“Oh no, it’s just a daydream of mine,” says shopkeeper Audrey in the 1983 rock musical Little Shop of Horrors. Her forearm wrapped in gauze, her face scraped and bruised, our tragic heroine yearns to leave her bad-news boyfriend and abscond to the suburbs with the gentle florist Seymour Krelborn. “Not fancy like Levittown. Just a little street in a little suburb. Just me, and the toast-ah, and a sweet little guy.”

Perhaps the queer subtext of Audrey’s ballad “Somewhere That’s Green” could have once been read in earnest. In the 20th century homeownership served as an ideological incentive for postwar capitalism, its stability and prosperity available to those men and women who conformed to the nuclear family unit. The gay man’s relationship to domesticity, and to the society organized around it, was one of violence and disfigurement. The harder he strived to assimilate its aesthetics, as in the short stories of John Cheever and the plays of Tennessee Williams, the more brutal was his outcome. He could “cook like Betty Crocker,” but he’d never look like Donna Reed.

The queer poet Lonely Christopher, 33, came of age in the Great Recession, wherein the postwar promise of homeownership was gouged out by neoliberal austerity measures. A house in the suburbs could no longer justify capitalism, yet it appeared that capitalism needed no further justification — an entire generation could be displaced, saddled with debt, derided as lazy and entitled. For queers, the material deprivation was accompanied by the advent of marriage equality, wherein lobbyists and media pundits instrumentalized the promise of homeownership for political maneuvers. Audrey’s daydream of “a matchbox of our own / a fence of real chain link,” once an expression of genuine queer longing, now pointed to the daydream’s ultimate emptiness. “I had to build a wall / around the pain,” writes Christopher, “but walls don’t work / the very concept of a wall / is insane.”

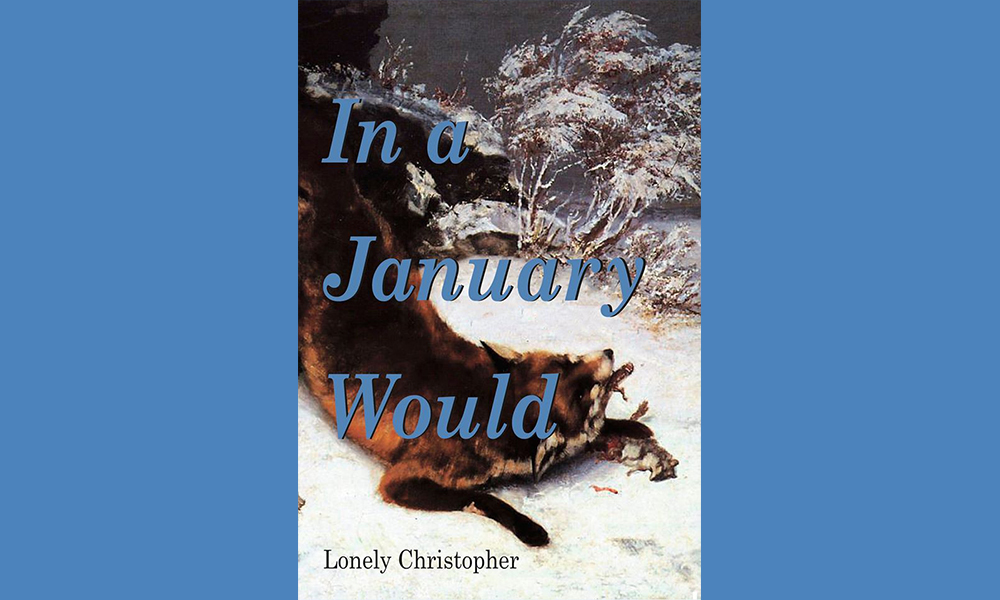

Of course, walls work great for straight people. This might be why Christopher devotes much of his latest collection, In a January Would, to the act of demolition: “Gallons of two percent milk mixed with Ballantine Ale / the adamantine smell of calamitous blood / rushing skyward from the gutters through the floor / rats, millions of them, and forgiveness.” If an image is conjured, the reader can expect the poet to immediately deface it; a serene autumn visit to beautiful Fire Island features “a vial of poppers leaking / into the red wine stain / on the red carpeted floor” and “the strains of a boy’s cum floating in a champagne flute.”

Never does the vandalism register as gratuitous or geared for shock value, nor does it eschew affect or emotion altogether. Rather, In a January Would suggests that under capitalism, vandalism is inherent to the queer experience. It’s wicked and inscrutable, sure, but to ignore it is to reject a crucial aspect of identity. For Lonely Christopher, to leave our world intact is the true act of violence.

The collection opens at the dissolution of Christopher’s relationship and chronicles a bleak post-collegiate year of heartbreak, substance abuse, and precarious living conditions. The poet travels from Paris to San Francisco, Brooklyn to Connecticut, having become an itinerant: “You give me shelter and fugitive boys, their skin / the transient laurels with which I carpet my tongue.” Christopher’s depictions of the seasons, from one winter to the next, provide linearity to a period of the poet’s life in which linearity hardly figures. Formally, the poems assume an ornate Rococo style, perhaps to mimic the refractory experience of homelessness: “Half a year homeless / wasted the year before / there was his hair, the color of praline / like the triumph of Christmas Day.”

Christopher’s work has been acclaimed for its candor and lack of compromise — writing of his debut collection Death and Disaster Series, performance artist Felix Bernstein commended him for “revealing the unthinkably awful without making it palatable (commercializing it, redeeming it or politicizing it).” It’s curious, then, that In a January Would particularly excels at moments in which Christopher interacts with the tropes of neoliberal queer discourse. When he tells his ex-boyfriend “Wonder if it was worth it / not sure by which measure to judge / but I have a stabbing suspicion / all that pain was for nothing again,” he assumes the pose of tragic gay diva, singing platitudes over a disco beat. Likewise, when he recounts those of his generation who “flung their bodies in front of buses or trains / still others clawed vainly at the palace’s skeletal gates,” he deploys the rhetoric of Stonewall-was-a-Riot think pieces, which tend to mistranslate fractured oral history into dubious trivia points.

In the hands of a lesser poet, the passages could succumb to cheap parody or rote attempts at subversion. That would be better than nothing; as Pride Month approaches, we need queer poets to parody and subvert the neutralizing of LGBT rights, even if the work itself is unremarkable. But that is not what Christopher is doing. He goes beyond the obvious, using the iconography of the neoliberal queer movement to demonstrate a scathing point: the rainbows and “Love wins” slogans are woefully out of touch with the day-to-day experience of queer oppression. “I need compensation / for all the time / spent in hells of my own devising,” he writes, “I was amazed to learn then / that it wasn’t all my fault.”

It’s tempting to say that Lonely Christopher is a necessary poet. Indeed, In a January Would expresses the renewed collective desire for a militant queer politics; a crossover is more likely for him than ever. Yet Christopher’s work, in its discipline and authenticity, transcends the dogma and lazy prescriptions of our current moment — it’s not suited for dinner party small-talk, and yet therein is its achievement. Here is queer art that refuses to flatter our biases, that urges us to reconsider what we deem “radical.”

As it turns out, Christopher succeeds where Audrey fails: In a January Would concludes at a country home in the Connecticut suburbs, “amok in the teeming frost.” The gesture might suggest that the poet has reached catharsis, that a broken heart is never beyond repair. But it’s a testament to the rigor of Christopher’s craft, to the strength of his convictions, that he can muster one final act of demolition: “Have you not heard the antsy pleas of less confident / constituents, willing to pay witness to the future onslaught?”