In her recent New York Times Bestseller, Rebecca Traister writes, “On some level, if not intellectual then animal, there has always been an understanding of the power of women’s anger: that as an oppressed majority in the United States, women have long had within them the potential to rise up in fury, to take over a country in which they’ve never really been offered their fair or representative stake.” As Traister rightly points out, there exists a muted rage among many women, which eventually surfaces in social media posts, rallies, and other overtly political actions. Yet at the same time, silence proves to be an often-overlooked expression of women’s anger.

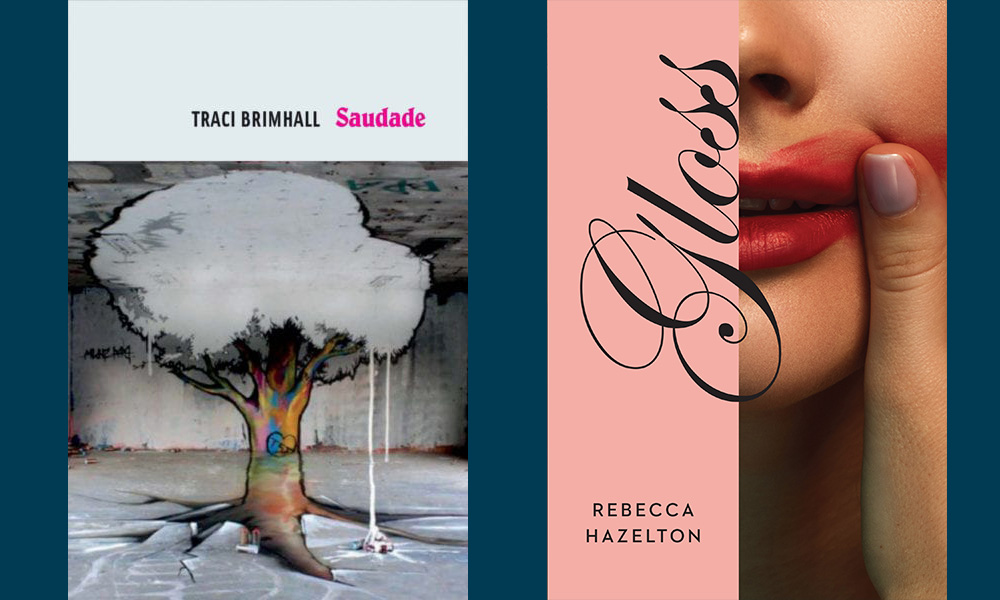

Recent poetry collections by Traci Brimhall and Rebecca Hazelton explore the ways silence, and a purposeful withholding of narrative context, can have revolutionary implications. More specifically, these gifted poets create a power dynamic between the artist and her audience, in which the text’s silences and elisions become a show of agency for the feminist practitioner. By choosing who has access to the imaginative world they’ve created, and withholding artistic intent, they ultimately assume a stance of empowerment as they inhabit the predominantly male artistic tradition they have inherited.

In many ways, this cultivation of mystery — arguably even difficulty — comes through most visibly in these poets’ relationship to traditional forms. We witness Brimhall and Hazelton inhabiting the familiar couplets, tercets, and quatrains of an inherited artistic tradition, yet creating a provocative reversal of power from within their well-trodden structures. As each book unfolds, the forms which we’ve come to know are made suddenly and wonderfully strange by a careful, intentional, and disruptive withholding of narrative context. As Brimhall herself observes, “O mystery. O hopeful stab of joy.”

¤

Rebecca Hazelton’s Gloss begins with a poem entitled “Group Sex,” in which the speaker explains, “There’s you and your lover and there’s also his idea / of who you are in this moment, and your idea of who / he should be, both of these like both of you but better—”. Even in these opening lines, Hazelton establishes a stance of power, which manifests first in her pairing of direct address with the poem’s undoubtedly intimate dramatic situation. By excising the narrative scaffolding that normally surrounds a love scene, and beginning in medias res, the poem challenges the reader’s likely sense of entitlement to exposition. The poem’s use of second person amplifies, and suits, the poem’s overt defiance of our belief that a story takes the form of a progression, a gradual and slowly paced dolling out of plot elements.

As the book unfolds, Hazelton invokes couplets, tercets, and the lyric while at the same time assuming power and agency as she decides how much, and how little, the reader is allowed into the imagined terrain she is constructing. She writes in “Love Poem,” which takes the shape of pristine tercets,

Sometimes you are the more elegant

of the two cigarettes in the cut-glass ashtray.

Sometimes you are the smoke curling upin the slow frame rate, cutting to mist

on a dark road rising.

Though offering the illusion of order, Hazelton begins once again in medias res. In doing so, she eschews language in which there exists a clear correlation between the signifier and what is signified. Instead, she chooses what philosopher Paul Ricouer once referred to as the “symbolic” dimension of language, that image or detail that generates meaning and possibility for the work’s audience. As the “cigarettes” and their “cut-glass ashtray” multiply in their potential readerly interpretations, Hazelton withholds the authorial guidance that has become all too commonplace in contemporary poetry. Within the confines of seemingly orderly tercets, Hazelton creates a provocative reversal.

Hazelton assures us, “You might be forgiven for thinking there’s an order to things.” Yet she skillfully challenges the power structures that we have become accustomed to in poetry, in which one caters to an outdated notion of the reader as arbiter, as consumer, rather than an actual constituent of the text. In many ways, this idea of the reader is steeped in a tradition that is less than hospitable to women’s voices. “When he is a woman I feel optimistic,” she explains. Hazelton’s artful revision of this gendered model of reading opens up the possibility of for new ways of interpreting, and relating to, feminist texts. As Hazelton herself asserts, “No cake baked by man from woman born / will small me now.”

¤

Saudade offers a narrative in fragments. Like Hazelton, Brimhall purposefully withholds the readerly luxury of exposition, those moments in which the work’s connections and confluences are made abundantly clear. Presented as a story told in many voices, it is the space between these character’s voices, narratives, and perspectives that becomes charged with possibility. For Brihmall, creating a polyphonic text proves to be an inherently feminist endeavor, as Saudade’s myriad silences and elisions challenge her audience’s expectations, and in doing so, cultural beliefs about what the task of reading should look like.

For many feminist practitioners, the act of interpretation exists as a patriarchal enterprise, in which the reader strives to attain mastery over a given work. “Perhaps I can control him,” Brimhall’s speaker conjectures. Indeed, she shows us that the polyphonic text, in its bright apertures and its provocative ruptures, resists a reader’s attempt to dominate and colonize the text through their interpretive efforts. In the text’s silences, there exists little hermeneutical certainty. “Why not a prophecy and it’s interpreter instead of angels chaperoning a resurrection?” Brimhall’s speaker asks. Here she may very well be reflecting on her own craft, as the book’s polyvocal structure cultivates greater freedom for both the poet and her reader.

As she brings together mythology, familial history, and divinatory poetics, Brimhall ultimately allows the space words to speak. She writes in “For the Glory,” “O heavenly dark rendered in a woman’s body. I wake / and find the grave empty. My wife says she is ready / to serve a god instead of a man.” What is most striking about these lines is the way that each sentence asks us to take a conceptual leap. Though offering us the semblance of order, these neatly constructed, grammatically faultless sentences contain chasms between them. Much like Hazelton’s unconventional use of couplets, tercets, and other familiar forms, Brimhall’s adherence to the rules of language ultimately expands what is possible within their strictures. As Brimhall herself commands the reader, “oh, resist.”

¤

If readerly interpretation exists as a wielding of mastery, how can feminist practitioners change these structures of power, claiming some of that agency for themselves? In their innovative feminist texts, Brimhall and Hazelton use silence, rupture, and elision to offer a provocative reversal, deciding for themselves who is allowed into the imaginative terrain they have created, and to what extent. Though typically envisioned as a form of oppression, an unwanted destruction of voice and agency, Hazelton and Brimhall reframe silence as a source of power, an intentional withholding and a necessary challenge to a kind of readerly entitlement. As Brimhall observes, “Here’s the never of silence, the yes of an idolizing crowd.”