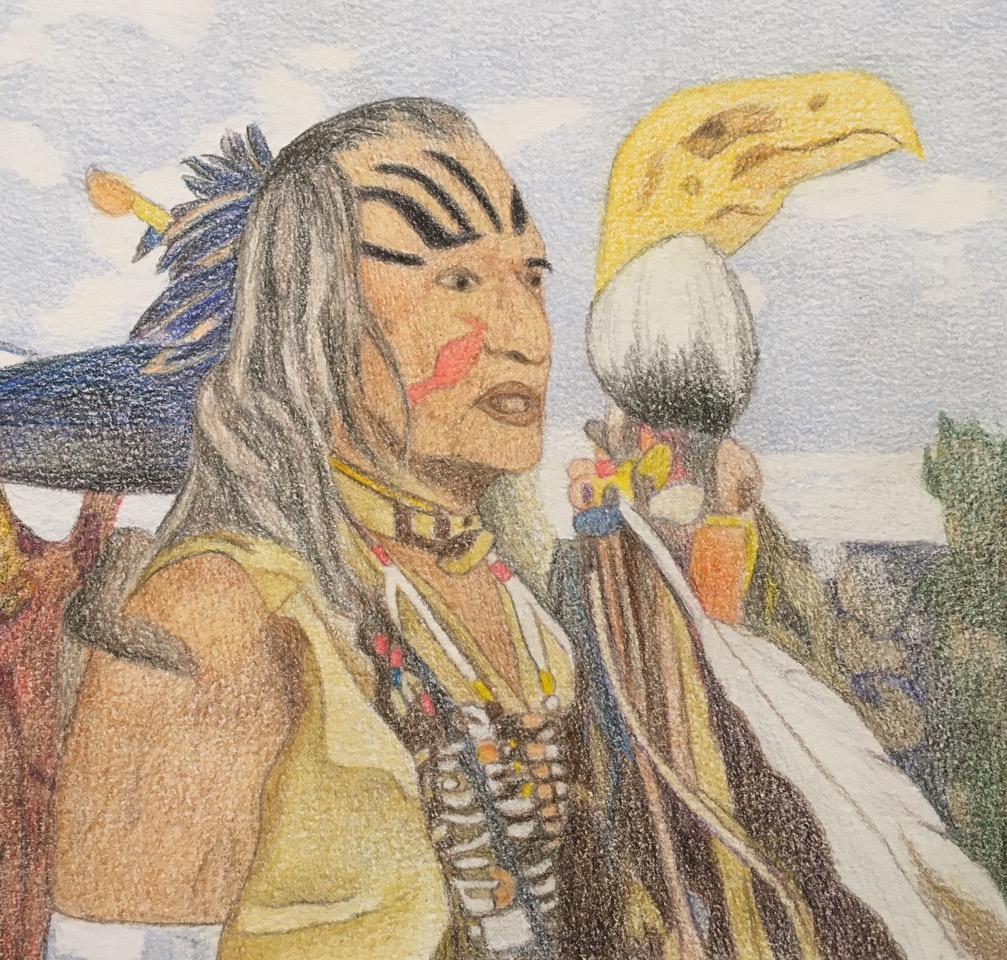

The following article is the second in a five-part series about the movement at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The mobilization, of people and resources, which was spurred on by the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, began an unprecedented convergence of hundreds of Indigenous Tribes, and thousands upon thousands of people. The series, which was originally written as a single piece, offers the reflections of Brendan Clarke, who traveled to Standing Rock from November 19th through December 9th to join in the protection of water, sacred sites, and Indigenous sovereignty. As part of this journey, which was supported by and taken on behalf of many members of his community, Brendan served in many different roles at the camps, ranging from direct action to cleaning dishes and constructing insulated floors. He, along with the small group he traveled with, also created a long-term response fund, which they are currently stewarding. These stories are part of his give-away, his lessons learned, and his gratitude, for his time on the ground.

ARRIVAL

The journey to Standing Rock was relatively smooth, all things considered. These considerations included a 22-year old truck, a lightweight trailer, vehicle electric hook-up complications, several thousand pounds of supplies, and three drivers with little or no experience towing any trailer whatsoever. They also included a Sierra Nevada snowstorm, an early morning scramble for tire chains, and mile after mile of driving this wide-backed continent called Turtle Island. With speed limits upward of 70 mph on many of the interstate highways in the Midwest, and a maximum towing speed of 55 mph with our rig, we perhaps were considered a kind of turtle in our own right. Nevertheless, slow and steady, we arrived safely on November 22nd.

We arrived to a camp in expansion and recovery. The expansion was from the thousands of people on Thanksgiving break who decided to come to camp. The recovery was from the events on the evening of Sunday, November 20th. As far as I know, this was the first night wherein the law enforcement protecting DAPL turned truck-mounted water cannons — a weapon that first came on the scene in 1930s Germany — against the water protectors. This alone would have been sad enough — turning the very thing that the camps were trying to protect into a weapon against them. What is worse though, is that the spraying took place in the evening, in sub-zero temperatures, which increases the risk of hypothermia and freezing injuries significantly, thereby turning what might otherwise be deemed a “non-lethal” weapon, into a potentially deadly one. According to medical reports, 26 people were hospitalized from the use of force, and more than 300 were injured. These injuries included bone fractures, and for one woman, the loss of her arm. Put simply, people were shaken up.

The wake of this night of mass injury was the field into which we arrived. Even while on the road, the closer we got to Standing Rock, the the seriousness of the risk that we were moving toward became more apparent. It was in part this contrast, between the field of fear surrounding the camps, and the generally peaceful atmosphere of the camps themselves, that was so surprising.

GETTING ORIENTED TO LIFE ON THE GROUND

Having landed at Rosebud, we attended the mandatory orientation meeting the following morning. These meetings were run by non-natives, who had been asked by the indigenous elders to deliver certain messages. The size of these meetings swelled into the hundreds during the Thanksgiving break, as thousands of people poured in from around the country. The camp itself expanded to an estimated 14,000 people.

The meeting began with the facilitators introducing themselves as non-native: one Filipino, and the other white. They asked if there was an Indigenous person who wanted to offer an opening prayer. Everyone removed their hats, as was customary with prayer.

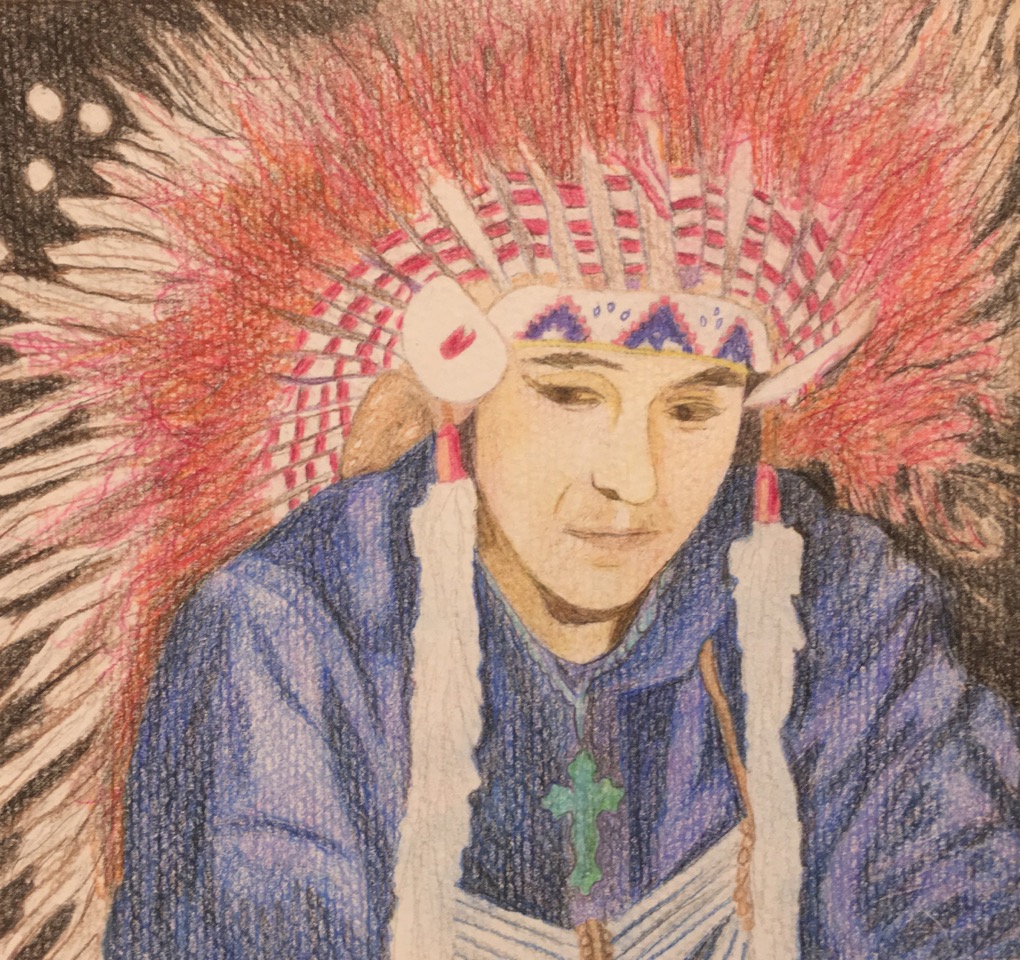

We then heard something of the context, and the privilege to be welcomed into the historic moment. There were four central messages: 1) This movement is Indigenous-centered; 2) This is a peaceful prayer camp; 3) Be of use; 4) Bring it home. As the white female facilitator from Oakland outlined protocol regarding camp culture, she created space for Indigenous People who wanted to add from their knowledge about Native culture. A fire-keeper from the Hoopa tribe in California offered his wisdom about fire, anger, and the need for non-violence; a clan mother from British Columbia sang a blessing song for water; others chimed in about moon lodge culture, and more.

The facilitator also spoke about cultural “whiteness,” and some of the cultural norms amongst European-Americans that can be deeply disrespectful to others. Then came the moment for questions from the audience. Rather than open it up for anyone, the facilitator did what I later saw used again and again as part of the “official” camp protocol. She created three rounds of questions. The first was for Indigenous People, the second for people of color, and the third for anyone else. Now, this is not a perfect structure. It is rooted in static categories bound to historical legacies that rarely account for identities, which themselves may be fluid, intersecting, and complex. Nevertheless, what happened in that moment was beautiful. A new structure arose, which directly addressed some of the structural oppression and racism that has been, in most cases, literally the law of the land, for hundreds of years. In essence, white people were asked to be quiet and listen, to give space for other voices. This structure was introduced with clarity and resolve, but without anger or disrespect.

This tactic, of a structural response to structural oppression and the legacy of colonialism and patriarchy, went further. For example, the medical tent in the main camp consisted of tents for herbalism, body-work, trauma, and more. This meant that Native Americans staying in this hastily-built camp were able to receive better healthcare than they normally might from Indian Health Services, which is consistently among the lowest-funded government healthcare projects.

In essence, this camp was founded on the principle of being for something, rather than against something. For instance, it was founded on being for the protection of water, not just against the construction of the pipeline. It was founded on being for Indigenous sovereignty, not just against white supremacy. In a sense, many decisions at camp were led by a guiding question: if the structures in place are not the ones we want, then what structures, if any, would we build to create a healed picture?

The next morning, Jiordi and I drove into Oceti Sakowin to unload supplies. We pulled into the main road, known as flag road. It is a road lined on either side by hundreds of flags representing the nations that had gathered in support. They were mostly flags of indigenous tribes — most of which I had never seen before — from sovereign nations that exist on the same land where one flag, with 50 stars, is said to represent the people of this place.

I said to Jiordi, “I feel like we are arriving at the United Nations, only it is better. The nations are actually united, and they are united around water.”

We pulled in a bit further and stopped as a Native woman met us at the security checkpoint. She walked right up to the truck window.

“New to camp or returning?” she asked. “Returning,” we replied, having checked in the day before. She looked at each of us for a short, powerful moment, and said, “Welcome home.”

THANKSGIVING AND THE STORY OF STUFF

For days on end, vehicle after vehicle came and unloaded people and stuff: clothes, food, tools, wood, shelters, and more. The colorful mountains of things began to rise against the backdrop of the brown hills, soon to be covered white with snow for the rest of the winter. A significant amount of energy was spent just to receive all of the donations, and these donations supplied some of the energy to keep camp running.

If the structure of capitalism is not sustainable, which I fervently believe it is not, then it begs the question, what structure would replace it? The answer that arose, although perhaps less by design than through a process of emergence, was a model of gift economy. No one in camp paid for food, water, medical services, legal advice, construction labor, or clothes. All was offered freely, and paid for by the currencies of generosity, reciprocity, and responsibility, which began well beyond the borders of the camp. While capitalism offers debt, by way of endless interest bearing growth, the gift economy offers “indebtedness” by virtue of relationship. The gift is rooted in and gives root to relationship. To live, consciously indebted, is to recognize that we only ever live from the generosity of life itself. What we owe in return is our gratitude, our care, and our responsibility, and the planet would likely benefit from more of each.

The beauty of this gift economy is for me, the takeaway. Nevertheless, despite the functioning gift economy and the generosity flowing toward camp, there were other layers of complexity to consider. The influx of stuff created at least a few unintended consequences. For one thing, the camp began to generate a significant amount of trash. As an otherwise unoccupied, mostly barren piece of land, the camps had no regular trash service, save the beaten-up old pick up truck spray-painted: “The Lost Boys,” which swung through camp every few days to load up bags of trash. It begs the question, how much stuff is enough, and from where and how will we source the energy to build a new culture?

Another side effect of the influx of stuff was the highlighting of a culture of disparity. In the United States, this is the norm: a tremendous gap between the rich and the poor. In a place of deep economic poverty such as Standing Rock, the larger dynamics of inequity found their way, albeit to a lesser degree, from the culture at large into the camps. There were those who had beautiful, new, heated dwellings, and those who did not. There were those who had the “right” clothing, and those who did not. And while for the most part, the folks in the camps found what they needed, the contrast between the outpouring of support to the camps, and the general overlooking of the poverty-stricken reservation stretching out next to it, was far from ideal. Things sometimes went missing at camp, and did not find their way back. While some of this was likely due to people using whatever they could find to make do, it is likely that some was due to theft. In one extreme example, a local resident stole and pawned four wood stoves from Rosebud. They were caught and arrested. While it seems reasonable that the person who stole ought to be held accountable for his or her actions, so too might we question what accountability lies on the society that allows some to live in extravagance, and others to live without basic needs.

HOLY-DAYS

After just two days in camp, it was Thanksgiving Day. In my life at home, Thanksgiving, as a “holy-day,” had become one of my favorites. Time with friends and family, good food, and a break from the buzz of ending autumn — what’s not to like? In college in Montreal, I even had the good fortune of doubling up on Canadian and American Thanksgivings.

But, despite its name, Thanksgiving rarely had much of anything to do with giving thanks. As an American holiday, it is also a centerpiece of the whitewashed mythology regarding colonization. It is the portrait of a happy meeting between Indians and pilgrims, each offering some great gift to the other: corn-planting techniques on the one hand, and turkey, tables, and civilization on the other. I was not particularly naïve, nor did I believe the mythology around Thanksgiving. But, in a world of broken cultures and centuries of disconnection from the land and waters that birthed and cradled my ancestors and their languages, any fragment of any picture at all, is sometimes easier to cling to than the more beautiful world we know is possible, or worse yet, don’t know is possible. When contrasted with a culture of thanksgiving, such as the Haudenosaunee — which has gifted the world the Thanksgiving Address, democracy, and the Great Law of Peace, among other cultural lifeways — setting aside one day out of the year to give thanks is a bit unbalanced, at best. All of this was swirling in me and in camp as I awoke on Thanksgiving Day. This day, however, would prove to be something altogether different than I have known.

The early morning prayers had ended, and as we gathered at our tents to figure out what to do for the day, we suddenly heard scratchy voices coming through walkie-talkies and saw security people running. Soon a truck came by with someone on a loudspeaker, making announcements. We headed over to the main dome at Oceti and found a large gathering of people. There was a general sense of alarm and uncertainty, and rumors were floating around that there was a police raid planned for the camp. The following message was being echoed out from the speaker at the center of the circle:

“Women with children to Rosebud. Men to the front lines. Women without children are free to choose where to be.”

Before arriving at camp, I had been grappling to find my relationship to direct action. This uncertainty was only exacerbated once I arrived at camp. The message of “No actions today,” would be competing with someone on a megaphone by the front entrance calling for people to gather for a direct action, or with actions led by the more militant Red Warrior camp, who had purportedly been asked several times by the elders to leave Oceti Sakowin. But in this instance, my decision came easily. If a raid were being planned for this camp, full of elders, women, and children, I would put my body on the line to protect it.

The front lines, although ever changing, centered mostly around Turtle Island, the name of a sacred site and burial ground to the Northeast of camp, and the bridge north of camp, on Highway 1806. This bridge, barricaded and guarded, was the clearest line between the camp and the law enforcement. It was this bridge where the water cannons were used. It was this bridge that placed people into opposing sides of the situation. This bridge, literally and metaphorically, is the one we were and still are collectively trying to find a good way across.

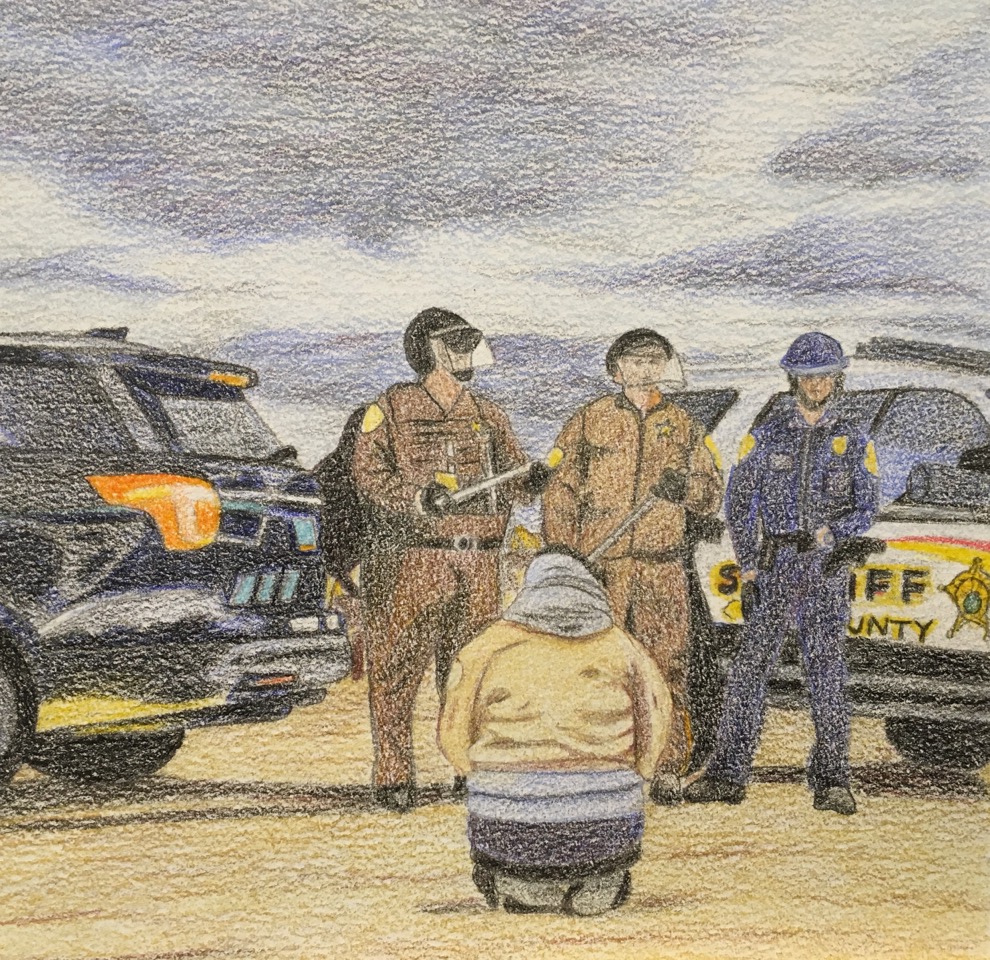

I was all set and ready to go out to the front lines when I remembered that I had on the necklace, gifted to me by a beloved Odawa teacher and elder in the nature connection community, and tucked into my many layers of shirts, sweaters, and jackets. He had given it to me to wear for protection while at Standing Rock. In that moment, I remembered too what they had told us about “sacreds” during the direct action training I attended on day two. Local police had been taking sacred items, after illegally strip-searching people, and either not returning them, or smashing them intentionally. This is, in many ways, akin to the bulldozing of sacred sites, or the desecration of places of worship. For those who carry the banner marked, “Defend the Sacred,” and who often place some of the power of ceremony and prayer in sacred objects, the willful destruction of these items is a cruel and indefensible act.

There was no time to make the walk back to Rosebud, and so I had to choose: do I wear this necklace, given to me for my own protection, and risk having this sacred- item-on-loan destroyed by some jailer, or do I hide it somewhere nearby, and add it to the list of sacreds to defend? I opted for the latter and tucked it into the rafters of the dome outside of which we had gathered. I wonder, having heard stories of hidden ceremonies that took place before the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978, and others even since then: how many Indigenous people have faced a similar dilemma over the centuries? What was left behind, when the Tsilagi, or Cherokee, were forced to march on the Trail of Tears, or when children were pulled away from their families and sent to the Carlisle school? And on what scale? Have the scales of justice tipped in their favor since then?

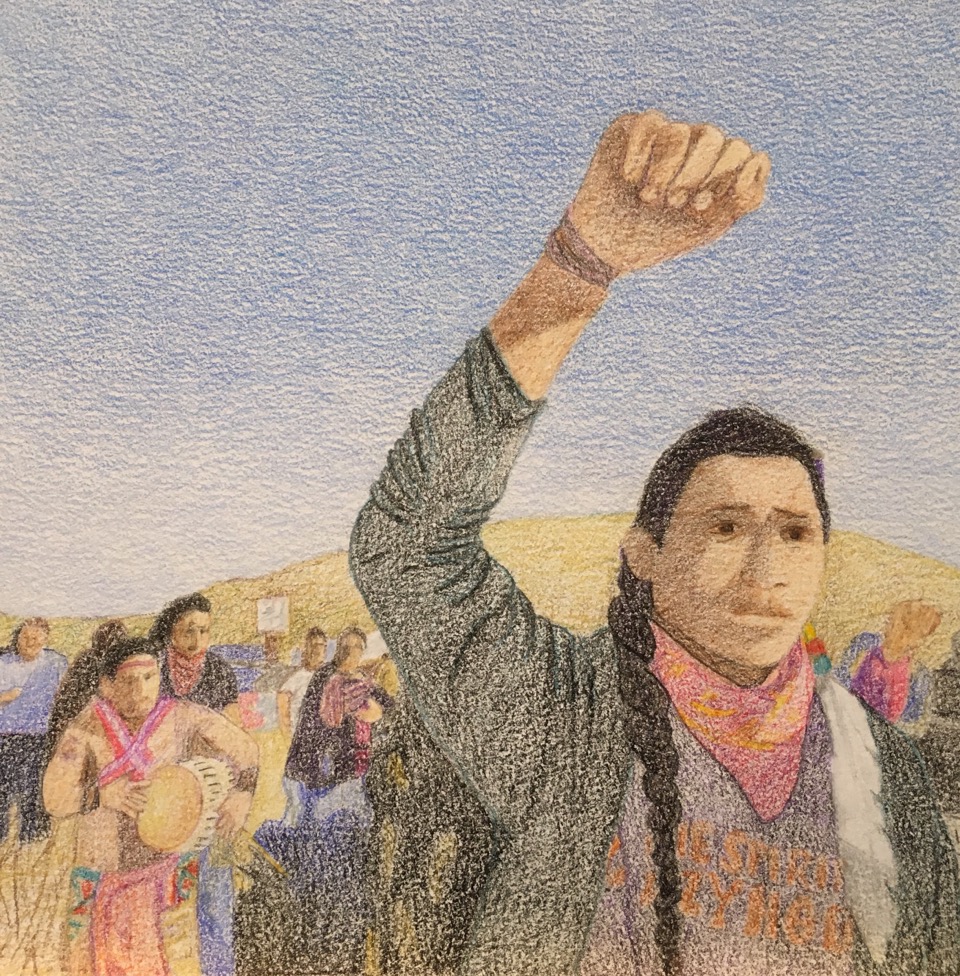

As we began marching toward the barricaded bridge, some were chanting, and others were walking in silence. The group walked slowly, at the urging of the leaders. My heart was beating fast and I could feel adrenaline course into my body as we stepped toward the unknown, well aware of the escalation of violence in the past days. Then, as if in answer to my whispered prayers for support, someone in the back of the march began singing a song. The lyrics of the song, as I first learned them, are:

Lay yourself down on the rocks now

Lay your body down, by the river

Listen for the drumming on the other side

Lose yourself in the meantime.

This song was birthed by a friend of mine, Meredith, along with a group, while we were on a wilderness trip in the Yolla Bolly Wilderness in California. We were camped on the banks of the Eel River, named for a now extinct endemic species of eel that used to inhabit its waters. The song, in its few short years, has morphed and changed, and traveled as far as Peru and across the United States. To hear it sung by total strangers, in this prayerful march toward militarized police, was to receive a blessing from the water of the Eel River itself. My whole body calmed. Although we were being watched by police day in and day out, so too were we being watched over.

We arrived at the southern end of this barricaded bridge and formed a large circle. Indigenous leaders offered prayers and songs into the circle. Later, others were invited to add to the offerings. A powerful, distant megaphone, being used by police on Turtle Island, began competing with the soft-spoken prayers. The amplified voice battered around in the low rolling hills, and made it hard to focus on the prayer. In the distance we could see a group of people at the base of the hill, and a small row of tiny black dots on the hilltop. What then ensued was like some dark comedy narrated by the police themselves. Like a teacher, powerless to stop a classroom full of unruly students, came the series of commands: do not attempt to cross the river. Do not attempt to build a bridge. Do not cross the bridge. Go back to the other side.

Police vehicles began speeding away from the barricade where we were standing and driving across the hills to reinforce the ridge of Turtle Island. Eventually, our group completed our prayers and marched back to camp to resupply, and then join the efforts on the ground at the base of Turtle Island.

We joined the group of water protectors, by then numbering in the thousands, standing and watching the row of 75 law enforcement officers and firefighters, armed with bottles of chemicals, bright orange guns, and riot gear. Using the technology of “mic check,” whereby the words of one speaker are echoed by a crowd to make them audible, a native elder delivered a message to the police:

To our relatives on top of the hill. Please remove yourselves from the hill. You are standing on the graves of our ancestors. It is a simple request . If you leave, we will go back across the river.

The sound of nearly 2000 voices saying anything in unison is not something I have experienced before, and its effects reside deep in my being. But even farther-reaching was the beauty of the message. In a country where the former commander in chief says confidently, “You are either with us or against us,” the concept of enemies is contagious. In a culture of fear, and subsequent security through control, the need for more sophisticated detection systems, alarms, and military capacity is the norm. But, in a culture of relationship, and a worldview of interdependence, the idea of an enemy does not hold water. Victory is not achieved when the oppressors themselves become oppressed. Otherwise, all that comes is the next cycle in a vicious circle, like the descendants of once-persecuted pilgrims becoming the ones breaking up groups of people praying and singing. To hear this Lakota elder, in a moment of such intensity, speak to the concept of relatives, was a humbling reminder of the power of forgiveness and peace.

It was a powerful reminder of relationship, woven into the very fabric of a culture. Ilarian Merculieff, an Unangan elder, expresses this idea in yet another simple, beautiful way. As he has explained many times, in the Unangan language, when people greet one another, they say, “Hello my other self.”

This standoff, of worldviews and people, continued for a time, and then, in yet another show of humility and graceful power, the water protectors, having not had their request met, headed back across the bridge anyways, and engaged in prayer. We formed one huge circle, the other side of which I could not see on account of the dips and ridges on the land, and the sheer size of the circle. The International Indigenous Youth Council entered the center of the circle. We all removed our hats.

“Pray with us!” yelled one person to the officers. “Circle up!” cried another. “Please take off your hats,” shouted a third. They stood there, immobile, a few engaging in conversations with their neighbors, and all of them looking visibly more relaxed. We prayed and sang, giving thanks for this day. Then, before we all began to disperse and make our way back to camp, a few water protectors turned and waved to the police. One single police officer waved back, in what was the first normal human response from the people wearing police uniforms in the entire daylong standoff. As I walked back to camp, I was reminded of the Christmas Truce in 1914, during World War I. Despite the refusal for a truce by the leaders of the opposing forces, the everyday people in the trenches took matters into their own hands. Soldiers put down their weapons and risked their lives by walking into no-man’s land, calling “Merry Christmas” in the language of their “enemy.” After the fear of some devious trick abated, the soldiers from the other trenches reciprocated. People shared cigarettes, food, Christmas carols, and even a game of soccer, on the battlefield of World War I.

I am brought to tears nearly every time that I think of this moment, of how much has been lost, not due to malice and greed, but to the failure of imagination of a different way, and the courage to see it through. On this year’s Thanksgiving, perhaps that single wave back, is the harbinger of more courageous imagining, and a more peaceful horizon.