In a recent piece in The Guardian, Nick Drnaso says he didn’t come to comics until he was an adult, and that his work is more influenced by TV and film than other cartoonists. Like a director shooting to the side of violence, like a horror movie holding back the monster, Drnaso finds tension along the periphery of the nightmare. His comics evoke dread with quiet and patient shots.

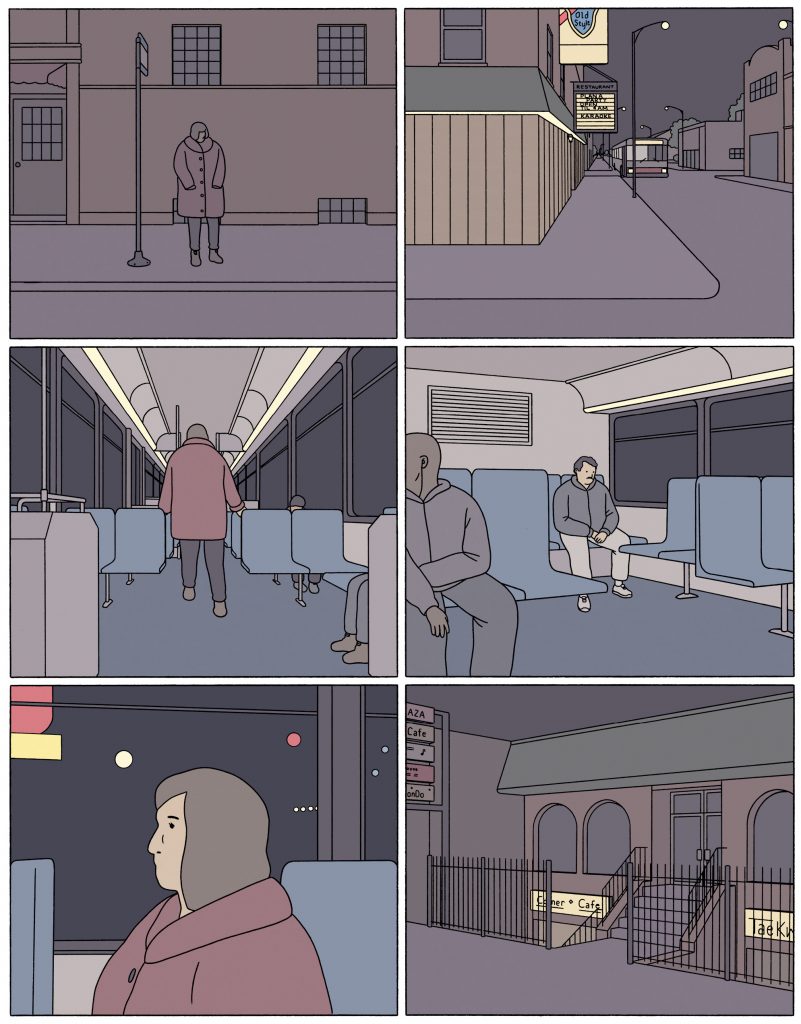

Drnaso’s new graphic novel Sabrina is indirectly about the titular character gone missing, but the story is actually built of the uncanny minutiae left in the wake of that violence. While most authors would skip long hours at the office, repetitive meals, and scrolling through the internet before bed, that is the stuff that Sabrina is built of. The most unsettling effect of this graphic novel is the pressure Drnaso finds between tedium and horror, in waiting for something to happen, in it maybe never happening. It’s hard to say whether the man on the bus is a threat. Maybe he’s just a man on a bus.

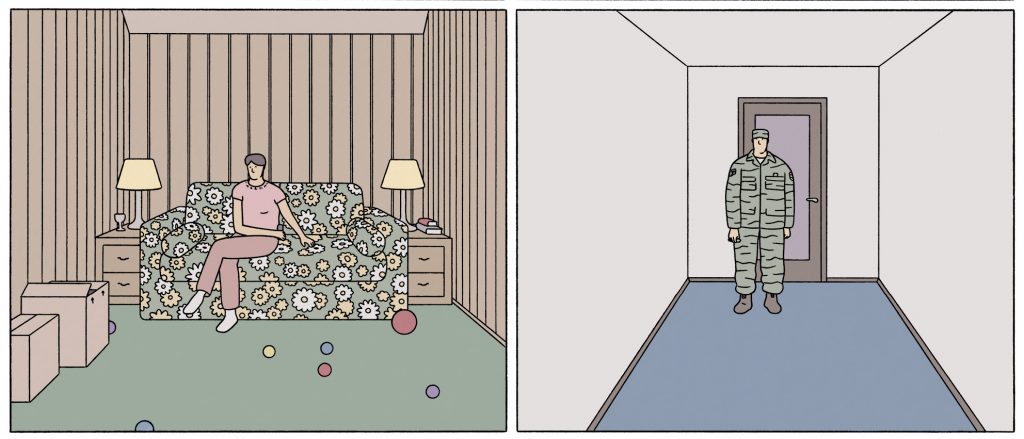

In the aftermath of Sabrina’s disappearance, her grieving but aloof boyfriend Teddy leaves Illinois to stay with his childhood friend Calvin at a Colorado Air Force base. Teddy is trying to recover from his loss: first, the one caused by Sabrina going missing, and then by Sabrina turning up in a viral video of her murder. Teddy makes slow progress toward reckoning with what happened. While there are endless opportunities throughout Sabrina for these two men to bond, they spend most of their time behind their closed bedroom doors.

Sabrina features a fair amount of dialogue — as well as rants from the TV, radio, and Internet — but the most haunting effect rests in the simple illustrations of the still characters in space. Much of the story takes place at a bland military site where the men in matching service uniforms work in white cubicles. They live in houses that all look the same and kill time with insipid conversation: “Hey do you have any news for me?” one Air Force officer asks another as they stare at their computer screens. The other guy says, “What are you in the mood for? Current affairs? Sad? Funny? Celebrity gossip?” The first guy wants funny. The other guy says, “I found this over the weekend.” and reads much of a news story about corporate product placement in pornography. “Blah blah,” he says eventually. “You get the idea.”

In Sabrina, alongside the terror of random violence is the fear that these days will more likely continue. A deft portion of Sabrina is about the monotony of people whose jobs and lives are so specialized and insular that they cease to feel connected to anything related to the actual world. Then, senseless tragedy sends them even deeper within themselves. Instead of finding conversation in each other, they find it in the paranoid corners of the internet, or with TV and radio raconteurs. “If you’re willing to believe the official story, that an archetypal loner with no resources abducted and slaughtered a total stranger in his small apartment for no reason,” a radio host says in one scene, “by all means, pull that wool cap a little bit tighter.” Teddy sits on a bare mattress in his underpants listening. “There is something more complicated at work,” the radioman says. “You can be sure of that.”

Like the crime podcasts Serial or S-town, like the TV shows The Jinx or Making a Murderer, like In Cold Blood, Sabrina is a crime mystery that pulls the audience through the story by the gut. Led by an insatiable urge to know what happened, we also find out the many smaller tragedies of life along the way. Sabrina thrives at tracing American fear and paranoia by capturing the lonely people who get swept up in it.

Sabrina is Drnaso’s second book. His 2016 comic collection Beverly is also built of thrillingly eerie experiences. In many ways, Drnaso captures familiar moments of domestic American life. In other ways, those scenes have their skin peeled back. In Drnaso’s story “The Lil King,” for example, we encounter a young boy on a beach vacation with his parents and sister. In the car, and at the motel and beach, the little boy keeps seeing surreal images of butchered bodies. The suspense comes from wondering when, if ever, the rest of the family will realize that this family member is a psychopath.

Drnaso’s style of sequencing alternates between fast and glacial-paced, but in each frame, you know exactly where you’re landing. His storytelling is modest and he has an uncanny sense of how to shift a moment so it no longer resembles what it just did. At the end of Sabrina, when it seems the story has settled, there are suddenly loud and frightening bangs at Calvin’s motel room door. But it turns out it’s just the wrong room. “Get out of the hallway,” the man’s wife shouts at him. “You’re drunk.” They are both strangers to us. We linger with the man in the hallway, and then that’s it.