With Odd Birds, Ian Harding’s delightful short memoir on bird watching and being famous — a pair of subjects you probably know little about, dear reader, if you’re anything like me — I conducted an odd experiment: take the assignment to write about the book anyway, because why not? See what happens.

“I’m going to say that — for me, at least — the California condor is a metaphor for great, meaningful acting roles,” Harding writes at one point, varying a theme he’s developed in fits and starts throughout the book, an instructive parallel between the pleasures and pains of “birding” and acting. (Harding is best known for his role as Ezra Fitz in the ABC Family drama Pretty Little Liars.) In both pursuits patience matters hugely, of course, persistence, an almost maniacal concentration, and after all that turkey vultures will still be more plentiful than the very rare condors they’re sometimes mistaken for. Turkey vultures are like auditions, Harding writes. “Every time you see one, you think, ‘Oh my God, this could be it. This could be the big one'” — but then the measlier reality sets in. Not a majestic condor, but its cheap impersonator. Not a life-changing role, just a phone that doesn’t ring again.

A rather charming, unfussy meditation on the randomness and luck of an acting life, and a birding life, begins to percolate under the brisk funny scenes that make up this book. Short chapters on what it’s like to audition, live in Hollywood, get recognized (or misrecognized) around L.A., what it’s like to drop everything and drive out of the city to a “rare-bird alert” — this is some of what happens in Odd Birds, and what happens in the reader (if the reader is anything like me) is a kind of slow mental blush, the feeling of being inexorably charmed, the feeling of a widening smile, and a guffaw or three, as the book really hits its stride.

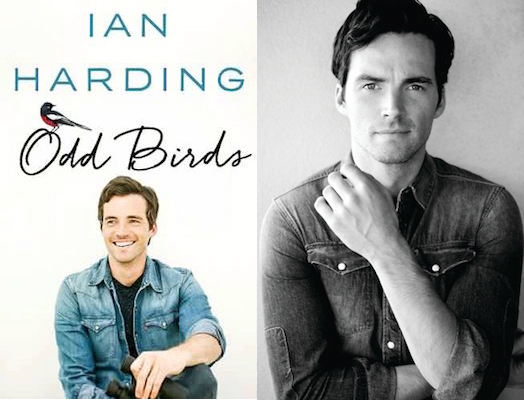

I assigned myself a set of conditions for the experiment: I wouldn’t Google the author, read any of the marketing material accompanying the book, or look up old clips or episodes of Pretty Little Liars, which I’d more than once confused with HBO’s Big Little Lies. (When Harding’s sister pulls up a Google image page of Ian Harding–themed porn, obviously Photoshopped, at Thanksgiving, Harding assures his mother that he “would only ever do full-frontal for HBO…” Then he goes to check on the turkey.) In short, I wanted to accept Odd Birds as a self-contained thing, a private universe unto itself, with its own voice (Harding’s — canny, relaxed, self-deprecating) and its own appeal, which wouldn’t depend at all on Harding-off-the-page, or the fact that, for example, Harding “influences” more than seven million followers on Instagram (that part I did get from the jacket copy, a slight cheat). The only unconjured visual images I allowed myself came scattered throughout the book: a series of black and white photographs of Harding growing up, older Harding with friends and costars, older Harding set against caves, nature trails, ocean — the underrated “outdoor culture” of Southern California that Harding describes and homages so well. And of course Harding’s picture on the cover of the book: an unusually handsome young man posing beneath the title, with a pair of binoculars to hand. He is svelte in a blue jean jacket (Are jean jackets back in? you find yourself wondering) and smiling in that preternatural way actors have of smiling, with a set of teeth and a happy ease that can’t really be taught, and a whiteness to the teeth that’s almost Melvillean in character, semi-divine. Apparently Hollywood casting directors took note of Harding’s bone structure long before they gave him big roles, and no less an authority on beauty than Giorgio Armani once pronounced him “bello, bello,” at a Fashion Week afterparty. If you’d seen the young Harding in Virginia circa 1998, the place and time of his youth, you might have noticed these promising features and suggested a career in acting with the same innocent awe that you’d suggest a career in basketball to a seven-footer.

A preliminary conclusion of the experiment: if actors are the modern-day gods, they trail their camera-created glow, at least in part, from birth, coming down from Olympus with their beauties already beginning to show.

¤

Harding was born into an American military family stationed in Heidelberg, Germany, in the mid-’80s. A few years later, the Hardings moved back to the United States and settled in Virginia, where young Ian started fishing plastic bottles out of the trash to make crude bird feeders. Fast-forward a couple decades, a few years after Harding has graduated from the Carnegie Mellon School of Drama, moved to L.A., and landed his first big role on Pretty Little Liars — his cheekbones have come into their own, his dark pompadour-ish hairdo (contractually obligated, apparently) piles atop his head, he’s honed his acting craft, won awards, and forgotten almost entirely about birds and birding. Then, on a camping trip, a new friend points out a hooded merganser duck out on a lake, and something is reborn. The world is new on the next day’s hike.

I was suddenly aware again of the world in a different but oddly familiar way. Birds were outlined in silhouette out on the water. They were chirping overhead in the trees and in the bushes along the shore. I was paying attention to every sound.

I wasn’t in my head, worrying about work, or thinking about how I needed to watch what I eat over the holidays. It might sound like some hippie California nonsense, but I felt very, very present.

It’s a truism of acting that the lines live as much in your body as in your mouth, but here and elsewhere in the book Harding makes that point come alive. We see how a sensitive birder, alert to wind and sound and every colorful blur as it flushes out of the bushes, is a lot like an actor moving through a scene, sensing and reacting to the currents of feeling in the air, or even the shape of the room. Bird watching is an artistic pursuit, and of course acting is an old and august art form too — but Harding never takes either art form to church, never sacralizes them.

Nor does he get particularly precious about the process of making a book out of his observations and adventures. How did Odd Birds get its start? Apparently Harding’s character on Pretty Little Liars, a high school English teacher, had published a book a few seasons earlier, and Harding had been thinking about writing a book of his own ever since: I wasn’t a writer, I just played one on TV…

Fittingly, Harding’s prose in the book is relaxed, chatty, raconteurial, but every so often a bird flies across the page and Harding flies off after it, lifting into lyricism:

As I turned to look, the movement congealed into the form of a small bird, its tail bobbing rhythmically as it perched out on a boulder in the middle of the water […] You learn very quickly to key in on forms. Size alone can be deceiving — depth perception doesn’t work as well when a bird is set against an endless expanse of blue sky. You look for the little details, like the shape of the crest — and whether it is rounded or squared off. Or even how it flies. Three undulating wing-flaps, and a wide, gliding dip? Good chance that’s a woodpecker.

On one long-awaited trip, Harding sees a bird that looks like “a glowing Cheeto” through his viewfinder — a worthwhile bird, I’d say, if it inspired such a witticism, but apparently it isn’t what Harding and his birding companions have come for. They’ve come to Texas in the spring picturing migratory birds thick as Christmas garlands on the branches, but the reality when they arrive is very different — dissapointing, capricious. A few days earlier and they might have caught a famous feast of birds, but they’ve arrived too late, or maybe the wind has shifted, or who knows.

Disappointment does whisper and sometimes stalk through these chapters — little failures, little regrets — but then the book moves on. One of the main pleasures of Odd Birds is the contagion of resilience and optimism that you can’t help catching yourself. You come out of the experiment with this book feeling a little more present, it’s true — California-sounding, but true.