, and The Cloud Dream of the Nine among the dream variety. Pansori novels included the Tale of Ch’unhyang, the Tale of Shim Cheong, and the Tale of Hungbu. That last has lived on in various forms, including as the children’s book On Hungbu and Nolbu, as a drama and theater, and even on a set of stamps released in 1969 and 1970.

As the Classical Era wound down with the weakening of the Joseon Dynasty and a brief “Enlightenment” began, ideological and physical forces marshaled themselves to invade Korea as the groundwork for Korean modern literature was being laid. The land, so to speak was being prepared, both psychologically and technologically, and soon political realities were to intervene in unexpected and distorting ways.

Related Korea Blog posts:

How Did Korea Get Fiction in the First Place?

Where is Korean Translated Literature?

What Shaped Translated Korean Literature?

Why Does Korean Literature Use an Alphabet?