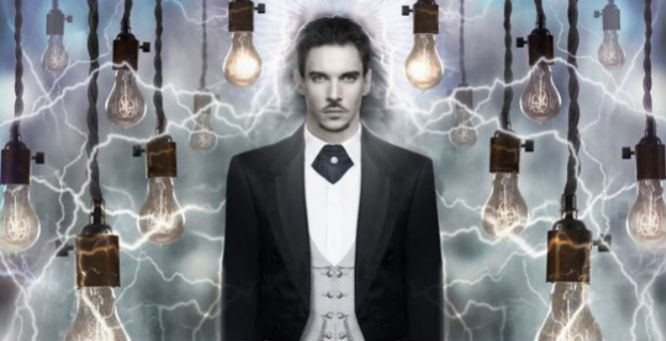

SCIENCE FICTION television this season continues to work through the anxieties of our contemporary moment in coded ways, from Revolution’s staging of another civil war in the battle between the “patriots” and the United States (although, confusingly, these patriots are those opposed to the ethos enacted by the Patriot Act); to Arrow’s defense of the 99% against the 1% (that, sadly, as I anticipated, has villainized the Latino mayoral candidate and seems to be becoming an apologia for the rich who apparently really do have the best interests for all in mind); to Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.’s internal battle as it tries to reconcile its countercultural sensibilities with its series premise as agents of a secret, military government agency (the most tiresome of these literalized metaphors, with yet another story of on-again, off-again Skye loyalty); and finally to Sleepy Hollow’s reinvention of the Revolutionary War as Armageddon. Yet the most interesting sf television recently was the debut of the new NBC Dracula series – that reinvents Dracula as a science-fictional, steampunk hero, played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers, famed for his portrayal of Henry VIII on The Tudors (2007-2010). Finally we have a television series that takes vampires out of high school and puts them back in the 19th century, where they belong.

Steampunk, for those not in the know, is a science fiction subgenre and emergent DIY culture based on a reinvented version of the Victorian era. Steampunk is so-named because its earliest iteration in the early 1990s grew out of then-dominant cyberpunk fiction. Cyberpunk was a dark, noirish subgenre exploring emergent IT culture set in a dystopian future of massive urbanization, corporate rule, and the disposal and fragile human bodies. Steampunk lightened this dismal view with some Victorian technological optimism, and in one of its earliest examples, The Difference Engine (1980), written by cyberpunk writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, imagined an alternative Victorian era in which Charles Babbage succeeded in developing a functional computer, the analytical engine in contemporary parlance. Thematically steampunk focuses on reimagining the past so that it results in a different future, and it steers a careful path between the dystopian nihilism of cyberpunk’s vision of technology displacing humans and an equally dire anti-technological determinism that sees such oppression as the inevitable outcome of technological change. Aesthetically, steampunk has developed as a DIY culture of costumes and object making, its fan conventions serving as a site to admire the innovations of computers whose functioning is made visible in ornate brass fixtures or the costumes that evoke a romanticized version of 19th century attention to detail and ostentatious display. Steampunk celebrates the lush beauty of Victorian-era design, and attendees appear in the dress of imperialists with all the attendant pomp and excess. While not overtly racist, steampunk culture for the most part ignores the destructive colonialist activity of the Britain it invokes, although it also can serve as an imaginative resource for colonized nations to equally imagine their histories otherwise via different technological development, and to assert a critical perspective on the Western narrative of “progress.”

Which brings us to the reinvented steampunk Dracula. Bram Stoker’s original novel, published in 1897, was deeply immersed in contemporary Victorian anxieties about the threat of the exotic others from the vast empire coming home to the imperial center of London. Dracula infiltrates the highest echelons of London society and embodies the threat of miscegenation in the contagion he can spread through his blood and in the sexual power he holds over supposedly chaste women who “belong” to his male antagonists. Imperial expansion is both power and vulnerability for Stoker’s Britain – recall that it is a real estate transaction that lures Jonathan Harker away from his fiancée Mina and into the dark Carpathian Mountains that are Dracula’s home. In Stoker’s novel, upper-class men banding together are able to expel the foreign threat, destroy the contaminated women, and purify Mina of her tainted sexual bond to Dracula, restoring her to proper wifely virtue and motherhood. NBC’s new series resituates this tale in an intriguing steampunk fashion: Dracula is now the good guy, teamed up (albeit secretly) with Van Helsing, and he plans to defeat the evil, imperialist Order of the Dragon (represented by the wealthy upper-class of London) by undermining their economic base in oil with his new electrical power source rooted in geomagnetic technology. In this series, far from banding together in class solidarity to repeal foreigners, the white men of the Order of the Dragon actually created Dracula by punishing Vlad Tepes for disobedience with a cure for immorality, potentially a metaphor for the “chickens” of colonialist exploitation coming home to roost. Thus NBC brings us a steampunk Dracula for the 21st century, a reorienting of steampunk’s technological fascination away from computers and toward technologies of energy – key to the looming end of industrial life-as-we-know-it.

The Order of the Dragon is some combination of corrupt, rich industrialists and religious fanatics along the lines of the Inquisition. Both Dracula, as Vlad the Impaler, and Van Helsing have lost wives who were burned at the stake by the Order: in Dracula’s case, his wife Illona is a doppelganger for Mina Murray (Jessica de Gouw), which also introduces a love triangle that might prove tedious as the season continues, but which is intriguingly complicated by the addition of Lucy Westenra’s (Katie McGrath) attraction to Mina as well. Renfield is no longer a hapless insane asylum inmate victimized by Dracula as in the novel, but now a trusted employee and confidant, played by Nonso Anozie who is thus far the only person of color in the main cast. Dracula infiltrates London society disguised as an American industrialist, Alexander Grayson, which enables the series to comment not only on shifts from IT to oil technologies, but also from British to American empires as the site of anxiety over the past 100 years. Whether this vision of a predatory British empire now long passed will be used to exonerate a contemporary American economic empire as the series continues remains to be seen. These dual identities also allow Rhys Meyers to switch between his British accent, perfected as Henry VIII, and the American one we saw on display in his feature film From Paris with Love (2010), demonstrating his charms in both registers to full effect. Denouncing the Order of the Dragon to Renfield, he castigates them as recognizable by their “overtly grotesque sense of entitlement” and announces that they have moved on from inquisitions and public burnings to “business via private clubs and boardrooms.” The Order’s obsession with oil and politics, he proclaims, emerges from a belief that “it will fuel the next century, and if they control it they will control the future.” By subverting the economy to another power source, he believes he can defeat them.

Dracula is thus positioned to use steampunk’s techniques of critically reinventing history to comment on the last century of industrialization via oil, on our looming ecological and energy crisis, and even perhaps on the class exclusions of both the Victorian era and our own, suggested by Dracula’s rant against entitlement. The series promises a rebooted 21st century built on something other than oil and imperialism, an intriguing thought experiment. And of course it also brings all the hypnotic and sexual appeal of the vampire genre, but without the sanitized blood-bag drinking teen vampires that have recently dominated the vampire tale. Rhys Meyer’s Dracula may be fighting the good fight against imperialists, but he also uses his considerable charisma both to manipulate as Grayson and to lure other female prey – whose blood he drinks directly from the neck, as all real vampires should. This Dracula embodies all the sinister yet sexy menace of the bad boy, captured perfectly in a long shot of his brooding face as he stares down someone who threatens Mina in an absinthe bar. Coming across the two of them later conversing on the terrace, Lucy aptly sums up their sexual chemistry in her snide quip, “Heathcliff and Cathy on the moors.” The show even has a feminist edge, with Mina reinvented as a med school student whose engagement to Jonathan is derailed when he expresses the view that she should give up career for “more natural pursuits” as his wife. Dracula, who has supported Mina’s ambitions from afar, confronts Jonathan about his hypocrisy in wanting to rise above his given social status himself while denying Mina the same opportunities to defy gender roles, and the two are reconciled, although the bad-boy Dracula remains better equipped to deal with a strong female partner than the good-boy Jonathan – a pattern repeated in a number of supernatural romances from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to The Vampire Diaries.

The series is beautifully Gothic in atmospheric scenes of fog-obscured London streets and mysterious caped figures, and features enough balls and other upper-crust events to satisfy all the costume fetishes expressed in steampunk culture. Between its politics and its polish, Dracula is the most intriguing new series thus far this year.

¤