THE LAST OF THIS YEAR’S new science fiction programs, Fox’s Almost Human, debuted this week, a co-creation of J.H. Wyman and J.J. Abrams, who seems to have his hand in most things science fictional these days. Wyman and Abrams first teamed up for Fringe, a reinvention of The X-Files with less government conspiracy theory and more of Abrams’s distinctive Lost sensibility. Billed as the next stage of police television, Almost Human is much less innovative than it claims, reworking the well-known terrain of the cross-ethnic cop-buddy formula common in the 1980s. Graham Baker’s film Alien Nation (1988), written by Rockne S. O’Bannon and adapted to a short-lived television drama, extended this formula into science fiction by pairing its human detective Sykes with an alien “newcomer” partner in stories that directly confronted issues of racial prejudice long before Neill Blomkamp used the same conflation of aliens and racial “other” in his District 9 to similar ends. In the cross-cultural, cop-buddy drama, the “neutral” white partner’s stereotypical attitudes toward the racial other are gradually eroding so that friendship and new understanding can emerge. The police drama In the Heat of the Night, adapted to television in the 1980s along with the television Alien Nation, paired white and African American cops policing rural and overtly racist Sparta, Mississippi, and gives a sense of what is at stake in such dramas. And long before Alien Nation used the cop-buddy formula to explore issues of racial difference, ABC’s Future Cop (1976-78) explored the idea of contrast between theory and practice in its fraught relationship between veteran cop Joe Cleaver, played by Ernest Borgnine, and his letter of the law robot partner Haven, played by Michael Shannon, now well-known for his work on Boardwalk Empire, whose most recent SF appearance was a General Zod in Man of Steel.

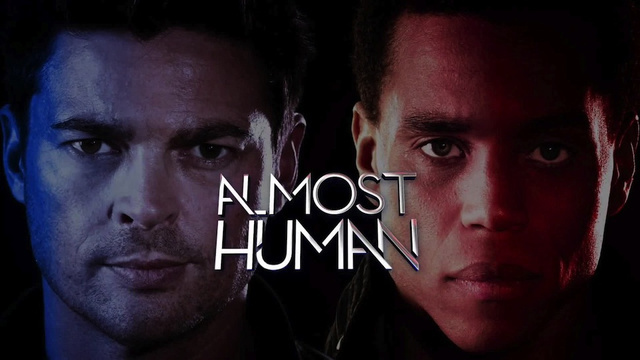

While Alien Nation paired its crusty human cop with an alien, Almost Human pairs hard-boiled John Kennex, played by Karl Urban who plays McCoy in Abrams’s new Star Trek, with an android partner played by Michael Ealy. This, too, is hardly uncharted territory. In the 1950s Isaac Asimov’s detective Elijah Baley worked with robot partner R. Daneel Olivaw in Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun, works that have been adapted to screen a number of times. The Asimov film adaptation I, Robot, (2004), directed by Alex Proyas, draws on this formula in its pairing of Will Smith’s detective Del Spooner with the robot Sonny, including the ubiquitous need for Spooner to overcome his irrational suspicious of all robot others. Mann & Machine (1992) tested the limits of this formula to interrogate gender difference when it paired its Detective Mann with a sexy robot partner Eve Edison, played by Yancy Butler, who went on to star as another sexy, supernatural detective in the live-action, comic book adaptation Witchblade (2001-2002). But it is the Canadian television series Total Recall 2070 (1999), taking its atmosphere from Blade Runner although its title from another Philip K. Dick work adapted to screen, that comes closet to the look and feel of Almost Human. Its detective David Hume (Michael Easton) is paired with android partner Ian Farve (Karl Pruner), in a cyberpunk-style future in which the corporate Consortium dominates. Like Almost Human, Total Recall 2070 investigates crimes linked to illegal research and abuses of technologies related to genomics and memory. RocoCop, returning to big screens in 2014, is another antecedent here, which its vision of the formally human Alex Murphy and its plot about a dystopian Detroit destroyed not by rising crime but by the privatization of the police service in the interests of the evil OCP, Omni Consumer Products. Once a character in a satirical film about an exaggerated dystopian future, RoboCop has now become a mascot of sorts for a contemporary Detroit economically abandoned by the rest of the country, a dark city of the science fictionalization of everyday life captured in the documentary Detropia (Ewing and Grady 2012).

Yet just because Almost Human is not original does not mean that it cannot do interesting things with its established formula. Unlike Future Cop, for example, which continually emphasized the necessity of Cleaver’s ability to respond to situations contextually and intuitively over Haven’s overly rigid use of abstract laws, Almost Human in many ways presents Dorian as more human than Kennex. Kennex is the quintessential isolated and cynical outsider cop, well known from police procedurals such as Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch series, and as such doesn’t know how to play well with others. Kennex is also haunted, as such characters always are, by a past in which his human partner was killed, an incident in which he lost a leg and then spent two years in a coma, further emphasizing his isolation from the rest of the world which went on without him. As the series begins, Kennex blames androids for his partner’s death in the familiar formula of rule-based values vs. human values: the android refused to help evacuate the mortally wounded man, explaining that he needed to focus on aiding those “with a better statistical chance of surviving.” Yet as the rather clichéd melodrama over the first two episodes reveals, Kennex is projecting into blame his own guilt for leading the men into what proved to be an ambush; worse, as he discovers using an illegal technology to accessed his memories of that day, they were betrayed by his girlfriend who disappeared after the event.

Almost Human might be a really good series. Our comfort with robots interacting with us as ubiquitous parts of our daily life has increased since the 1970s Future Cop, which articulate then-contemporary fears about humans being replaced with automation. In the neoliberal era of precarious labor we have perhaps become all-too-comfortable with the idea of humans being replaced by machines, evident in our interactions in automated call-center help-lines, our companionship with Siri, and all the other ways in which we perform for ourselves, with machines, tasked once performed by humans, from bagging our own groceries to refilling our prescriptions online. Wyman has said that Ray Kurzweil’s rapture of the nerds articulated in The Singularity is Near is an influence on the show, and so if nothing else Almost Human marks a significant shift from its predecessors in the greater sympathy we have for Dorian: unlike other cross-cultural buddy shows, our identification is immediately with Dorian rather than gradually won alongside the winning over the human partner. Kennex, too, is won over pretty easily and, contra theories of the uncanny which suggest that we find most disturbing artificial beings that are almost but not quite human, preferring a clear distinction of the evidently artificial and evidently human, Dorian is all the more sympathetic when contrasted with the inhuman coldness of the more recent android models who do not have this “flaw” of programmed emotion and empathy.

The most promising innovation of this series is that it is really Kennex rather than Dorian who is almost human: he has a synthetic leg to replace one lost in the explosion that killed his human partner, and he struggles, as his fitness-for-duty evaluation states, with “psychological rejection” of this synthetic body part. He is also fusing with machines in his memory-recall experiments, and his obsession with vengeance for the attack that killed his partner makes him considerably more rule-bound and rigid than Dorian. Yet Almost Human fails to explore the metaphor of ethnic and other prejudice rooted in this formula, as did the earlier Alien Nation and even Mann & Machine. Dorian objects several times to the term ‘synthetic,’ which Kennex clearly uses as a slur, but thus far the plots of the episodes, particularly the second one about slaughter woman women to create better quality skin for synthetic sexbots, emphasize and reinforce the difference between humans (who count) and androids (who don’t). The episode narratives are thus in tension with the thrust of the series premise, positioning Dorian as the “exceptional minority” except from a prejudice that is otherwise warranted against others of his kind, making the politics of Almost Human potentially more regressive than those of the 1970s Future Cop.

¤