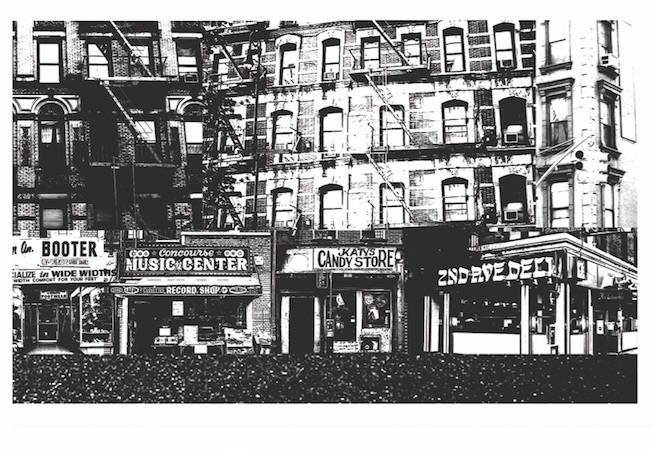

When you read Tina Cane’s Once More with Feeling you will scratch your head and say, “What the fuck?” You might not actually say, “What the fuck?” But I did. The question gave rise to another one: “What took so long for someone to publish this book?” But don’t waste too much time on questions; return to the poems and read them again — once more, with feeling. One way to read this book is to listen to Lou Reed’s 1989 classic record New York. The book is a Romeo and Juliet of Hell’s Kitchen. That is to say, it is New York — a New York that rolls around in the late 1970s then falls straight away into the 1980s. If you were coming of age in New York at that time, be it in Queens, Manhattan, or Canarsie, you will get this book. It’s part of your DNA, already in you, even though you had no idea it was there. It’s some back page of your personality, which you might have filed away, might have forgotten about, but once you step inside Cane’s vision, boom, there you are, hopping into the L train at 14th Street and headed into Williamsburg. It’s 10th Avenue, stinking and brutal, up in your eyeballs. You know it. You will know it. Delicious, like a mile-high pastrami sandwich from The 2nd Avenue Deli, or the rear corner of Gus “N” Bernie’s Candy store, with all those fantastic comic books.

But, here’s the thing — and it’s a real thing — if you have never been to New York, in any era or time, if you have never smelled its Hudson River down at the piers on the West Side, or been underground at 86th and Lex in August, the underground’s dirty boulevard of rats, these poems are still a part of your DNA. For all their specificity, and perhaps because of it, they are authentically universal in their humanity — full of feeling and fit for any time. Once More with Feeling is New York, Hell’s Kitchen, bodega, checkered cab, 18th Street, but it is also love, and heartbreak, and mom, and dad.

But I’m a New Yorker, and I can’t help finding special resonance in poems like “A Minor History of the East Village”:

Maybe you knew a kid who booked through Tompkins Square

on his Schwinn and came out the other side without the bike

and in his socks never mind he wasn’t buying drugs this the price

of his stupidty…

Knew him? I was the kid. Not stupid, but definitely “booking” on my Schwinn when I saw my boy Eric R. coming home from his piano lessons through CPW. Someone had taken the Pumas right off his feet on 94th. When I met him mid-block, he looked like a truck had murdered his heart. These were the days of joy and horror, which Cane captures in lines that are vernacularly lyrical and blunt.

There is the motif of family, too — of father (who drove a cab) and mother. In the second section of the opening poem, “Sirens,” Cane writes:

To tell you my dad drove a cab for forty years kept a red bean he got

from an Ethiopian guy in the back pocket of his Levi’s to ward off hemorrhoids

that he wrote me notes throughout the night on the margins of his fare sheet stuff

like “eat yogurt for osteoporosis” that he listened to Tosca for another life in which

he didn’t have his foot on any pedal didn’t ever have to chase a punkass kid to get his

money back then end up buying the kid a sandwich to tell you that he was a Jewish guy

from Brooklyn what the fuck he’d pound the wheel cut off cut short

Nothing here, however, is “cut off cut short.” Cane’s voice is full and robust and magnetic. The raw tenderness is the collection’s heart, always pulsing, a kind of pure piece of denim ripped from her father’s Levi’s, which will never let you forget where you came from. And Cane always returns to where she came from, as she admits in “Nocturne: Hell’s Kitchen”:

I came back to the geography of it Manahattan: land of many hills eastward origin of my arrival

crossing Ninth Avenue under the Capeman’s shadow past the Westies and their bucket of blood

I come back to a sky charged with volcanic ash orange moon over the rooftops of 45th st heat

and people’s voices rising from sidewalks through the bars of our fire escape

through the rails of my crib back to my mother’s black hair draped like a curtain

from where she lay on her red velvet bedspread eyes shut in the crook of her arm hypnotized by loneliness the solemn authority

of her resolve a topography I come back to

In the last of the book’s four sections, the poet finds herself in Madrid, Algeria, Prague, but wherever she is, there is always New York. A New York of one, of family, of history, of possibility. In shorter lines, Cane writes:

…New York I

was always possible in you

despite your tendency to ruin me

for everything from grass

to the pleasures of snow

I know

Cane is clearly a craftsperson with attitude. There is nothing better than attitude. You know where she got it, too — from her father, her mother, from the tenements and gangs that roamed the streets of Hell’s Kitchen. You can’t mess with her, her New York, her voice. These are the kinds of poems that make you want to crawl into the back seat of her father’s checkered cab and haul ass up 10th Avenue; drink scotch, neat, with her mother; sit on a stoop on 46th Street, mid-August, and let the sirens just break your heart into pieces. Once More with Feeling is a book of the most beautiful soot and grime. Wherever you come from, its family is your family, its city is your city.