I’ve been thinking a lot about sleep lately. And it’s not due to those trendy articles touting proper sleep hygiene or some TV doctor’s claims about the benefits of getting a solid eight hours. Instead, I’ve been contemplating slumber as an act of defiance, a personal protest against society’s hyper-ambition and its narrow view of how one should live.

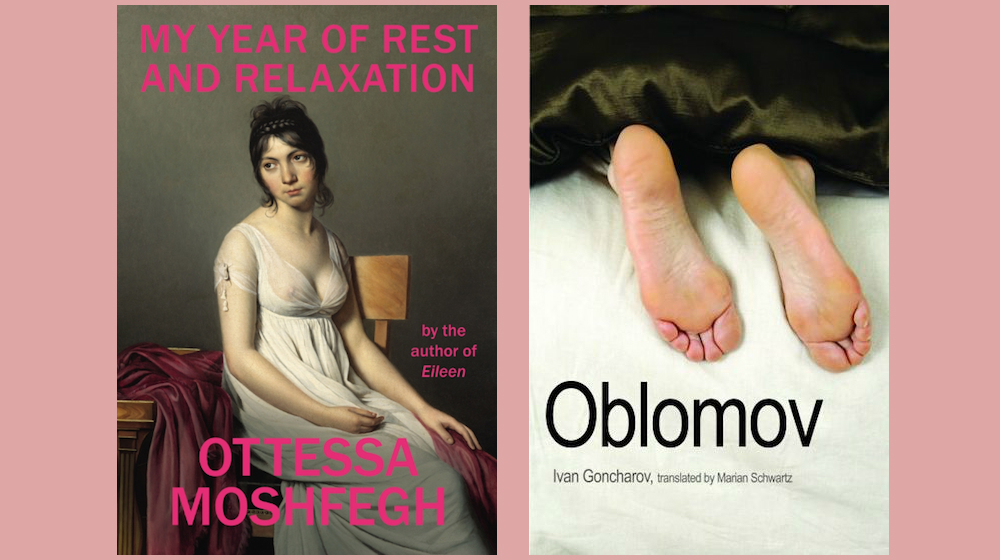

My inspiration, you might have guessed, is Ottessa Moshfegh’s bold new novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation as well as another, much older novel that also features a sleep-obsessed hero: Ivan Goncharov’s Russian classic Oblomov (1859). Although the settings of the two novels could not be more different—modern-day Manhattan (Moshfegh) and 19th-century St. Petersburg, Russia (Goncharov)—the parallels are striking.

Both Moshfegh’s unnamed narrator and Goncharov’s eponymous Oblomov reject the urge to take-up the petty concerns and ambitions that propel everyone around them. Sleep is their weapon of choice.

My Year’s hero gives us a first-person account of her plan to undergo a months-long period of pharmacologically-induced sleep. 24, single, and living alone in Manhattan, she’s just been sacked from her job as a receptionist at a swanky modern art gallery where her only pleasure was stealing hour-long naps inside the supply closet. She now prepares to enter a prolonged state of somnolent “nothingness,” aided by the mountain of pills prescribed by her absurdly incompetent psychiatrist. Here Moshfegh departs from the usual narratives of substance abuse. Her protagonist does not swallow pills as a conscious or subconscious means of self-annihilation; rather, her drug consumption is a method of self-preservation — an intentional hiatus from her life rather than the destruction of it.

I thought life would be more tolerable if my brain were slower to condemn the world around me.

I knew in my heart… that when I’d slept enough, I’d be ok… bolstered by the bliss and serenity that I would have accumulated…

On the other side of the world and almost two centuries prior, Iliya Ilich Oblomov, too, is devising a plan. A young member of Russia’s landed gentry, he has inherited his childhood home — an old family estate in the country — along with its three hundred serfs. Oblomov hopes to create a program to improve the management of his inheritance. Every day he contemplates various iterations of a plan while comfortably recumbent within his St. Petersburg apartment, far away from the place and the people whom his feckless ideas are meant to benefit.

As soon as he rose from bed in the morning, after his tea, he would lie right back down on his sofa, prop his head on his hand, and ponder, sparing no effort, until, at last, his head was weary from the hard work and his conscience told him enough had been done today… (Translated by Marian Schwartz, 2008.)

Apart from these well-intentioned musings Oblomov’s sole desire is to lounge about, frequently succumbing to sleep, regardless of the time of day. Convinced that life should be “nothing other than an ideal of tranquility and inaction,” he stays withdrawn from what he sees as the pointless rush of life, shunning all interest in the soulless ambitions of his peers. When confronted about his lifestyle by his closest friend Stoltz, Oblomov confesses that he is simply, “too lazy to live.”

Stoltz is a striver, full of ambition and constantly seeking to improve himself. Much the same can be said of Reva, the narrator’s best friend in My Year.

Reva was partial to self-help books and workshops that usually combined some new dieting technique with professional development and romantic relationship skills, under the guise of teaching young women “how to live up to their full potential.” Every few weeks, she had a whole new paradigm for living, and I had to hear about it.

I had chosen my solitude and purposelessness, and Reva had, despite her hard work, simply failed to get what she wanted — no husband, no children, no fabulous career.

Both Reva and Stoltz are vitally engaged with the world and seek society’s affirmation. Their conventional ways of thinking about themselves and their social standing diverge sharply from those of Moshfegh’s narrator and Oblomov. The contrast provides rich fodder for our heroes’ deep cynicism about society’s hypocrisy and superficiality and their disillusionment with a world in which these attributes are the norm. Oblomov complains to Stoltz:

The perpetual running to and fro, the perpetual play of petty desires, especially greed, people trying to spoil things for others, the tittle-tattle, the gossip, the slights, the way they look you up and down. You listen to what they’re talking about and it makes your head spin. It’s stupefying… It’s tedium. Tedium! Where is the human being in this? Where is his integrity? Where did it go? How did it get exchanged for all this pettiness?

Similarly, Moshfegh’s narrator confesses:

I had thought that the Upper East Side could shield me from the beauty pageants and cockfights of the art scene in which I’d ‘worked’ in Chelsea. But living uptown had infected me with its own virus when I first moved there. I’d tried being one of those blonde women speed walking up and down the Esplanade in spandex. Bluetooth in my ear like some self-important asshole…

On the weekends, I did what young women in New York like me were supposed to do, at first: I got colonics and facials and highlights, worked out at an overpriced gym, lay in the hammam there until I went blind, and went out at night in shoes that cut my feet and gave me sciatica. I met interesting men at the gallery from time to time. I slept around in spurts, going out more, then less. Nothing ever panned out…

In the face of the pervasive pressure to conform to societal expectations the protagonists accomplish something brave and extraordinary — they hold a steadfast resistance, shunning life’s rushing tide of demands and expectations. These characters seize the refuge of sleep in order to find their inner selves. They need the quiet and tranquility that they can find only in a state of restful solitude in order to foster what their souls crave: an interior life that is capable of seeing and appreciating the world around them, of experiencing genuine feeling and sincere empathy for others.

But while sleep is the protagonists’ common instrument of defiance its repercussions are markedly different for each. Sleep heals Moshfegh’s narrator, dissolving the adhesions that had kept her “stuck” in despondency. Following her period of drug-induced sleep she feels a daily appreciation for the unexceptional things that she encounters. She begins a new phase of her life, one in which she is fully present and part of the world around her.

I breathed and walked and sat on a bench and watched a bee circle the heads of a flock of passing teenagers. There was majesty and grace in the pace of the swaying branches of the willows. There was kindness. Pain is not the only touchstone for growth, I said to myself. My sleep had worked. I was soft and calm and felt things. This was good. This was my life now.

Oblomov’s somnolent lifestyle, on the other hand, atrophies his existence. He becomes increasingly despondent and isolated, his friendships are fewer, his experiences ever narrower.

[H]e quietly and gradually fit himself into the simple and wide coffin of the remainder of his existence, a coffin made by his own hands, like the elders in the desert who, turning away from life, dig themselves a grave.

Each of these contrasting outcomes feels completely authentic. While Oblomov finds it impossible both to nurture an inner life and be fully engaged with the world, Moshfegh’s narrator demonstrates, ultimately, that one can thread the proverbial needle. And so, My Year concludes on an unexpected but emphatic note of hope, an affirmation that even in our noisy, disruptive, and false world grace does exist, ready to be awakened in a mind and spirit sated by quiet, restful contemplation.