Back in the analog ages of 1955, Frank Sinatra produced his first 12-inch LP album, In the Wee Small Hours. It included a popular song, “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” which is the song Garry Wills is singing in his latest book Why Priests? A Failed Tradition. Wills claims that some of his best friends and teachers have been priests, and he does not feel any animosity, but “the fact that I can get along without them very well does not mean that I expect them to disappear, or even that I advocate that.” Wills aims only to assure his fellow worshipers that “as priests shrink in numbers […] congregations do not have to feel they have lost all connection to the sacred just because the role of priests in their lives is contracting. If Peter and Paul had no need of priests to love and serve God, neither do we.”

And there is the nub of Wills’s argument — for too long in the life of the Roman Catholic Church the laity have only known Jesus or God as through a glass, darkly, via an indirect, mediated relationship to the Divine, where the prime mediator has been the priest. Catholics can do better, and deserve better, and (in the spirit of St. Francis of Assisi) need to bypass these go-betweens to achieve a more personal, direct, unmediated connection with the foundation of their beliefs. The major theme of the book is that the priesthood has no origins in early Christianity, while claims that it represents an unbroken line of “apostolic succession” are based on a “chain of historical fabrications.” It is an accretion of a monarchical, hierarchical Church, out of touch with its origins. Why Priests? is not so much about a failed tradition as it is about a bastard tradition, without heritage or pedigree.

Priests become obstructive to authentic belief; they keep their congregations in childish awe as they perform their magic. They are inventions of managers and corporate types. In a multinational corporation like the Roman Catholic Church, they help maintain the brand image and control of a monopoly product — they fortify “the monopoly on sacred things.” Through the centuries the priesthood has fostered much of the condemnation and persecution the Church is famous for, doing so because of the “jealousy of prerogative, the pride of exclusivity, the desire to define one’s own Jesus as the only Jesus…”

PBS viewers (and people of all faiths) will enjoy Wills as a Catholic Doc Martin, someone who does not suffer fools gladly, who cuts right to the heart of the matter, gets down to brass tacks. In true Doc Martin style, Wills does not mess around, and eliminates the suspense by answering his own question, “Why Priests?,” on just the second page. We all have our favorite solution for a shortage of priests — ordaining female priests; bringing married men into an all-celibate male priesthood; following the revised policies of the military, and allowing gay priests to serve. No, says Wills, “the real solution is: no priests.” And yes, we can imagine a Christianity without priests.

From that idiosyncratic start, Wills is off and running, devoting the remaining pages to a profound, scholarly, scriptural exegesis of the sources, the evidence for his claim, “dispassionately, thoroughly, historically.” For example, in the whole of the New Testament, you will not find a single priest, or church, mentioned in the first generation of the Jesus movement within the Jewish community. But why no priests? Because, in the long life of Catholicism, the concept and practice of the priesthood has had two main negative effects: it has kept Catholics apart, separate from other Christians, and more important, “at a remove from the Jesus of the Gospels, who was a bitter critic of the priests of his day.” This is a populist book in the sense that Wills wants the people of God to reclaim their religion from the Pied Piper priests who have led them astray.

This is an iconoclastic work that demolishes cherished shibboleths. It is clearly meant to disturb the status quo, to arouse, to goad to action, to create enough shock and awe to arouse Catholics from the unthinking, unreflective stupor (often characterized as a “pray-pay-obey” learned helplessness) that their ministers have lulled them in to. Chapters have take-no-prisoners titles like “Killer Priests” and “Priestly Imperialism.”

“Killer Priests” reminded me of another author at the other end of the religiosity spectrum who, like Wills, is also very critical of the Catholic Church. Atheist Phillip Pullman, in his fantasy tale His Dark Materials, has a priest character, Father Gomez, who roams the world assassinating the Church’s enemies. Killer Priests, however, despite its Spielberg title, is actually an examination of the role and fate of prophets in the Judaic tradition, centuries before Christianity. Prophets, like Jesus, were anti-establishment boat-rockers, while “priests,” both by tradition and heritage, were elite members of the establishment courts and temples. Prophets are bothersome to the established order — they exhort, they chastise, worst of all, they remind: empty formal gestures are no substitute for moral reform. Prophets, like Jesus, even condemned the Jewish priesthood. As a result, Jewish authorities killed a Jewish prophet: “The priests killed Jesus. That is what they do. They kill the prophets.”

As for priestly imperialism, that’s the result of the claim of St. Anselm (Archbishop of Canterbury 1093-1109), that Jesus died for our sins by becoming the sacrificial victim required by a strange, punitive, vengeful God to “atone” for the sins of mankind. If you further claim that Jesus was a priest, then the victim/priest combo, coupled with a theory of apostolic succession, gives you an exclusive priesthood: only a priest can replicate Jesus’s victimhood when he offers the “Holy Sacrfice of the Mass,” as it is commonly referred to in Catholicism. Wills says it takes a lot of theological imagination to make claims like this, but once the priest got the exclusive right to perform the sacrament of the Eucharist at the altar, “…he pushed out imperially to conduct all the other sacramental transactions of the church.” The priest became the sole go-to guy for everything from baptism to matrimony, and the power and control of the hierarchy over the laity was thereby consolidated. For Wills this was a usurpation of lay power, since laypeople were the first baptizers, due to the absence of priests in the New Testament. He further provides very personal details of his own life story to bemoan “the way priestly control can spread to all facets of Christian living.” (He would find a sympathetic ear in Thomas Jefferson, who wrote in 1813: “History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government.”)

When the priest says Mass, he recreates and commemorates the Last Supper of Christ (a Jewish seder) by performing the miracle of transubstantiation, or the magical metamorphosis of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. At least that is the official explanation given in CCD class, and Catholics never hear from the pulpit anything to contradict that interpretation. Until now, that is, in Wills’s book.

His discussion of transubstantiation and the Eucharist comprise the most difficult part of the book, certainly for non-Catholics, since it is full of all that esoteric, hocus pocus, insider theological stuff that drove Thomas Cromwell nuts. At the risk of oversimplification, the controversy boils down to the claims you make for the Mass and the Eucharist: is it a sacrifice involving transubstantiation (the prevailing Aquinas view), or is it a meal (the Augustinian view)? Wills sides with liturgical historians who conclude that the Last Supper was not a sacrifice, but an “eschatological [destiny-driven] meal like the other meals and feedings of the Gospels.” It is Jesus’s table fellowship with his disciples looking forward to a fulfilment of his promises, a fellowship repeated over and over in the communal meals of the early Christian community which celebrated their union of faith with each other and with Christ. To support his interpretation, Wills draws heavily on the work of his hero, French theologian Henri de Lubac, to whom his book is dedicated. Lubac published a banned book to support the Augustinian view, was rehabilitated by Pope John XXIII, and influenced the deliberations of Vatican II on the Eucharist to be more favorable to the Augustinian viewpoint.

There are two remarkable omissions in this book. First, as he looks for sources and evidence for his claim that there were no priests in Jesus’s cohorts nor in the gatherings of early Christians, Wills never acknowledges the pioneering research into the form and substance of early Christian worship by the world-renowned feminist theologian, Professor Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza of Harvard Divinity School.

Both scholars tread the same scriptural paths, explore the same scriptural territory, and are very aligned in their aims. Both wish to challenge the received wisdom of the institutional church, but for their own purposes: she to prove a positive, he to prove a negative. Fiorenza’s research proves convincingly that women played active roles in early Christian gatherings which operated under the egalitarian inspiration of the Holy Spirit: a woman may be only a subservient chattel in her domestic life, but was accepted as a contributing equal by her fellow Christians in their “ekklesiae — house gatherings.” Both researchers note the structural and administrative adjustments made by a growing community of believers — men and women could move into roles (as Paul did) like diakonoi, presbyteroi, episkopoi, as dictated by grace, talent, inclination, and need. Wills finds the same democracy and egalitarian spirit in his study of the early communities, a “priestless movement,” with no “church,” no hierarchy, and no priesthood. Both scholars’ research is complementary and mutually reinforcing for a radically different weltanschauung of the origins (both real and theological) of early Christianity.

The second, big, surprising omission in this book is the total absence of any mention of sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests. It remains the big elephant in the room for any reviewer or reader of the book. If you are going to write a book about the uselessness of priests, why not talk about the biggest scandal, and the biggest threat to the priesthood and to the credibility of the Roman Catholic Church in the past century? A lacuna of this magnitude is all the more striking in such a meticulously annotated work.

The omission is obviously intentional: if Wills is compiling a laundry list of the failings of the priesthood, surely the evil of clergy rape and torture of young children would be near the top? Some might even say that the global revelations of Catholic priest criminality has made a book with the title Why Priests? redundant! Why write about the bleeding obvious?

Also, unfortunately, his book appeared in the same month that the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles (RCALA) released thousands of pages of court-ordered documents, revealing the complicity of Cardinal Mahony and his aides in the cover up and perversion of justice for criminal priest employees who abused children for decades. So, questioning the omission of this hot topic is legitimate and unavoidable, and I hope some brave talk show host on the new book circuit will not hesitate to ask it.

I can only speculate that Wills did not want to be distracted from a core argument that is totally built around a scriptural exegesis that disputes and weighs foundational claims for and against a priesthood. One argument might be: if you can disprove the a priore validity for a priesthood in the first place, then a posteriore arguments and evidence for how bad priests can be once they exist become irrelevant. Thus, Wills is not using deductive proofs to construct a case based on 2000 years of evidence to prove the dysfunctionality and non-utility of priesthood ex post facto. Instead, he is arguing from first principles that priesthood is intrinsically wrong, never existed in the first place, and is a false idol of control freaks. Perhaps, then, this book is showing Wills at his Thomistic best, rivalling Aquinas’s “Proofs for the Existence of God” with his own opus here on “Proofs for the Nonexistence of Priests.”

Readers finally get their money’s worth when Wills reveals the 15 tenets of faith that he does believe in. But he can’t resist one final shock to the complacency of the unreflective Catholic by also detailing “disposable items,” like guardian angels, holy water, and Our Lady of Fatima. I can just picture certain audiences rushing for the exits, hands over their ears, horrified at the beloved items of belief that Wills has proscribed so mischievously in his own personal version of the Index.

Is this book a game changer? There are many dispirited Catholics (often called “lapsed” by the Church in order to protect its image as a “never lapsing” institution) who will clutch this book to their hearts because of the tidings of glad joy it brings them. Despite its esoteric theology, it contains enough intuitive truths to convince skeptics that Wills is on to something here. There are also other ardent Catholics who will never forgive Wills for trashing some of their most cherished beliefs and sacraments.

A game changer happens because the latest prophet is far enough ahead of his congregation that the originality of his new ideas is clearly apparent, but not so far ahead that he loses his moonlike pull on their tidal values. Wills is unquestionably a prophet, with stunningly original ideas, but only time will tell if he has forged too far ahead to maintain his pull.

There is, nevertheless one group of local, faithful Catholics who will draw great encouragement and reinforcement from Why Priests?. They are the parishioners of the Vigil Parish resistance movement in and around Boston, who since 2004 have been fighting the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston to prevent it from closing their churches. The trauma of entering guilelessly into unprecedented revolt against their priests and bishops, shocked these novice rebels into a new awareness of their faith. Over time, they have stripped away the clutter, the non-essentials, to arrive at a point where they now practice a simpler, more refined version of their faith in weekly community liturgies of prayer, hymns, communion, and reflections, led mostly by women, without the services of a priest. They are living proof of Wills’s fundamental proposition: why priests?

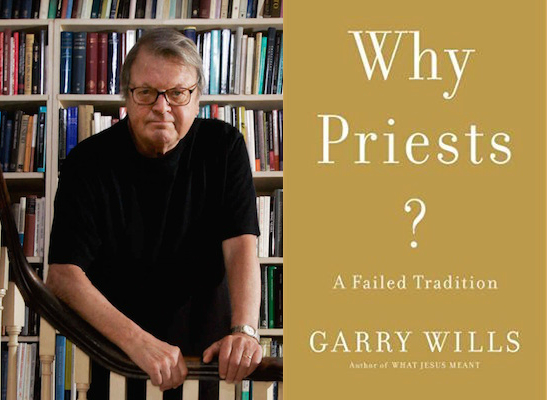

My personal take on this book is that, as Wills the elder statesman nears 80, this apologia is his attempt to tie together years of study, reflection, talk, prayer, into a statement of irreducible faith. This Pulitzer winner, author of Why I am a Catholic, is cleaning house: sweeping out the inessentials, battening down the eternal verities, getting ready for accountability. He owes it to himself to get this off his chest; we the readers are just secondary, but fortunate, beneficiaries of this self-reflection.

As I closed this audacious book, I couldn’t help thinking how nice it would be to have Wills as a grandfather, so he could influence the way the way my children acquire faith and practice it. Ruthless honesty, a faith continuously informed and refreshed by educated reason, perpetual questioning, and a relentless winnowing of the wheat from the chaff.

This is a very brave book by a very brave man. Wills is throwing a gauntlet in the face of the modern Church. It is one thing to criticize the system when you are outside of the system. It is quite another to do so when you are inside the system, and want to remain in the system — but on your terms. You are sure to be treated like a prophet, like Jesus — and killed. Why Priests? Why terminal honesty?

Postscript:

Lest some might think that I am being overly dramatic, read this insider view of prophets from Fr. Richard Rohr, a Franciscan priest, just published on Sept. 13 in his daily meditations:

A prophet is” one who keeps God free for people and who keeps people free for God.” Both of these are much needed and vital tasks. God has been imprisoned and made inaccessible, and far too many people have been shamed and taught guilt to keep us clergy in business. Our job [as priests] became “sin management.” Sadly the laity bought into this negative story line. That is what happens when priests are not informed by prophets.

The priestly class invariably makes God less accessible instead of more so, “neither entering yourselves nor letting others enter in,” as Jesus says (Matthew 23:13). For the sake of our own job security, the priestly message is often: “You can only come to God through us, by doing the right rituals, obeying the rules, and believing the right doctrines.” This is like telling God who God is allowed to love! The clergy and religious leaders, unintentionally perhaps, teach their disciples “learned helplessness.” Thus the prophets spend much of their time destroying and dismissing these barriers and trying to create “a straight highway to God” (Matthew 3:3). Both John the Baptist and Jesus tried to free God for the people, and it got them killed.

So please prophet Wills, buy plenty of life insurance!