On a sunny Southern California day in 1946, Howard Hughes crashed an XF-11 prototype into an unsuspecting Beverly Hills neighborhood. Narrowly escaping with his life, the accident was the aviator’s highest profile crash but certainly not the only one in Hughes’s life. Some have wondered if the regular battering of Hughes’s body led to his increased eccentricities over the years — something that can be seen in his treatment of women during Hollywood’s Golden Age.

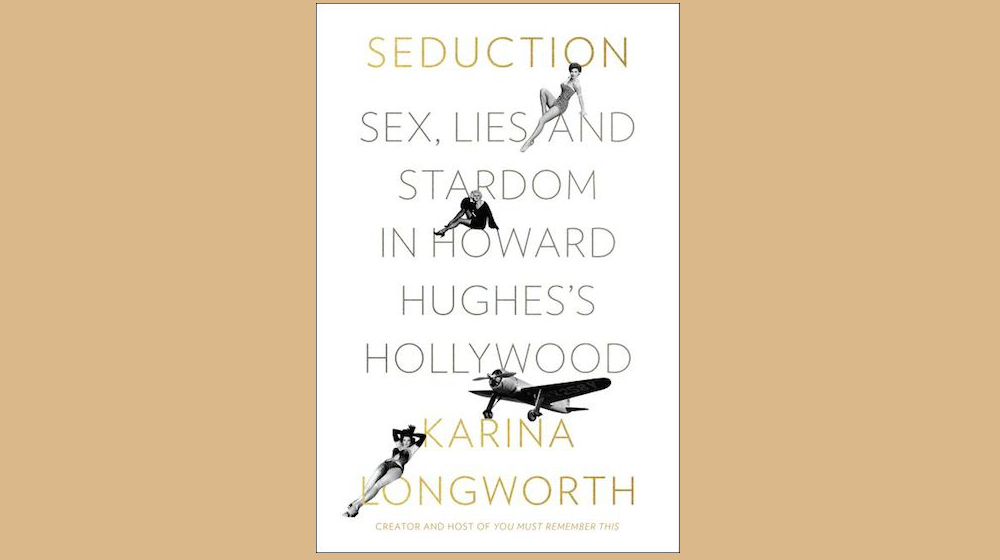

The latest foray into Hughes’s life is Karina Longworth’s Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood. Longworth is the creator and host of You Must Remember This, a popular podcast that focuses on Hollywood’s Golden Age.

As Longworth told The Hollywood Reporter, “Whenever I hear that so-and-so was famous for having slept with a lot of women, I wonder what the women felt about that. And so I just thought it would be more interesting talk about the experiences of the women and how they perceived Hughes, and what their experiences were like being involved with him professionally or personally.”

Seduction is not a biography, but a meandering journey through Hollywood’s Golden Age as seen through the lens of women who met, and often slept with, Howard Hughes. The book begins with a story about Hughes’s family — his father, a businessman in Houston who made the family fortune by patenting drill bits, and his uncle Rupert, a writer in Los Angeles known for the book and adaptation of Souls for Sale (1923). When Howard Sr. died, family tried to take the fortune from Howard Jr. (who was then a minor), an experience that would lead Hughes to remain childless — no one to steal his fortune when he grows old. Once his father passed, Howard moved from Houston to Hollywood.

One of many film companies Hughes would found or take controlling stock in was the Caddo Company. Caddo’s first production was Lewis Milestone’s The Racket (1928), a bootlegging tale that was highly censored around the country. When pushed by censors about the film’s depiction of brutality, Hughes responded, “I won’t tone anything down. I believe the screen is a powerful instrument. It bores through opinions like my father’s bits bore through rock.” Battles with local and national censors would be a defining element of Hughes’s time in Hollywood.

By 1927, Hughes had his focus on the aviation epic Hells Angels (1930), which began as a silent film and was reshot as a talkie. Overconfident, Hughes was willing to spend half a million dollars on the project. Once the film got off the ground, that half a million was spent on antique World War I airplanes, pilots, and mechanics alone. Those who have seen Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator can get a sense of the careless spending that was going on during the production of this film, including the abrupt move from Los Angeles to Oakland to reshoot dogfight scenes with clouds in the background.

In addition, four people died during the filming, three of the deaths were connected to the film. Two airplane crashes killed pilots while another crew member died moving a plane. During one shoot, Hughes pushed his pilots to enact a low-altitude maneuver. The pilots said it could not be done. Never responding well to pushback, Hughes attempted the stunt himself. Having only earned his aviation license in 1928, the newly minted pilot failed and crashed horribly resulting in reconstructive surgery that marred his appearance.

During this time, Hughes would do two things that helped solidify his place in Hollywoodland. First, he hired Lincoln Quarberg to help with publicity. Hughes was obsessive about many things, so it should surprise no one that he not only monitored how the press covered him but he also fed the media information as a way of controlling what they covered. Second, Hughes began a relationship with the sexy Hollywood starlet Billie Dove — creating a true representation of the “beautiful girl” and “rich man” stereotype.

After purchasing a production company that would release The Front Page (1931), Hughes continued to cast Dove in his productions in hopes of keeping her career alive. Like many stars of Silent Hollywood, Dove’s career was waning after she starred in The Age of Love (1931) and Cock of the Air (1932) — a film for which Hughes would get serious censorship pushback. The censorship squabble over Cock of the Air did not do Hughes any favors when Scarface (1932) went into production.

Hughes’s relationship with Dove wouldn’t last as her career was waning just as Hughes’s was lifting — perhaps a real life version of A Star is Born.

While Hughes’s next girl was Ginger Rogers, the dancing beauty who was on the rise in a series of musicals for Warner Bros, Longworth shifts focus to Jean Harlow. Hells Angels instigated Harlow’s “blonde bombshell” status, and how Hughes needed to find her work. Loaning her out to other studios, Harlow appeared in such films as The Public Enemy (1931), Platinum Blonde (1931), and Red-Headed Woman (1932). While many insinuated a sexual relationship between Hughes and Harlow, the formal communication between shows the more likely story of a contentious business relationship. Harlow made good money for her films, but Hughes raked in major cash because he owned her contract — one of the benefits of making and maintaining a star. Hughes would sell her contract to MGM in 1932.

The next woman associated with Hughes was the indispensable Katherine Hepburn. Although Hepburn would largely consider her life’s great love to be Spencer Tracy, the affair between Hughes and Hepburn was also cemented into Hollywood lore. Seduction traces the relationships and conspiracies over the years, including the notion that perhaps both Hepburn and Tracy were gay and served as beards for one another. Hughes would ultimately meet Hepburn by forcing himself into her golf lesson. In true Hughes fashion, the aviator landed a plane on the Bel-Air Country Club fairway. This undoubtedly got Hepburn’s attention, but she would instead run off with director John Ford after filming Mary of Scotland (1936). Eventually Hughes and Hepburn would connect. The two would their mutual interest in dodging crowds and still managing to get attention.

It wouldn’t be long before Walter Winchell’s gossip column featured a headline about Hughes’s next, though brief, affair with Bette Davis. Moving on to another Warner Bros. actress, Hughes took Olivia de Havilland to a party at Jack Warner’s house and continued to court her. Interested in career over love, de Havilland would also brush Hughes away.

Circling back to Ginger Rogers, Hughes professed his love, proposed marriage, and promised to build a house for her with a view of Lake Hollywood and the Hollywood Sign itself. Rogers was smart enough to wonder if Hughes just wanted to build a house for a beautiful woman so she could be his co-recluse. The relationship would dry up when Ginger confronted Hughes about his infidelities.

Many of the stories throughout Seduction move beyond Hughes, but always come back around to connect with Hughes’s obsessive personality. Hughes regularly purchased contracts of rising stars so he did not have to negotiate with a studio — and so he could control their life. Control was paramount for Hughes. Between airplanes, movies, and women, Hughes sought to maneuver everything in his life like puppets on a string. Many women featured in Seduction grew wise to Hughes and went on to have strong careers. Others were not as lucky, as Hughes became increasingly restrictive with his significant others.

In addition to actresses like Hepburn and Davis, Jane Russell would find herself as resident sexpot in The Outlaw (1943) a Western directed by Howard Hawks before being ousted by Hughes for not following orders. Another brunette temptress, Ava Gardner, fell into a lengthy relationship with Hughes in the 1940s. When Gardner starred in The Barefoot Contessa (1954), she believed her character was modeled after her own time with Hughes.

As Hughes aged, his relationships became increasingly questionable. For example, Hughes purchased the 1941 studio contract for Faith Domergue and proposing marriage to the 17-year-old (when Hughes was in his late 30s). Instead of helping her career, Hughes became more interested in war contracts after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The result was Domergue finding herself less and less connected to the outside world, increasingly gaslighted by Hughes about gallivanting with the likes of Lana Turner, Rita Hayworth, and others.

Like the many illuminating episodes of the You Must Remember This podcast, Seduction reads like a scandal sheet tempered with primary and secondary research. Listeners familiar with Longworth’s recent series investigating Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon will find a similar set of gossipy tales sorted through a historiographical lens. Seduction is a fun read, providing a sense of what it could have been like sitting at a table at Ciro’s in Hollywood, listening to the stars gab.