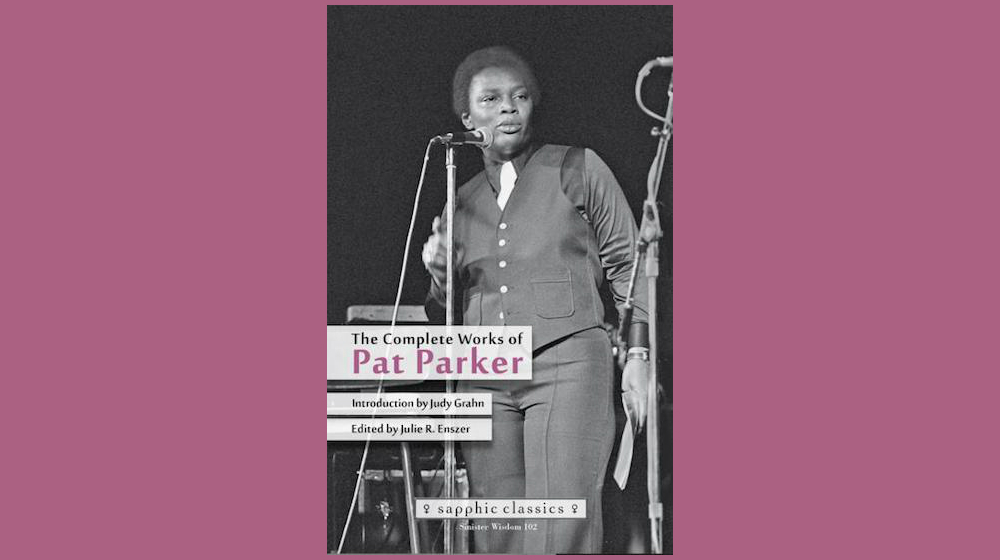

Sometimes it’s hard to engage with a love song when you’re not feeling loved. Sometimes you’re in love and cannot relate to pain. Sometimes your feelings are not sophisticated enough to understand the poem. Perhaps this is why I’ve been in a loop of reading the poetry of Pat Parker for the past two years. The complete volume of her work sits on my coffee table next to a wine bottle I use for water. They say dehydration is the reason to all your aches, so I keep it in the range of my sight as a reminder to drink. When I first laid my hand on Parker’s work, it was not hard to fall in love with a radical handsome woman who casts waves of meanings from her vulnerabilities and strengths. Her queer jokes made me giggle, her love poems fell on me like stones. I continue to return to her poems with no expectations yet feeling safe and assured that I will find something. The more I grow and experience, the more her poems reveal themselves to me.

Parker’s poetics are not sentiments or rhetoric, they are epistemological sounds that can only be received and transmitted on common grounds. When I share her work with friends and lovers, most of them writers or artists, they are quick to judge its aesthetic of ease, flow, vernacular, and rhythm (aka non-elitist black aesthetics); they call it “simple.” The abrupt shortness of her poems is not amusing to them, the absence of titles signifies a lack of craft. I was amazed to find out that such accusations were not new to Parker’s work. In her day, the same judgments were communicated in reviews.

Sometimes, they were even addressed in tributes to her work. In her review of Parker’s Jonestown and Other Madness, Adrian Oktenberg writes: “if Parker’s poetry is simple it is deceptively so. She gets down on paper complicated states of feelings, lightning-quick changes of thought, and she deals with complex issues in language and imagery that any bar dyke can understand… You don’t have to have an education in poetry to read her poems, though the more you have, the better the work becomes.”

Perhaps as Oktenberg suggests, it is the reader that fails to enjoy Parker’s simplicity in non-simplistic terms. The elitist conditions of expecting poetry to come over you as an explosion of images, an exhibit of tools, a disarming breath-taking experience surely make it hard for the contemporary reader to relate to Parker’s poetics — their senses are too sharpened, sanitized, and sensitized for a poet who breathes very slowly through her memories, pains, and loves. Even her contemporary, Cheryl Clarke, has taken fault with Parker’s unpolished writings, and tried to justify it as an intentional move from the author to not lose her “vernacular power.”

What Audre Lorde imagines poetry to be, Pat Parker executes. In “Poetry is not a luxury,” Lorde makes the precise distinction between poetry which our white fathers sold to us as “a desperate wish for imagination without insight” and poetry that our black mothers teach us as a “distillation” of experience that “gives name to the nameless so it can be thought.” Such poetry allows us to accept ourselves, to “train ourselves to respect our feelings” after allowing false accusations of “childishness, of non-universality, of self-centeredness, of sensuality” discourage us from “attempting the heretical actions our dreams imply.” These accusations, on which elitist conceptions of poetry are based, advocate for new ideas over old feelings, though “there are no new ideas, only new ways of making them felt.” It is this very power, of old feelings and new ways, that radiates through Parker’s poems. “Our feelings were not meant to survive,” Audre teaches us, “women have survived. As poets. And there are no new pains. We have felt them all already. We have hidden that fact in the same place where we have hidden our power.” It is no wonder to me that these two poets shared a love too monumental for friendship or romance, fighting the same diseases through their final years. In her poem “For Audre,” Pat writes: “I have known you forever/ been aware that you would come.”

In a foreword for Parker’s Movement in Black, Lorde writes: “Even when a line falters, Parker’s poetry maintains, reaches out and does not let go.” Parker’s verses linger on you, and over the time, become the faces to your feelings — when I am frustrated with white people, I recall “For the white person who wants to know how to be my friend” or “White Folks.” When I want to be compassionate towards them, I read “My Lover is a Woman.” It is that multitude that I find most enchanting about her work and it is also well-grounded in the way she went about her life. Parker was continuously told that she should only be a poet, to focus, to do herself that favor, but in fact she was too big to be only that.

In “Goat Child” and “Womanslaughter,” Parker initiates a motion that will continue to appear in her poems, that of the poet herself and her family and her Texas town. They are not merely ghosts that continue to haunt her and feels obligated to speak to them, or at them, but rather the voices that she borrows to examine a story from different views. The chorus-like voice of the author is louder in her political and womanist poems, sometimes also appearing in a love poem such as “My Lover is a Woman” in which she uses the subject of interracial love to flip through complex experiences of race, gender, and sexuality. In that one-breath of a poem, she does not defend her love for a white woman with rhetoric, nor does she overlook its weight as a burden. She provides a direct reason “I feel good/ feel safe,” and with that safety, she explores the complexity of such love.

My lover’s hair is blonde

& when it rubs on across my face

it feels soft –

like a thousand fingers

touch my skin & hold me

and I feel good.

then/I never think of the little boy

who spat & called me a nigger

never think of the policemen

who kicked my body and said crawl

never think of Black bodies

hanging in the trees or filled

with bullet holes

never hear my sisters say

white folks hair stinks

don’t trust any of them

never feel my father

turn in his grave

never hear my mother talk

of her backache after scrubbing floors…”

By the third part of the poem, I too feel enchanted with her lover: “my lovers eyes are blue/ & when she looks at me/ I float in a warm lake/ feel my muscles go weak with want/ feel good/ feel safe.” Clearly Parker does think about her individual and collective racial experience — she recalls it in such detail, ready to inhabit its complexity. Lorde explains: “[Parker’s] images are precise, and the plain accuracy of her visions encourages an honesty that may be uncomfortable as it is compelling.” Her tenderness, regardless of the theme, is of more effect in the shorter poems. In “Let Me Come to You Naked,” she dreams about a love that is just like her: daring, powerful, intimate, convivial, vulnerable, angry, yet free: “let me come to you naked/ come without my masks/ come dark/ and lay beside you. Let me come to you old/ come as a dying snail/ come weak/ and lay beside you.” It is this companionship that Pat’s praxis of love is rooted in, and can be found throughout her work, sometimes in poems that protest the borderline between love and friendship.

Parker’s poetics help us unlearn how to practice, read, and receive poetry. Just like the author’s multitude, the reader must acquire some. Parker’s poems don’t care for building pyramids, drawing mazes, or packing lines with voices and references. In fact, such free labor has no place in Pat’s praxis. In her letters to Audre, finally published by Sinister Wisdom, Parker speaks over and over about her anxiety toward writing — the agony of not “producing,” while life is happening outside the door. “When it’s going bad, it’s loneliness. When it’s good, it is solitude” she writes to Audre. It reminded me of a terrifying statement by Maya Angelou when she said, “If I wanted to write, I had to be willing to develop a kind of concentration found mostly in people awaiting execution.” Parker was never able to make peace with such state of mind.

Parker believed a poem is never complete; she continued to revisit her poems, publish different drafts, take out some from newer editions, change titles, or give new ones. The unfinished-ness of her poetry becomes a powerful aesthetic against polished art, against a commodification of poetry ready to be picked off the shelves. She surprises the reader, keeps them on check, to draw an ending from a beginning, to become active and imagine connections between a text and the next. Parker’s poetry resembles a song of Oum Kalthoum, 40 minutes long with a lot of repetitions, yet none of it feels like its other. If you read her poems in your head, or in a low voice, at an empty square, or a crowded train, if you read it to your friends, or to a lover, each reading makes the text alive and flowing again. They are the kind of poems that breathe life through the lungs of their readers.