“I am writing as an ugly one for the ugly ones: the old hags, the dykes, the frigid, the unfucked, the unfuckable, the neurotics, the psychos, for all those girls who don’t get a look in the universal market of the consumable chick.” Virginie Despentes’s opening lines, like this one from her essay collection King Kong Theory, grab the reader by the throat. King Kong Theory was published in France in 2006 and brought to English by translator Stéphanie Benson in 2009. It earned Despentes a feminist cult following. Her books feature stylized focus on intense scenarios that approach the trouble of misogyny with a sharp blend of nonchalance and biting perceptiveness. She’s a feminist punk who follows in the tradition of writers like Kathy Acker. She’s transgressive, incisive, and her star is rising. In a recent piece for the Paris Review, Lauren Elkin writes about how Despentes has become very popular again in France due to Vernon Subutex, a trio of thick 19th-century-style novels, the first of which will be out in the US in fall 2019. Elkin writes, “In the past few years, everyone here in Paris has been reading Despentes again.”

Despentes’s sentences are short, fast, and stuffed with rich particulars. She builds luxurious scenarios and then smoothly pivots, and she does so very quickly. Her novel Apocalypse Baby, a scrappy noir set on the streets of Paris and Barcelona, opens: “Not so long ago, I was still thirty. Anything could happen. You just had to make the right choice at the right moment. I often changed jobs, my short-term contracts weren’t renewed, I had no time to get bored. I didn’t complain about my standard of living. I rarely lived alone. The seasons followed one after the other like a packet of sweet: easy to swallow and differently colored. I don’t know quite when it was that life stopped smiling on me.”

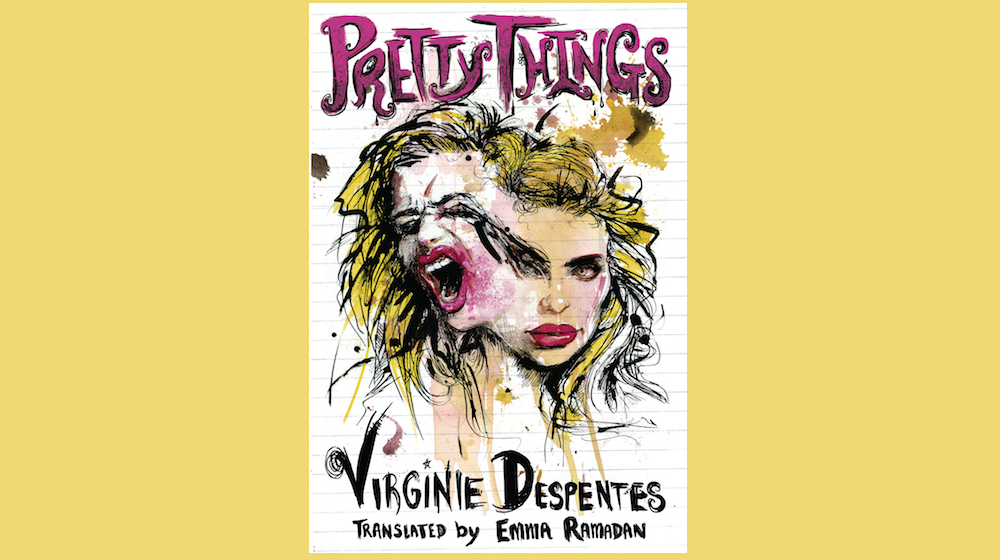

Translator Emma Ramadan and publisher Feminist Press now bring Despentes’s novel Pretty Things — a story of the dark demands of modern femininity — to English for the first time. Pretty Things provides yet another example of how effortlessly cool and ferociously smart Despentes’s writing is. As she demonstrates in the opening lines:

Chateau-Rouge. A terrace, on a sidewalk, in the middle of construction. They’re seated side by side. Claudine is blond, in a short pink dress that seems sensible but leaves some of her chest visible, the perfect doll, meticulously put together. Even her way of slouching, elbows on the table, legs spread out, has something refined about it. Nicolas’s eyes are very blue, he always looks like he’s laughing, about to do something mischievous.

He says, “Fuck it’s nice out.”

Claudine says, “Yeah, it hurts your eyes.”

The immediacy and immersiveness of Despentes’s openings echo throughout her writing. She sets up vivid scenes in an instant by making them pulse with sensory experience. She makes her characters and stories transform because she respects and realizes each absurd extreme, while also conveying how human it is to pivot. Pretty Things begins with Claudine, a woman who comes barreling into Paris for a grab at pop stardom. Determined and fearless, she arrives with a bag of her things and no place to go. A man creeps up on her in a McDonald’s at night, and she immediately makes him her victim. “She already knew that if she liked [his] apartment, she would stay as long as she wanted,” Despentes writes. “She knew guys like him: male nymphos with a compulsive and insatiable need to be reassured, so vulnerable. She possessed everything necessary to control that kind of guy.”

Claudine quickly involves her twin sister Pauline into helping her ascent. Claudine is sexy, but she can’t sing. Pauline, however, has a voice that she knows how to unleash. The idea is: Pauline will do the vocals. Once the songs are recorded, Claudine will take over for the music videos, the interviews, the photos, and eventually, the movies. But after they record a few songs, Claudine jumps out a window and kills herself; Pauline takes over the transformation, taking a much longer jump toward the beauty ideals once carried out by her sister. But Pauline turns out to be just as bullheaded and ruthless. “That cunt thought she was trapping me,” Pauline says to herself, “she’s actually done me a huge favor.”

Throughout Pretty Things, Despentes tackles topics around sexuality, gender, and power with laid-back aggression, and she renders the visceral experience of being a body tangled up in the sexual perversions of mainstream culture. In one scene, Pauline leaves the apartment in high heels. Despentes writes, “The boulevard she has to take is on a slant. In normal shoes she wouldn’t have noticed, it only sloped downhill a tiny bit. In high heels, the difference in level is insane, a truly perilous exercise.” She anxiously watches the obstacles, feeling each variation on the ground beneath her — through her feet and ankles, through her tilting and balancing body. She tries to ignore the whistles and advances from men on the street. Bodily tension vibrates through the prose.

Despentes’s writing is propulsive, exact, and luscious, all qualities channeled by her exquisitely talented translators: in addition to Ramadan and Benson, also Frank Wynne and Siân Reynolds.

Pretty Things is a fast-paced meditation on the precarity and disposability of the sexualized feminine body. Despite the projections of their father or their boyfriends or the many manipulative men they meet along the way, Claudine and Pauline still get a form of revenge through their modest obstruction of the star-making machine. To their strange credit, they care more about themselves than being famous. “Listen,” Pauline reminds Nicolas in one scene. “I’m all about the advance. As soon as I heard the word, I knew that it was my thing: advance.” Claudine and Pauline learn the trappings of contemporary sexual desire so deeply that they have a shot at performing for and triumphing over the perversion itself. Through Despentes’s propulsive, exact, and luscious writing, Pauline depravedly transforms but always with her own escape in mind. “Two hundred thousand in your face, cunt,” Pauline says to herself after her first single sells big. “At least that’s a language they all understand.”