Federico García Lorca may be standing over her shoulder, but he is not the only creative force on which Lois P. Jones draws in her new prize-winning collection, Night Ladder. Other influences include Picasso, Borges, Rumi, Sappho, Rilke, and Leonardo da Vinci, as well as other historical figures from Moses to Anne Frank. These figures contribute epigraphs to the poems, or appear through ekphrasis, making up the ladder of the book’s title. But Jones’s voice is singular, engaging both the intellect and passion while appealing strongly to the ear, to the sense of music related to duende, which Lorca defines in part as “a momentary burst of inspiration, the blush of all that is truly alive […]. It manifests itself among musicians and poets of the spoken word […] for it needs the trembling of the moment and then a long silence.”

In Jones’s poems, we experience both the trembling and the silence. She brings us sounds — “bells / […] crying all around, no bones to cradle them,” “strange razor calls/ of rooftop birds, our vowels rain-lipped” — as well as images laden with the pleasure of sound, like “woodbine and winterberry,” “part lather, part lavender,” and “needles/ of hoarfrost […] shins/in nettle.” She nurtures the way consonants and vowels intertangle, stimulating all the senses. In “The Scent of Ariel,” a seemingly humble scene overwhelms the reader with its richness of texture and sound:

Ariana […] brings extra towels

that smell sweet as a tamale husk, rough as a night

of too many sangrias when bells

of the Parroquia jangle like cast iron pans

Throughout the collection Jones creates an internal structure based on subtle references to Lorca, the great Andalusian poet. We are introduced early on to his voice in an epigraph to “Unmarked Grave”: “All I want is a single hand. A wounded hand if that is possible.” Jones extends that hand, generously, in a gesture of aesthetic union:

Beautiful man, with your brows of broken ashes

and eyes that migrate in winter,

a hollow in your hand

where the moon fell through.

Her generosity is a response to what Lorca has given us, at such great cost, through literature:

I could have kissed your mouth,

passed an olive with my tongue,

the aftertaste of canaries on our breath.

Through Jones’s masterful images, we experience Lorca’s flirtation with death and his assassination. Above all, we marvel at his intrigue with language, which can bridle the human condition and send it racing into new terrain. In Jones’s poems, as in Lorca’s, duende and qi come together on the page in an act of passion, an explosion of energy, ensuring that the words live on in the mind long after the reader has closed the book.

In her ekphrastic poems Jones blends her verbal imagination with that of visual artists, underscoring the resonance between the two genres. In “Ways to Paint a Woman,” a response to a painting by Ali-Al Ameri of the poet herself, she writes:

Sometimes you must paint it yellow —

listen with the eyes: honeycomb and maize,

golden rainflowers.

Transform with your softest brush,

the way Lorca’s bathing girl liquefies

into water […]

And she continues:

Paint as you would before you awaken,

when sunlight falls like milkweed

and you are an empty silo

There is an openness, a fearlessness in her approach. Jones ends her response to Susan Dobay’s painting Awakening with these lines:

You were never

really a virgin.

Every part of you

meant to be known

born to say yes.

Each poem underscores a sense of intimacy with the world, as in “Under a Mendoza Trellis”:

Everything flows through me, but nothing

is lost, not a drop of wine or a breath

of rosemary.

[…] look straight into

my blood and I am as full as the grapes

in the canopy.

Jones’s responses to literary and visual artists are weighted with wisdom. They have taught her to attend to the world, to see what others might miss, to look for new perspectives. For example, in the poem, “What the Chestnut Tree Saw,” Jones sketches a reflection of Anne Frank mirrored in the eye of the chestnut tree she admired before her capture:

A sun rises. A car halts and spills

its black-clotted men. The last scampering

as you grab your twill coat, look up at me,

then away.

Night Ladder is an offering to mind and body. The ladder’s ascent is as much horizontal as it is vertical. Qi flows through its white spaces, creating an energy field comparable to the waters rushing down the San Gabriel Mountains in the melodic “Big Tujunga.” While reading this collection, be prepared to “let your mind tango with creosote/ and mesquite,” to sense “[s]ome spirit/ rushing past you like tumbleweed,” and to realize that “[t]ime makes you thirsty,/ hungry for what really feeds you.” These poems open us up, one part at a time, until we face new vistas — unexplored realms of the human spirit.

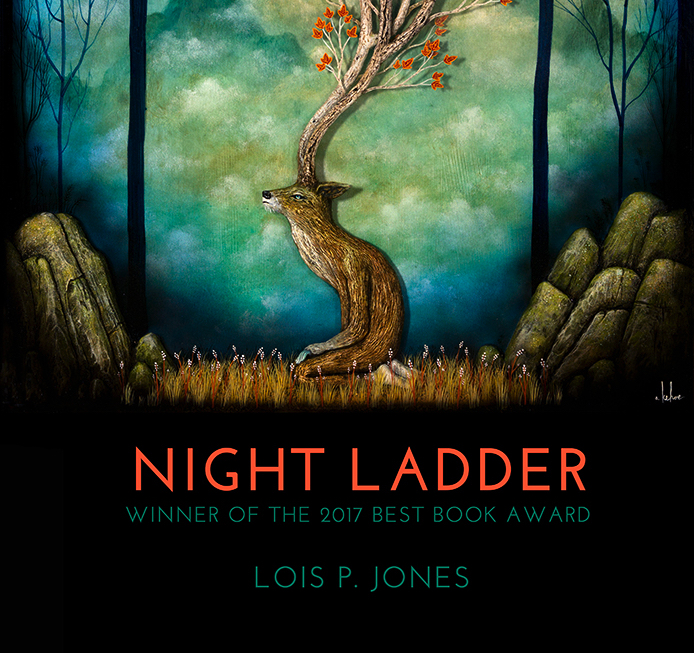

Night Ladder, by Lois P. Jones. Winner of the 2017 Best Book Award, Glass Lyre Press, 2017.