By Zoë Hu

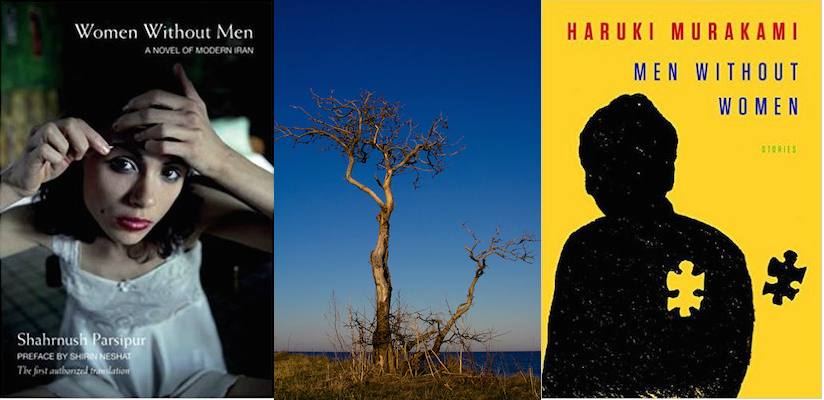

Seeing no alternative, a woman plants herself in her family’s courtyard and sprouts into a tree, begging aghast visitors, “Don’t cut me down. Let me grow.” Her name is Mahdokht, and her germination as human-cum-sapling has a loyal chronicle in the Iranian modernist novel Women Without Men, written by Shahrnush Parsipur in 1989 and first translated into English 10 years later. The text follows five women as they escape Tehran, shrug off dreary brothers and husbands, and — aided by the occasional, benevolent dollop of magical realism — find their way to a garden refuge. Rooted at the center of this botanical sorority, Mahdokht the tree-human is cared for and cultivated by the other women. She is also their witness, keeping time with her gradual growth to the loneliness and struggle that mark their isolated existences. Women Without Men asks its characters to begin new lives, free from the social mandate of a male partner, but once in the garden this possibility opens onto foreign, craggy territory. Unable to transform into a tree herself, one woman feels that nevertheless she is “rotting from within.”

Trees also abound in Haruki Murakami’s new short story collection Men Without Women. So, of course, does loneliness. Cheated on, divorced and betrayed, the men in Murakami’s work are more often than not the ones left behind. Each story describes the slow spread of their solitude, which “seeps down inside” their bodies, “like a red-wine stain on a pastel carpet.” For these characters, the outside world is held at a distance, as muffled and faraway as a knock on the door barely heard in one’s sleep. Trees function as the ambivalent testimonies of this condition. In one story, an old willow stands watch over the lonely existence of a young bartender, who in the midst of a nervous breakdown clings to the memory of this tree, which “had protected him and his little house.” In another story, a man imagines solitude as a hard winter that makes trees grow stronger and carves “growth rings” into their trunks. But after remembering his own acute loneliness, a time in his life when he would “go a week without talking to anybody,” he is left unsure what any of it means. “Whether this period…left valuable growth rings inside me, I can’t really say.”

Though the titles of both texts take absence as a central premise, the lives of their characters describe a loneliness that goes beyond the physical or social. Zarrinkolah, a prostitute in Parsipur’s universe, is surrounded daily by men, yet finds their presence terrifying because they appear to her as headless. She guards her fright as a shameful secret, enduring her mutilated clients and the fellow women of her brothel, who she fears may accuse of her insanity, in silence. Deprived of any fellow understanding, she remains cloistered into a worldview that is both dreadfully senseless and reserved exclusively for her.

Similarly, the men in Men Without Women are never truly without women, often soothed and visited by a faithful cast of nurses, female locksmiths, and even lovers. Yet these interactions are bloodless and unsatisfying, and the men remain sunken into themselves and a discontent they fail to articulate. As Murakami writes, “For Men Without Women, the world is a vast, poignant mix, very much the far side of the moon.” To be a character in this collection is to occupy a different world, where daily happenings seem to always pitch differently and off-tune. Names, feelings of thirst, and even “the way baristas at Starbucks treat you” change. Loneliness is not the consequence of being without men or without women, but rather its precondition.

To read Parsipur and Murakami’s works side by side is to identify more clearly the dark current roiling under the basic premises of these texts, which go far beyond examining the absence of a gendered counterpart, or the banalities of a break-up or divorce. Rather, both works are concerned with a specific condition of loneliness, one in which afflicted characters don’t know exactly what they want, but know they want more. Munis, a young Iranian woman in Parsipur’s garden, is driven mad with desire for a change she can’t fully envision. “How can I turn into light?” she moans. Meanwhile, Murakami’s Habara expresses a similar urge to “inhabit another time or space,” to become a nameless “lamprey eel” thinking “very cloudy but pure” eel thoughts. Removed from the webbed connections of human intimacy, these solitary characters seek a transcendence that will boost them one step higher above their already effected disconnect from the real world.

The loneliness of being without men or women also brings with it an unerring claustrophobia. Parsipur’s novel is replete with references to walls, dusty window panes, and air so laden with smoke and dust that it becomes almost material. Meanwhile, three of the stories in Men Without Women unfold without characters ever leaving the confines of their homes. In both works, men and women maintain thinning connections to the world through radio shows or half-hearted postcards. Any desire to travel is inevitably thwarted by catastrophic detours, by pit-stops that become destinations.

¤

Literature has never shied from stories of loneliness, but often the most popular loners of Western canon capitalize on their isolation as a refined vantage point from which to observe the surrounding world. Outcast poster-child Holden Caulfield, who professed to feeling so lonesome “I almost wished I was dead,” refracted his existential gloom onto those around him, using the privilege of distance to critique a hypocritical and image-obsessed America. Whether in Camus or Morrison, the isolation of an individual has often served as the indictment of a whole. In Men Without Women and Women Without Men, however, characters remain stubbornly self-centered and unable to relate to the people in their lives — much less observe them. Murakami’s collection opens with a story in which one character tells another that “the proposition that we can look into another person’s heart with perfect clarity strikes me as a fool’s game.” Examining ones own heart, however, “is another matter” — and the importance of self-understanding repeats like a refrain throughout the six other stories. Kino the young bartender, whose sparse existence is limited to his bar and his collection of jazz records, spends a night tormented by the beating sound of his own heart. The end of his story arrives in a moment of epiphany — and perhaps salvation — when he says aloud to himself, “Yes, I am hurt. Very, very deeply.”

For Kino, as with many other characters in both texts, verbalizations of despair remain directionless, hurled into empty rooms or courtyards; with the exception of the last story in Murakami’s collection, character portraits never bear the confessional tone of an address to the reader. These men and women do not seek the comfort or response of an outside listener, but rather a more permanent imprint, the projection outwards of an internal turmoil or thwarted desire. One solitary Murakami character, newly obsessed with calligraphy, believes that “the black symbols flowing from his brush onto the pure white paper could somehow lay bare the workings of his heart.” As outsiders peering into these characters’ lurching gestures towards self-expression and self-documentation, readers are rendered voyeurs, not confidantes. This sensation calls to mind Wong Kar-Wai’s 2000 film In the Mood for Love, an aching meditation on the loneliness shared by two tenants living in the same apartment building in 1960s Hong Kong. In one scene of the film, the protagonist (played by Tony Leung) relates to a friend how wanderers in a past era would climb mountains and whisper confessions into the holes of trees; at the end of the movie he embarks on this same quasi-pilgrimage, choosing a worn temple door as the receptacle of a secret that, ultimately, remains inaudible to the viewer. Similarly, in Parsipur’s novel, Zarrinkolah runs to the local bathhouse to weep over her visions of headless men, inspired by the knowledge that “when His Holiness Ali couldn’t find anyone to trust with his thoughts, he would go into the desert, lean into an abandoned well, and tell his secrets.” The desire to speak, coupled with the ambivalence towards finding an interlocutor, marks and amplifies the particular strain of loneliness found in Parsipur and Murakami’s stories.

Knowing oneself enough to articulate one’s personal reservoir of secret hurt is perhaps the only defense available to characters without men and without women — who are so desolate they are often in danger of starving, rotting away or turning transparent “like a freshly caught squid.” Untethered from the same emotional reality that girds everyone around them, characters must figure out how to keep their hearts, now “devoid now of any depth or weight,” from “wandering aimlessly.” Knowledge of the self can be a strategy for shoring up an identity in slippage. Munis, one of the female gardeners in Women Without Men, realizes that she has an “unbounded awareness of things,” but a limited understanding of herself and her own body. She decides to embark on a transcendental journey and “descend to the depths, to the depths of depths,” where, she is told, “you will see the light aglow in your hands.” Meanwhile Mahdokht’s transformation into a tree grants her a self-awareness that is almost painfully rich in detail, as she embarks on a contemplation of growth that takes the measure of every new leaf or creeping root. Her heightened sensitivity reaches an apex when, through spasms as unbearable as “birth contractions” she bursts into a mountain of seeds that are swept by the wind to “all corners of the world.” Among a troupe of reclusive and childless characters, Mahdokht’s taut self-awareness snaps into one final, expansive act of creation — a multiplication of the self, instead of its erasure.

¤

Many differences exist between Men Without Women and Women Without Men and the cultural contexts illustrated in the two works. Women Without Men focuses particularly on the stifling social restrictions that box in female characters, who grapple with gendered norms alongside a more personal ennui. Parsipur was jailed after her novel’s publication, and both her autobiography and her storytelling demand readers to pay special attention to the historical specifies of being a woman in Iran in 1953, the year the novel is set and the year Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup. However, both Murakami and Parsipur share the same vital concern for the core sensations of human loneliness, and privilege the interiority of their characters above the social implications of their solitude. Most notably, loneliness according to Parsipur and Murakami is often edged with an unlikely, magical quality. Women grow into trees, insects turn into men, and as is typical of Murakami, cats herald mysterious happenings. In comparing the two works, a reader gains the sense that so much of loneliness is fantastical, its grip noncommittally dangling victims somewhere above the border between the mundane and the unbelievable. Detached from their surroundings, characters become submerged into personalized universes where strange occurrences are never out of the norm. These occurrences are not meant to be deciphered as allegories, but waver in and out of characters’ lives like half-formed dreams. When she arrives to Parsipur’s garden, Munis declares, “I have taken the first step to discover a new jurisdiction, a new set of laws.” Loneliness, after all, is its own unreal condition.