All women think they are different, Simone de Beauvoir writes. They all think there are some things that will never happen to them. And they are all wrong. There are many women, no longer in the flush of youth, who find themselves horrified to discover themselves in black tangles of circumstances they never would have imagined.

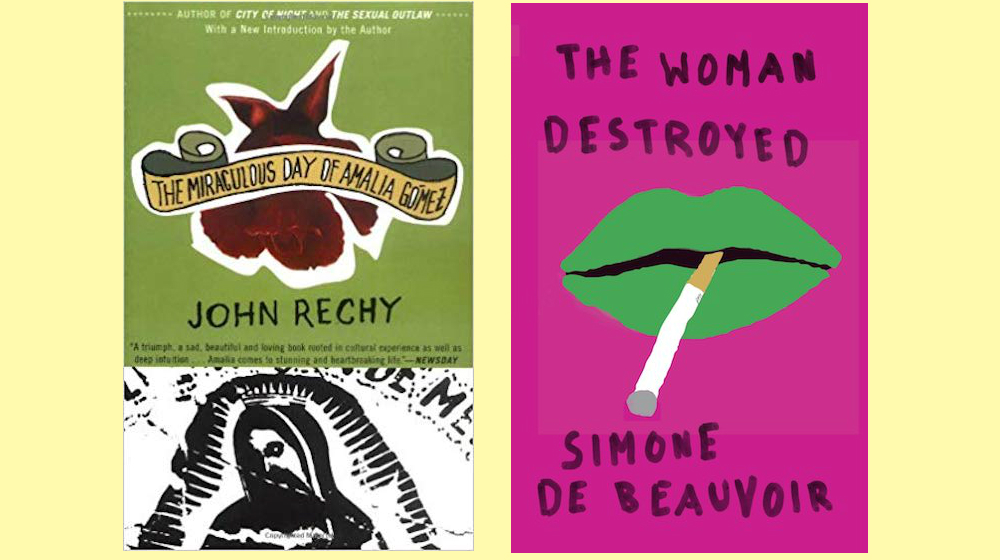

There are two ways to go with this. The first is complete ruin, exemplified by Simone du Beauvoir’s Monique in The Woman Destroyed. At 44 she finds her seemingly safe and insulated world shattered by the discovery of her husband’s affair. That and the simultaneous emptying of her nest by both her daughters and her husband. The second is resurrection, like Amalia Gómez in John Rechy’s The Miraculous Day of Amalia Gómez.

Rechy’s work, told in the course of one day, slashed with knife-like flashbacks, has protagonist Amalia, a Mexican woman, living in one of the decaying neighborhoods off Hollywood Boulevard. She awakens one morning to the sight of a large silver cross in an otherwise clear sky. Was this a miraculous sign that things would get better or simply streaks of smoke? Miracles do not come to a twice-divorced Mexican woman, with rebellious adult children, who is living with a man not her husband…do they?

Amalia follows the trajectory of many women who find themselves wondering what the hell happened. A beautiful flower of a girl, she is brutally raped by a boy she thought liked her. Then she is forced by her parents to marry that boy. You know where this is going with the boy. Salvador — his name means “savior,” and names carry a great deal of significance for Amalia — beats her, joins a gang, shoots up, and abandons her and their child.

Burdened by this traumatic experience and the responsibility of caring for a young one, Amalia bounces from man to man, seeking safety, only to find herself with less safety and more children. Amalia goes from being a maid for affluent whites to working in a sweatshop to trying other ways of scratching out a means of survival for herself and her three young children.

How did Amalia, who sought only to please and basked in delight when called “m’ija” — my daughter — end up like this? The story has her tied to her mother, an emotional bully, who constantly taunts and blames Amalia for her misfortunes. Unsurprisingly, her mother’s problems stem from her own jealousy and unhappiness, not Amalia’s actions.

While Amalia prays to a prized image of the Blessed Virgin, an immaculate deity surrounded by light in glorious robes, Teresa, her mother, lugs around her own Blessed Virgin, “La Dolorosa,” a black velvet robed statue with a face of constantly endured pain.

Amalia’s naïveté can become annoying, with her constantly pleading to a seemingly deaf Blessed Virgin, but we all have our means of self-protection. Sometimes this makes her narrative a warped reality, as it is distorted through a protective veil of self-justification and a subconscious refusal to see the truth.

“When did they change toward me? Why? What do they have against me?” Amalia agonizingly wonders about her formerly loving children. She did everything she ever did for their benefit, didn’t she?

Was it because of her forbidding them to call her by “Amita” when their older brother Manny was killed in jail, seemingly at the hands of the guards, and the wound of his death was too fresh? Hadn’t she hugged them right away and told them she didn’t mean it? Didn’t they appreciate the long hours she worked or the “father” and bill payer Reynaldo she had living with them, who loved them and put food on the table?

Reynaldo loved Amalia purely. He loved her children as if he were actually their father. Didn’t they see that? How did her tiny, sweet Gloria turn into a hard-eyed young woman with teased hair, who carried a knife in her shiny black boot? And where was her sensitive, handsome son Juan, who distained menial jobs, suddenly getting his money from?

Amalia’s pained and confused personal life takes place alongside the constant pressure and stigma of poverty and discrimination that the Chicano population faces. She passes an old man relaying the story of his younger days, when tired of being treated without dignity, even while Chicano sons were dying for their adopted country in Viet Nam, he and others staged a protest, shouting No mas! No more abuse! No more!

While Amalia is “legal,” many of her compatriots are not. They are often exploited by coyotes, men of their own race who smuggle them across the border only to abandon them in desolate areas, kill them, or sell them to “la migra” — border patrol guards — so they can win accolades for turning them in.

Amalia’s friend Rosario, a strong and clear eyed character, passionately says to Amalia in the sweatshop where they work, “Every day hundreds — a thousand now — are arrested for crossing the border — every day — risking danger because they’re hungry, fleeing poverty, risking la migra hunting them down like animals, with horses, helicopters, brutal ambushes to keep the desperate people away — and from what? From jobs no one else would take? … And those who reach the cities? Slums! The Streets? Terrorized by gangs and violence and the migra always tracking them down. Illegals? Huh! How can a human being not be legal?”

Amalia, John Rechy has said, was an extremely real character to him. In an interview with UCLA professor Hector Calderon, he speaks of the perfection of coincidence when after he himself sees, while sunbathing in Griffith Park, a perfect cross in the sky and wonders what a Chicano woman living in the projects would make of it? A miracle?

As Rechy walks into a drugstore to buy a sunbathing chair, he sees the living Amalia, a woman with thick, wavy black hair, impressive breasts, slit skirt, and pumps, in a style entirely her own, strolling the aisles. After the sudden questioning appearance of her aggressively mustached man, the author left the drugstore and walked the very streets where his Amalia would live and looked at the various things his Amalia would see. And Amalia Gómez was born, the written offspring of a writer and the personification of his ideal.

“You’re a very smart woman, Amalia, perhaps smarter than you know — but what good does it do you, corazón,” her friend Rosario continues. Puzzled, Amalia asks what she means. “Think. Just think” is the answer. This is in her subconscious as she walks though her streets in Hollywood, like Joseph Heller forced Yossarian to do in Italy, as if through the streets of Hades.

Nightmarish sights assault her, shootings, two Mexican men harassed by the police for seemingly no reason, a ragged woman crawling on bloodied knees up the stairs of a church offering her pain and sorrow to God’s glory, gang members, a boy in the bloom of youth getting shot by members of a gang while leaping to slam dunk a basketball.

She seeks succor in a church to find the peace of confession only to realize her confessor is masturbating to her confession. Getting further and further beat down, like de Beauvoir’s Monique who finds herself seeking hope from magazine astrology columns and handwriting analysts, Amalia seeks salvation in faith healers, and then again back to the church where she begs, pleads, and reasons with the cold statute of the Blessed Mother before finally demanding a miracle from the immobile statue.

Rechy states that this was an extremely painful book for him to write, as Amalia goes from horror to horror to horror. He shares that it was necessary for her to face total disaster, in order for her to finally face the truths her self-defense mechanisms had hidden from her, and thereby achieve salvation. Her thoughts slash her like harpies, until a confrontation with her children causes her veil of self-protection to be ripped away, revealing the ugly, sordid truths of her life. Only in that moment is she granted a chance at salvation.

Seeking her friend Rosario for guidance, who is on the lam for helping a friend hide from the police, because he killed a crooked migra agent for his part in his son and daughter-in-law’s disappearance, Rosario exhorts her: “you’re left to find your own strength, corazón, you don’t accept that you must be a victim.”

Leaving her streets of poverty, Amalia walks, sweaty and disheveled, into an expensive mall in a more affluent area, not realizing at first that the stares of the people are not due to her beauty and lushness, but due to her outsider status as an obviously poor Mexican woman who has no place in their mall.

Before she can fully comprehend the indignity of this, she is grabbed by a crazed eyed gunman who, pressing his gun against her temple, threatens to kill her if the police do not drop their weapons. Feeling the cold iron pressed against her head and hearing the tiny click at her ear signaling the bullet sliding in place to kill her, Amalia finally breaks out of her paralysis and victimization, screaming “No more!” and thrusting the man away from her.

Shots are fired and through the iridescent rainbows of shattering glass that blazed, shimmered and sparked as they fell on the red of spilled blood and the glaring light — Amalia finally sees the Blessed Mother with her arms outstretched to her.

John Rechy has said that those who wish to believe that Amalia did receive her miracle in the form of her heavenly vision could be right and those who wish to believe that her vision was the result of an overwrought mind in the glare of lights could be right. Her real miracle, Rechy says, was her finally screaming the battle cry of the Chicano movement, “No more!” and shedding her status as victimized woman once and for all.

And unlike Simone de Beauvoir’s frightened, broken Monique, isn’t this what women should do?