In 2010, Tessa Fontaine’s mother had as big and bad of a stroke as it’s possible to survive. “Don’t hold your breath,” the doctor said. “It doesn’t look good.” Fontaine’s memoir The Electric Woman is about living in the aftermath of this family tragedy. The night of the doctor’s grim prognosis, Fontaine gripped the sink in the hospital bathroom and looked straight in the mirror at her mascara-smeared face. “Human fucking history,” she said to herself. “This is the normal cycle of human history.” Against the throbbing pain shaking through her body, she thought about how people lose their parents and carry on. She thought there must be some innate biological coping mechanism that enabled the numbing of grief. “This is not special,” she made herself say.

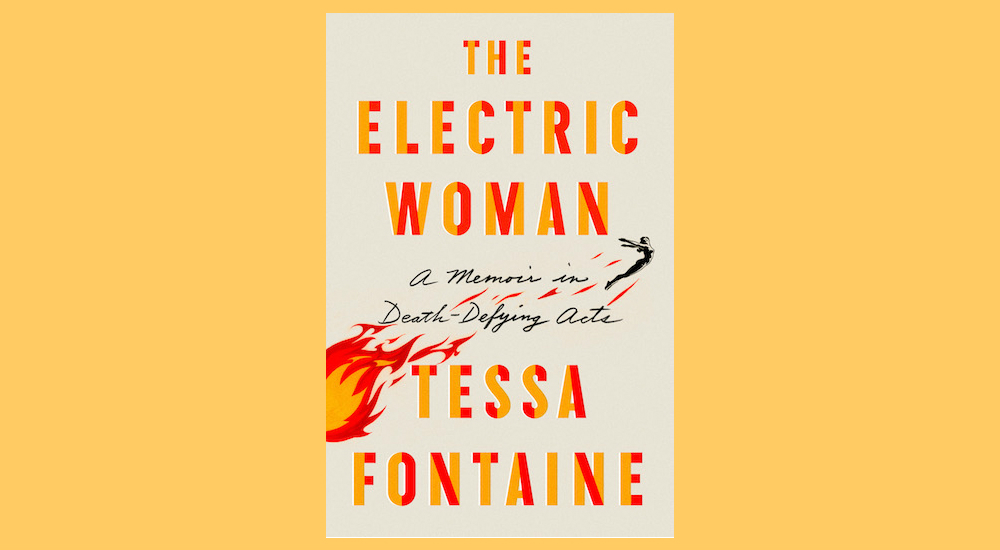

But The Electric Woman is about keeping life special, against all odds. Defying all expectations, Fontaine’s mother, Theresa, survives. After three years of home and hospital-bound battles with recurring strokes, Theresa and Fontaine’s stepdad decide that it’s time to live again. Navigating the complications of a body incapable of speech and scarcely capable of motion, they go slowly and intrepidly to Italy. Adrift and seeking relief from her obsession with her mom’s condition, Fontaine ends up joining the last traveling American carnival sideshow. This path begins as an artistic curiosity. Then it consumes and gives structure to her life.

“Sideshows are where people come to see public displays of their private fears: of deformity, of a disruption in the perceived gender binary, of mutation, of disfigurement, of a crossover with the animal world, of being out of proportion,” Fontaine writes. In her case, it is her internal state that is disrupted and out of proportion. Her pain is enormous and her need for distraction immense. The sideshow provides some relief in the form of fire, knives, and electricity — in endless sweat and toil.

Fontaine participates in a five-month carnival season that features the spectacle of her doing inadvisable things with her body both off- and on-stage. There are no extra workers to set up the transportable city of the traveling fair. The setup and cleanup crew is the same crew that dazzles audiences on the stage, usually with some version of proximity to death. “Wow,” Fontaine’s fire-eating teacher says in admiration the first time Fontaine gulps down flames. “You don’t have many instincts for self-preservation.”

The Electric Woman has spiritual similarities to the memoir and movie The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the story of a French man suffering a major stroke and surviving with locked-in syndrome. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly explores the tension between the prison of an incapacitated body and the spectacle of available to the living mind. Similar to the Diving Bell, while there is plenty that is devastating and harrowing about Fontaine’s memoir, it features a whole cast — extending all the way through Fontaine’s crew of sideshow performers — that are figuring out how to live despite debilitating life circumstances. In the case of The Electric Woman, a traveling fair gorgeously captures this combination of effects. To put on the show, Fontaine and her crew provide and risk their bodies at every stage. The work is bleak, repetitive, and dangerous, and the pay is minimal. But there are moments — at night when the midway is lit up and the Ferris wheels and bumper cars are sparkling — when the effect is transcendent.

Fontaine’s mother is a model for her daughter in terms of pulling this off. When Theresa was young, she used to perform for people on the beaches of Hawaii. She used to climb on top of another surfer’s shoulder and wave regally toward the audience. “She performs fearlessness,” Fontaine writes. Like her mother quivering atop a tandem surfboard, Fontaine learns that the spectacle emerges from the concrete reality. You eat fire by eating fire. Fontaine will do it many times a day for many months. “When I begin to doubt that I can pull this off, I stop and think of her,” Fontaine writes. “The only way to do it is to do it. There is no trick.”

Fontaine and her mother are both dreamers and performers, but their lives are also very different. Heartbreaking stretches of Fontaine’s memoir wrestle with the pain of reconciling past wrongs in the light of present tragedies — of not just failing to say I love you, but not saying anything at all. Fontaine remembers sitting with her mom in the car outside a fancy high school where 13-year old Fontaine was about to interview. “I never had a chance like this, you know,” Fontaine’s mom says. “I let people tell me I wasn’t smart my whole life and I believed them and it almost destroyed me. But you. Go show them. You are very, very special.”

Much of the magnificence of The Electric Woman rests in the realization that almost anything can be made beautiful, at least for a time. Fontaine’s stepfather, who cares for his wife with endless compassion, is another of the miraculous performers in this book, slowly moving Theresa’s motionless and fragile body around the world. Early in the story, he tells Fontaine about a secret spot in Rome he found when he was 19. He bought some dope from a guy in a back alley and stumbled into this garden with broken sculptures. He wants to find that place again and show it to Theresa. Or, while sorting a four-month supply of anticonvulsants, antihypertensive agents, osmotic diuretic, antibiotics, pain management medications, fibers pills, and vitamins, he says, “I just want to see her face, seeing the bridges in Florence.”

As one of Fontaine’s sideshow compatriots tells as she’s just starting: “Don’t worry. Performing the acts is the easy part of making it out here.” It’s not setting yourself on fire or using your body as an enormous electric channel that’s hard. It’s not arriving in Rome or even getting on the boat. It’s getting up each morning and transforming a bleak daily reality into something special. Fontaine and her mother are born performers. So that’s what they do.