Near an enlarged photograph of his beloved great-grandparents that he kept above the work table in his sparsely furnished studio, the artist Romare Bearden (1911-1988) had also pinned the preface to William Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads. Wordsworth’s preface, hand copied by Bearden, reads, “He is the rock of defense of human nature, an upholder and preserver, bringing everywhere with him relationship and love.”

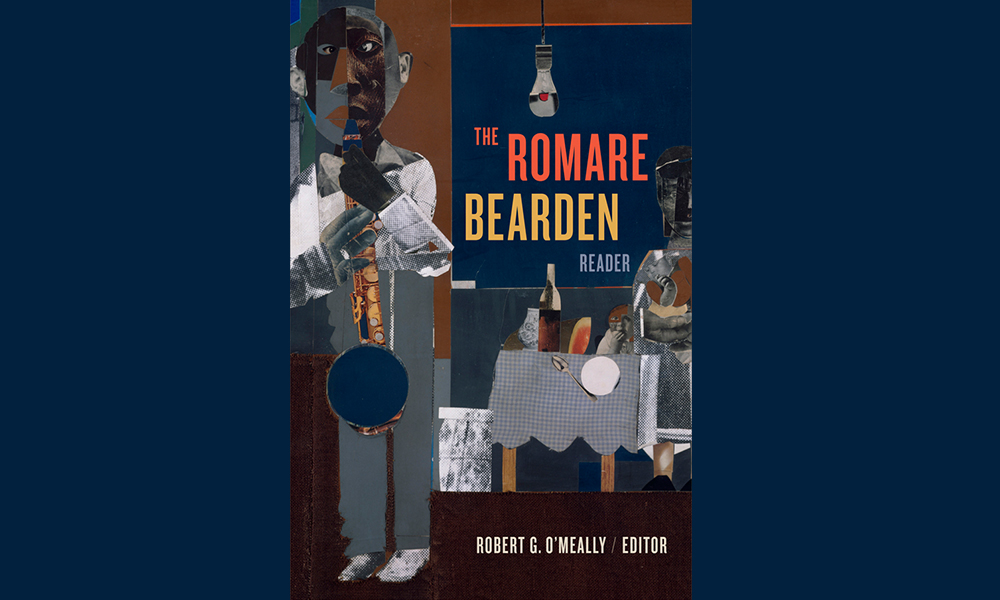

Bearden, one of the great artist-humanists of the 20th century, labored beneath the image and the words each day as he pieced together the collages on themes of urban and rural African American life that would make him a nationally recognized figure. Bearden’s devotion to his subjects and his craft, his drive to collaborate with other artists, and his unerring compassion for his fellow man, characterized his life and career. Two recent books — The Romare Bearden Reader (Duke University Press, 2019), edited by Robert G. O’Meally, and the catalog of a current Bearden exhibition at the High Museum in Atlanta, “Something Over Something Else”: Romare Bearden’s Profile Series (University of Washington Press, 2019) — elucidate Bearden’s enduring legacy.

The Reader and the catalog were released in anticipation of the opening of “Something Over Something Else,” an exhibition of the Profile series at the High Museum of Art, which runs until February 2, 2020 before moving to the Cincinnati Museum of Art on February 28. In response to being the subject of a New Yorker profile by Calvin Tomkins in 1977, Bearden created his own “profiles” of people and places of his youth in Charlotte, Pittsburgh, and New York. By that time, Bearden, who had retired from a 30-year career as a social worker in New York’s Department of Social Services, had already had a solo show at MoMA (the first black artist to do so and the last for several decades). The show exhibits 33 of 47 collage paintings Bearden completed for the two Profile exhibitions at Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York City in 1978 and 1981, respectively. The Profile series features collages set in the 1920s and 1930s in three settings, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Pittsburgh, and New York, where Bearden and his family variously resided during that formative time in the artist’s youth.

Bearden expresses the complexities, passions, and layeredness of life through the lens of African American experiences. The intricate Profile collages are among the most profound representations of African American families, communities, and culture that exist in American art. Pieced together with care, concern, and no small degree of love, the collages, like School Bell Time and The Allegheny County Colored Baptist Sunday School Picnic and, especially, Farewell Eugene, demonstrate Bearden’s genius for gesture, movement, and depth of feeling. Out of newspaper scraps, fabric strips, paint, glue, book clippings, and other materials, Bearden fashioned an entire world of characters, hopes, and dreams.

Until this year, the Profile series remained an understudied and overlooked period in Bearden’s long career. Last year’s widely reviewed biography of the artist, Mary Schmidt Campbell’s Romare Bearden: An American Odyssey (2018), only glances at the Profiles. The raison d’être for the Profile series exhibition was the High Museum’s 2014 acquisition of Bearden’s Profile/Part II, The Thirties: Artist with Painting & Model. The nearly 4’ x 5’ collage painting — the largest in the series — “was a transformative acquisition,” Stephanie Mayer Heydt, Margaret and Terry Stent Curator of American Art at the High, said in an interview with Forbes.com. Heydt continued,

[Artist with Painting & Model] is a major picture — the only proper self-portrait that Bearden makes in his career. So the work is a real statement about Bearden, by Bearden. He has surrounded himself with emblems of his inspiration — African art, Byzantine art and Renaissance traditions, blues and jazz, Matisse, and even his own pictures. Through this picture, Bearden is claiming his place in art history.

Nearly 32 years after his death, Bearden’s interpreters — led by Heydt and O’Meally, who co-curated “Something Over Something Else” — have established Artist with Painting & Model as one of Bearden’s finest.

It is a testament to O’Meally’s Reader and the catalog that Bearden’s own words and insights are given considerable attention. The exhibition title, “Something Over Something Else,” is taken from a phrase Bearden used in conversation with Calvin Tomkins to describe his complex collage process. The catalog not only publishes the full text of Tomkins’ article, which features the conversations with Bearden, but also Bearden’s own reflections on Part I of the series.

The Reader, which predates the catalog by a few months, reprints much of the best writing by and about Bearden. O’Meally includes Tomkins’ article in the Reader, as well as eight standout examples of Bearden’s writings on art (including dozens of previously unpublished diary entries from 1947-49). Moreover, O’Meally chose for the Reader 17 essays about Bearden by some of the US’s leading writers such as August Wilson, Toni Morrison, Ralph Ellison (two essays), Albert Murray, John Edgar Wideman and Elizabeth Alexander.

Writers have always recognized the literary qualities of Bearden’s works. When Bearden was in his mid-30s, he visited William Carlos Williams who immediately recognized that Bearden was trying to humanize abstraction. Even then Bearden’s use of color surpassed any of the paintings Williams had collected, the older artist said. To August Wilson, Bearden’s collages were like listening to “an aria of faultless beauty and unbridled hope.” Wilson’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone was inspired by Bearden’s Mill Hand’s Lunch Bucket, featured in the Profile series. Toni Morrison recalled how Bearden once surprised her and sent a portrait of the character Pilate in her novel Song of Solomon. The painting went “far beyond my word-bound description,” Morrison writes. Maya Angelou, Derek Walcott, and Albert Murray were some of Bearden’s distinguished collaborators.

In 1978, Bearden is said to have walked into Cordier & Ekstrom just before Profile/Part I opened and chalked captions for each of his collages on the gallery walls in his calligraphic hand. For example, Bearden’s “Daybreak Express” (1978), in which a high-balling train can be glimpsed through the window of a beautiful woman’s room, has for its caption, “You could tell not only what train it was but also who the engineer was by the sound of the whistle.” The exhibition takes a cue from the original Cordier & Ekstrom shows and reproduces Bearden’s enigmatic captions next to each of the collages. These handwritten captions, not unlike the Wordsworth quote Bearden had written out and placed near the photograph of his great-grandparents, fostered new and added dimensions to the works.

The story of the texts springing Minerva-like from Bearden’s forehead is reminiscent of the charming legends collected in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists. It is most likely that Bearden memorized each collage’s caption after workshopping them with the writer Albert Murray. Murray scholar Paul Devlin, in an illuminating essay in the High Museum catalog, “Two American Modernists, Second-Person Singular: Albert Murray’s Words in Romare Bearden’s Profiles,” clears up years of speculation on the Murray-Bearden collaborations (which also included the naming of Bearden’s pictures). Devlin reads the captions for Murray’s literary style and unearths key historical connections. When considered together, the collages and captions are one of the best examples of the black ekphrastic tradition, which would later also include the photographs of Carrie Mae Weems, Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust, and Kara Walker’s silhouettes.

Bearden’s Profile series has been gloriously returned to prominence through the exhibition “Something Over Something Else”; O’Meally’s Reader has done much to further our understanding of Bearden’s art, life and legacy in context. In particular, Bearden’s Artist with Painting & Model must be reckoned with as one of the most significant artistic productions of last century. It is, in Paul Devlin’s brilliant metaphor, “like the neck of the hourglass,” which compels the viewer “to return to the beginning and reconsider each piece” in the Profile series. Bearden’s art asks us to reconsider ourselves, too. For O’Meally, who has spent decades researching Bearden and his circle, meditating on the artist brings to mind one of the most poignant questions of life. “Who are we?” O’Meally asks. “For starters, Bearden’s pictures say, we are the collage people: individuals and communities with big hands and big hearts, scarred and battered but reassembled and layered. We are drawn together.”