When I think of my favorite travelers to read, I think mostly of Brits: Jan Morris, from Wales; Colin Thubron, from London; Pico Iyer, born in Oxford to an Indian family and raised part-time in California. But none of them, however much I wish they would, have written at length on South Korea. In the peripatetic late chapters of her life after more or less quitting England, Isabella Bird Bishop alighted in Korea and produced a book still read by Korea enthusiasts today, though she did it back in the 1890s. The very well-known Simon Winchester and the less well-known Clive Leatherdale did get out here more recently — but by “more recently,” I mean the 1980s.

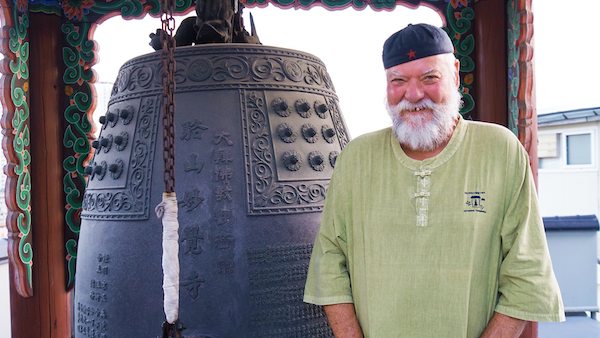

So it made for a relatively important new chapter in the history of British visitors to Korea when Roger Law arrived this year to put together Art and Seoul, a five-part series for BBC Radio 4. Law, whose name may not ring a bell to non-British readers, began his career as a caricaturist in the 1960s, going on in the 1980s to co-create the popular satirical puppet show (yes, really) Splitting Image. The show’s end in 1996, and thus the end of the arduous work of public figure-lampooning puppetcraft it demanded, gave Law a chance to pursue a new artistic dream: studying ceramics in China.

At some point in this East-oriented period of his life, Law took a glance over at the work of his neighbors on the peninsula and found himself captivated by the moon jar, in his words “a misshapen round pot, and it looks so simple — but it’s not. To me, it’s the very essence of the Korean soul.” He sets what he sees as this “quintessentially Korean” object against the “pretty flashy” pottery of China where “everything has to be perfect — perfect” and the “artsy-fartsy” pottery of Japan. “Korean pottery has a simplicity, an earthiness about it,” he observes, “that seems to me to be very Korean.”

This realization gave Law that most useful possession of the Westerner in Korea, a straight answer to the question of what got them interested in the country. He can just say the pottery, while others can say the music, the movies, the television dramas, the food; I usually give the slightly more complicated answer of the language, inextricably tied up as it is with so much else. But those of us who decamp for Asia can usually point to one element above all that fascinated us enough to motivate us to do so. And when we get here, we face a big question: does the piece of the culture for which we originally fell represent the culture as a whole? In Law’s case, will all of South Korea possess the same captivating simplicity and earthiness as the moon jar?

Yes and, inevitably, no. The series’ first episode does find Law beholding the very human and often faintly strange beauty of Korean artist-craftsmanship, manifest in pottery and otherwise (he also visits artists working with such different materials as the mulberry-paper pages of old-fashioned school textbooks), but also grappling with one of the machines the subway to get it to dispense a T-Money card (“their version of an Oyster card”). It startled me to suddenly hear their recorded commands, a sonic fixture of my daily life here, broadcast from an island on the other side of the continent, but where they hit me with a shot of unexpected familiarity, they hit poor Law with a shot of bewilderment. “The machines only really deal in Korean,” Law speaks into his recorder, “and, uh… I have no Korean.”

He goes on to seek help, in vain, from one of the subway’s volunteer “old-age pensioners, even more old and confused with technology than I am,” with whom “you can spend hours jabbering away, they in Korean, you in English, getting more and more confused.” In this and other respects, he places himself in the role of the bumbler (albeit an intelligent bumbler) abroad, one that, with his self-deprecating jokester personality and the sense of adventure just underlying his grumbling, he plays wholeheartedly, making bits out of such minor struggles as his inability to pronounce so much as a Korean name. Only Brits can really pull this off; an American trying it just looks like more of a yokel than usual. (And it doesn’t suit every Brit. When Thubron goes to China, for instance, he sits down and learns Mandarin, a task I suspect many a British traveler of his and Law’s generation would consider an indignity.)

Law’s quest to gaze upon the true nature of Korean ceramics soon leads him down several standard paths for the observer of 21st-century Korea: the “nightmare” education culture; the robust plastic surgery industry (“I can’t tell the difference between the before and after,” he rightly observes); the temple stay (“there’s an awful lot of shoes-off, shoes on with this Buddhist business”); the taste of “the national dish, kimchi” (the popping sounds of whose fermentation, which I myself had never heard before, he gets on tape); and the vanishing culture of the haenyeo (해녀), the strong-willed and inexorably aging lady divers of Jeju island.

But in his time on Jeju, Law also visits such nonstandard institutions as the local teddy bear museum (“I hate to admit it, but I’m actually enjoying this”), and in his exploration of the unignorable Korean film industry, he chats with critic Tony Rayns (long a beater of the drum for the better Korean cinema) in Chungmuro, the former “Hollywood of Korea.” The directors, screenwriters, and producers have long since vacated it, but it remains one of Seoul’s mostly unacknowledged fascinating neighborhoods. And at least he doesn’t make the obligatory trip north to the Demilitarized Zone, to return the grim stares of the North Korean border guards and ponder aloud the inscrutable menace of the Hermit Kingdom.

Having enjoyed Art and Seoul — and wishing I could hear more broadcasts like it, about Korea or anywhere else — I come out of it still wondering to what extent the moon jars Law loves so much reflect the entirety of Korean culture. On one level — the most visible level here in Seoul — Korea looks like doing its level best to de-simplify and sophisticate the earthiness out of itself. But lamenting this sort of thing can border on poverty fetishism; to hear some Westerners tell it, Korea hasn’t been itself since its first skyscraper topped out, a line of thinking that rolls you down the slippery slope toward denouncing indoor plumbing. But the distinctive “rustic flair” of Korea, as I once heard it described, does exist, and it does bring something important to the table that those drawn to the country and its culture don’t feel in China or Japan.

I personally find Korea’s enduring mixture of modernity and everything else the exciting thing, and Law’s radio journey provides an entertaining overview of just that: the high-tech subway and its low-tech volunteers; the new cultural institutions springing up left and right, all of them with their occasional rough edges and bits of eccentric content; the much-promoted vacation spot dotted with phallic garden gnomes; the trendy cuisine that still uses blocks of Spam. “It’s not looked down upon here,” Law says of that infamous canned meat, inadvertently highlighting the wide streak of earnestness giving all this its appeal: “You don’t have any Korean pythons singing about it.”

You can listen to all the episodes of Art and Seoul at the BBC’s web site.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.