A couple sits, a third person in their presence. The dinner feels a bit uncomfortable, the conversation flows slower, there seems to be something unspoken. The source of tension is obvious: the extra person.

But what happens when the feeling lingers, even when the third has left?

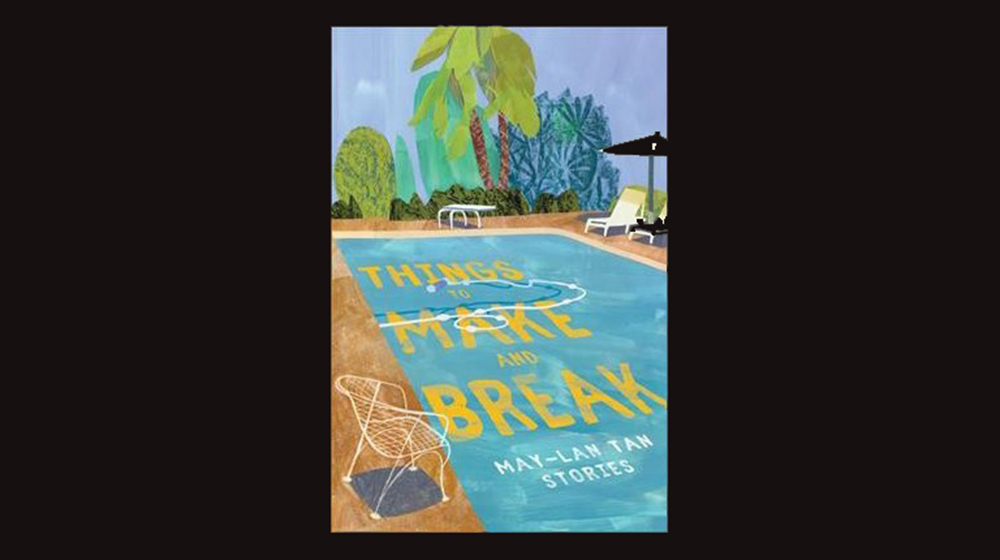

Things to Make and Break, May-Lan Tan’s collection of short fiction from Coffee House Press, explores this idea: the often unseen or unnoticed third element in the complicated relationships one weaves. It makes this a collection worth not only reading once, but twice. Like a third presence in a room, the act of rereading transforms the stories once again.

Each of the 11 pieces explores a different kind of third element, from the obvious, like infidelity, to subtle, the death of a person one has never known. In “Legendary,” a woman is fascinated by her partner’s stories about his exes and goes searching for one in particular: Holly, a trapeze artist who suffered a serious fall. The unnamed protagonist becomes entangled in the desire to know more about her partner’s former lover.

She begins to watch Holly from afar, staking out her apartment and following her to the Korean market down the street where she catches a glimpse of the woman’s tattoo. The woman goes home to trace it on her arm in Sharpie, copying it from an old naked photograph of Holly her partner keeps on file. She smokes a cigarette as mimicry. Sometimes, it’s easier to get to know someone else than to know yourself.

Later, following Holly, she discovers that she is a street performer. Holly pretends to be a mechanical doll, only working when change is put in her piggybank. As tourists watch unimpressed, the woman says, “I feel like telling them who she is and what she is capable of.”

The attachment becomes something to hold on to as her relationship with her partner ends. She’s still living with him as he starts to date someone new. She asks what story he’ll tell about her and he says, “Probably about how you kill bees, using your hands.”

Earlier in the story, the unnamed woman is noted to work as a courier, and in her free time takes karate, drawing classes, Italian. Her partner wonders why she bothers with these classes if she could take a “real course” to get a degree. She has to remind him she already has one. The truth is laid bare; he’s just another man who doesn’t value the complexity of the women who enter his life. But it’s as if she needed the story of Holly to see, with honest eyes, her own position in her relationship. The disappointment is palpable.

Despite the often negative outcomes of a third party’s presence in the relationships depicted, there is often a sense of the relief when they end. A sense that it isn’t worth it to keep fighting anymore, because the beauty is the understanding and knowledge that comes from accepting a different outcome than one may have hoped for. That instead of being angry or trying to change things, it’s easier to accept the pain that comes from the present knowing it might help you in the future.

This is particularly true in “Candy Glass,” the longest piece in the collection, formatted like a movie script. Actress Alex and her stunt double, DC, develop a relationship that moves from platonic to romantic while on the set of a film. Each day, their lives intermingle as one follows the other. Through conversation between takes and after the day is done, they realize that their lives have overlapped previously. DC had been introduced to Alexa through her famous, stunt-double father on a set years ago and developed a crush on her. She had admired her for being openly lesbian, feeling that she could be out too. Soon after, they sleep together.

But their lives separate. DC flies back to Los Angeles before the film is over. Alexa is alone again. They try to reconnect over dinner, try to have sex again, but whatever was once there is gone. DC does not want to be the person Alexa knows her as. She expresses a desire to cut all ties with her family and marry a man, becoming a suburban mother.

Alexa takes on a new project, an independent film based near her East Germany roots. Though she and DC have no further contact, save for one voicemail from DC, Alexa describes in a voiceover how her relationship with DC continues internally. A voiceover from Alexa details how she’s watched all of DC’s movies, trying to find her. She pictures her in relationship with divorced high school science teacher where they go camping and see movies.

Even though DC’s relationship is only fictional, the idea is powerful enough to alter her feelings. Alexa feels a longing for something that doesn’t fit into the narrative DC has written for herself: a scenario where they could be together. The loss of the imagined relationship feels just as intense as the loss of a real one.

These stories of heartbreak and missed connection can be difficult to stomach. How can something as amazing as the connection between two humans also be so violent and painful?

Tan’s poetic style softens the blow. At the beginning of “Julia K.,” in which two tenants form an eerie bond, this brilliance appears: “Language, as she deployed it, was neither a line cast nor a bullet fired. It was a catholic mechanism: the sharp twist of a pilot biscuit into the waifish body of a christ. A word placed on her tongue, became flesh. One night it was almost morning, I could almost see her, every sentence a necklace she was pulling out of her mouth, tangled in smoke.” That description could just as well explain Tan’s own writing.

It’s hard to read something that seems to say love is merely hardship with little possibility for return. Things to Make or Break is no escapist literature, but that does not mean it’s devoid of pleasure or fulfillment. Tan writes, “To me, other people used to be a show that was on sometimes, like fish at the aquarium, and now I could feel everyone around the world at once, in painfully exquisite detail.” This book turns your senses so sharply it’s hard not to feel thankful for it — how is it possible to have missed these moments before?