With film adaptations, there is a tendency for the source material to overshadow the director and for failures of fidelity to conquer the critical conversation. On that tendency, Andre Bazin wrote that “literal translations are not faithful ones” and to adapt a work for the screen requires the director to dream the story over. (I will never forget my first encounter with screen adaptations, Holes, though loyal to Louis Sachar’s words, cheapened into an exasperating and overdetermined entertainment.) In Drive My Car, Japanese director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi pressurizes the foundering emotional isolation in the Haruki Murakami story on which it is based to create an absorbing and discursive melodrama about communication, passivity, and regret.

Best known for his five-hour epic Happy Hour that improbably recalled both Sex and the City and the films of Jacques Rivette, Hamaguchi’s chief cinematic concerns include the intimacies and banalties of life, the enigma of our impulses, and the nature of acting and roleplay. Though lengthy, his films are highly digestible. Their durational nature, far from soporific challenges, affords him the breathing room to display his craft and cast a spell: a bewitching long-con predicated on delicate atmospheric shifts. His sleight of hand yields seismic consequences in the characters’ lives that reveal the confused logic and ominous rationale of human behavior. This, in some ways, makes the director an appropriate candidate for transposing Murakami’s plainspoken fiction — which also finds the overlap between the surreal and candid — to the screen.

The original story, from 2014 collection Men Without Women, concerns a stage actor with a double blind spot: a literal one that requires him to have a personal driver, and a figurative oversight that allows his wife’s infidelity to elude him. After she dies, he befriends his wife’s ex-lover — who doesn’t know that he knows about the affair — in a futile effort to excavate her motivations. Taking place primarily in the car, the tale unfolds essentially as a flashback: the actor gives an accounting to Misaki, his young driver, as she chauffeurs him to rehearsals for “Uncle Vanya.” One of Hamaguchi’s primary changes is to reconstruct the movie in the present tense, which thrusts us into a more active mode of viewing.

Oto, the wife, has only recently passed, and the actor, Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) now pulls double duty as director of the Chekhov play, a multilingual production with international actors. The languages spoken include Tagalog, Mandarin, and Korean sign language. While Yusuke still suffers a slight glaucoma, the driver (Toko Miura) has been sanctioned as a workplace requirement not a medical one, and her presence disturbs the neutral harmony of his car, which serves as a liminal third-place. Hamaguchi and his cowriter Takamasa Oe have fashioned a backstory for her, unlike Murakami, and cut away some of the story’s underlying misogyny. The strange kinship between the actor and driver in the book was based on the former’s biased skepticism of women’s vehicular intuition.

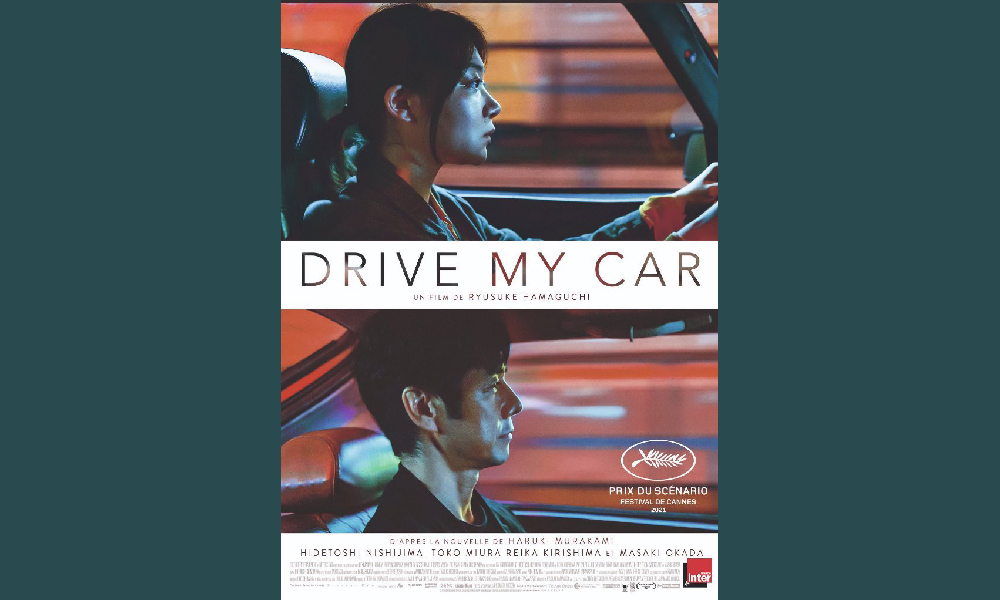

Some changes are necessary for visual fortitude: the car, a yellow Saab 900, is now conspicuously red, chosen precisely to pierce the monotony of the highway. Throughout the film, the camera finds unique ways to film the car, whether as a gliding entity from above or by widening the depth between two passengers within.

Other tweaks, though, wring out ambiguity to heighten the emotional stakes and reverberate throughout the film. In a stroke of fortune or fate, Oto’s young paramour, named Koji (something of a brash himbo, brought to life by Masaki Okado), auditions for the play. Yusuke hires him, and goes one further casting the young man as Uncle Vanya. The intentionality of their meeting stokes questions about Yusuke’s motives and adds an unexpected edge of psychological (that is, vengeance-tinged) suspense. In the book, Yusuke had “something approaching affection” for his tenuously begotten new friend, who in turns sees only “the kind of stillness you might expect from someone who had recently lost his wife of many years. Like the surface of a pond after the ripples have spread and gone.” Yusuke’s demeanor in the film, as played by Nishijima though, is more of an umbra of brittle curiosity and severity.

The minor circumstances of Oto’s death have also been altered. She suffers an unexpected medical tragedy in the film, rather than a slow demise from cancer, which arrests Yusuke from the opportunity to confront her duplicity, cutting him into a more tragic figure. By collapsing fictional time and modulating small details such as these, Hamaguchi sharpens the edges of the characters’ motivations and eventually transforms the emotional tenor of Murakami’s book, a detached pond of sadness, or a rain “drenching the world in a cold chill,” into a sweltering flame of grief.

The film incorporates other elements from Men WIthout Women, ranging from cerebral and small that fit Hamaguchi’s modus operandi. Oto’s predilection for sex and storytelling is borrowed from “Sheharzade,” and the notions of language as part of identity and disguise, as exhibited by new characters like an ethnically Korean stagemanner slipping in and out of Japanese, speaks to “Yesterday.” Meanwhile, “Uncle Vanya,” a mere contextual detail in Murakami’s story, is a spectral presence in the entire book and a colossal one in the film, where Hamaguchi communes with the Russian playwright’s themes. Sonya’s famed monologue about knowledge and ignorance is echoed not only in “Drive My Car“ (the actor’s self-stated core principle: that knowledge is better than ignorance), but by other male characters in other stories (the man who receives a phone call from an old lover’s husband in the final story “stuck somewhere in the middle, dangling between knowledge and ignorance”), drifting around in a purgatory bereft of women.

The integration of Chekov adds not only a meta-textural resonance, but also demonstrates how art can act as a bulwark against emotional stasis. The play’s dialogue is an extractionary balm, which becomes a sort of sutra as one character describes, particularly when read aloud without affect as Yusuke instructs them to do. He is tailored into the addled-mode of Vanya hemmed in by circumstance and complacency, and what he is unable to confront and say out loud, he speaks through one of Chekov’s designs. And not just him, but others characters well, including the discreet homewrecker and the driver experiencing her own past loss. Yusuke asks his actors to yield to the text, and Hamaguchi expands it, Chekov’s and Murakami’s, to weave his own tapestry of anguish and grief — one that comes with healing, and not just for men without women — but for people without people.