The October Gallery, London, 1988: Kathy Acker and William S. Burroughs sit across from each other in matching wicker armchairs. Acker feels almost painfully young, sporting a college student’s shaved, bleached head and a cheap-looking velvet shirt. Burroughs is old — his hands shake as the pair discuss his work, his life, and his new paintings on view at the gallery. Towards the interview’s close, the pair reaches an impasse:

“To what extent is it possible to save ourselves?” Acker asks.

Burroughs balks. “Impossible question to answer. What do you mean by us? And what do you mean by ourselves?”

“Is that an answer?”

“I feel very little empathy with other people,” says Burroughs. “When you speak of a ‘we’ it would be a pretty small ‘we.’ Most ‘we’s you can excuse me out of.”

Acker is silent. The gravity of his rejection is palpable: Acker wants his “we” like a dog and a bone. Her writing is littered with references to Burroughs — most notably in her rampant and controversial use of literary appropriation, a technique that almost got her sued by Harold Robbins for her use of his writing in an early work. Through the haze of 1988 videography, the two writers could not seem further apart: Burroughs is blissfully ignorant of the younger writer’s adulation of his work, easily shrugging off her attempts for connection. In death, they are unexpected bedfellows: nine years after Acker’s London interview, in August, Burroughs died. Three months later, so did Acker. The last lines of her New York Times obituary are in praise of him. Her desire for community among the avant-garde was insatiable during her life and unsatisfied until after her death, when a slew of releases and re-releases gazed anew at the writer’s legacy. Chris Kraus’s After Kathy Acker, Olivia Laing’s Crudo, and I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995-1996, Semiotext(e)’s compendium of emails between Acker and McKenzie Wark, are, respectively, biographical, fictional, and epistolary recapitulations of Acker’s legacy. Acker’s inclusion in Melville House’s The Last Interview series, where her only female companions are Jane Jacobs, Nora Ephron, and Hannah Arendt, marks her entrance into a broader group of notable feminist artists — a far cry from the niche world that proffered Acker during her lifetime. These new examinations of the author catapult Acker into the mythic canon of admired, dead women.

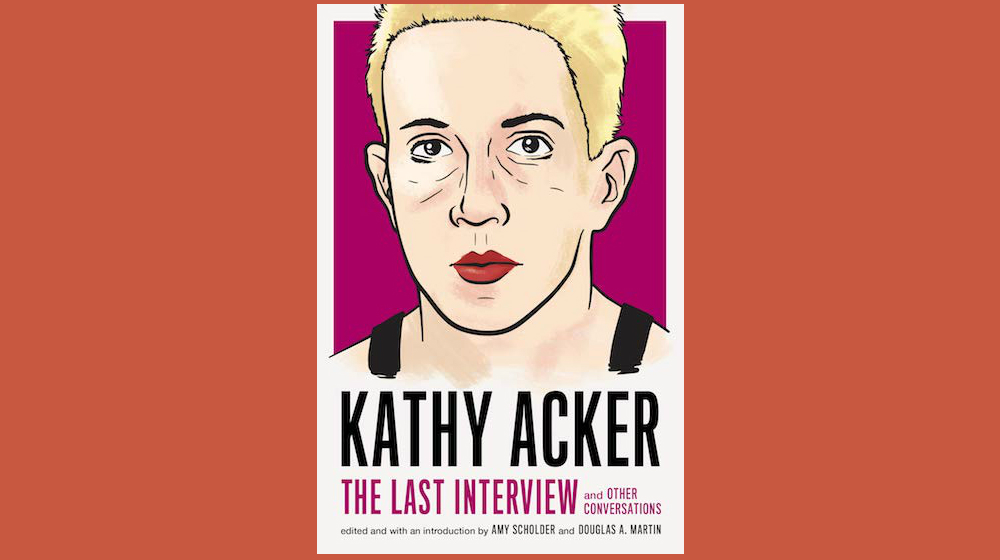

Kathy Acker: The Last Interview, from Melville House, is the newest attempt to reconsider Acker’s career after her death. Acker’s contemporary attention has welcomed a new crop of readers to her prolific oeuvre — I am one result, given Blood and Guts in High School by a friend in actual high school, where Acker’s vulgarity and rhythm opened me to a locus of divergent femininity previously obscured by the pop girl-dom(s) of the 2000s. The collection traverses the terrain of the latter section of Acker’s career, after the writer’s rise to underground lit fame with the release of Don Quixote and Great Expectations. The swath of interviews arranged by the book’s editors, Amy Scholder and Douglas A. Martin, is entertaining, poignant, and often troubling, conjuring a surprisingly intimate portrait of the artist that revels in her contradictions. Consistent throughout the collection is Acker’s own personal relationship with her interviewers, including her close friendship with Scholder. Friends, lovers, and Acker(s) fill the pages of The Last Interview, resisting the traditional biographer’s narrative inklings in favor of a glorious polyphony. Here, Acker’s interviews echo her life as they stumble and shout her memory, pausing for moments of pain, pleasure, and humor along the way.

Questions of honesty and authenticity trail Acker’s memory, where the presence of conflicting accounts of and by the writer raise biographical difficulties at the heart of the genre. In an unexpurgated interview between Acker and former lover and Semiotext(e) heavyweight Sylvère Lotringer, the pair discuss readers’ inclination to attribute autobiography to Acker’s first-person narrative fiction. Acker remarks, “I was experimenting about identity in terms of language … I just wanted to figure out how the word ‘I’ worked.” The first person, they agree, provokes an illusion of truth for the reader — an assumption that fascinated Acker throughout her lifetime. As the main character Janey says in Blood and Guts in High School, “You, the thing you called ‘you,’ was a ball turning and turning in the blackness [ … ] every time the ball turns over you feel all your characteristics, your identities, slip around so you go crazy.” Acker’s relationship to the “I” in her writing, characterized by inconsistency and experimental “slips” of the self, carried over to her own accounts of her life. In After Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus writes, “Acker lied all the time. She was rich, she was poor … she lied when it was clearly beneficial to her, and she lied even when it was not.” Acker’s changing narrative of her own life story slaps away the grubby hands of the biographer as they snatch, foolishly, at truth. What Kraus emphatically, almost reverentially calls “lies” become, under Acker’s watchful eye, a more fundamental questioning of the stability of identity. The plethora of voices — be they Acker’s personae or her conversational partners — present in The Last Interview offers one interesting injunction into the problem of biography and Kathy Acker, letting the author “[turn] in the blackness” without the interrogation of honesty.

The Last Interview uses Acker’s death as its premise, a conclusion that the chronological collection appears to wander toward almost unwittingly, unchained from the burden of probing narrative investigation. What emerges is what Martin calls “culled highlights,” an attempt to conjure “key moments in her dynamic formulations, the foundations she was always shifting.”

There’s a joy reserved for this kind of obituary spirit — the pleasure of knowing someone, like Acker, who resists summation. Scholder and Martin’s decision to focus primarily on the last decade of Acker’s life brings the writer’s unique relationship to pain, sex, and the body to the glistening fore, suggesting Acker’s death and often eschewing it in the same breath. Moments of tragedy are matched by a guileless humor: in a 1991 interview with Andrea Juno, Acker remarks, “I once had a little cyst in my breast taken out, and I said, ‘Never again! Even if I get cysts in my breasts — I don’t care!’” While Acker may have resisted Scholder and Martin’s decision to order her interviews in such a neatly linear fashion, the premise of the book — a dead author — guides the collection without dominating it, ceding to Acker’s articulations of weightlifting or language, cancer or pop culture.

Acker’s relationship with other people forms the bedrock of the collection, supplanting the stern voice of the posthumous biography with the familiar, informal words exchanged by the author and those who were (are) close to her. In her introduction, Scholder writes, “I realized that what I wanted to remember about Kathy was the conversation … what I like about the interviews is that Kathy isn’t alone.” Indeed, even the interviews feel less like magazine profiles than they do pillow talk. Acker consistently collapses the harsh distance between herself and the interviewer: in one response to Dean Kuipers’s question about taboo in her writing, Acker responds, “Well, you’ve read the book.” Her dismissal of interview conventions reveals the usual invisibility of the structure itself, instead focusing on the intimate connection between two people talking. In Acker’s interview with The Spice Girls — a truly wonderful collision if there ever was one — her persistent first person narration fuels the conversation. She writes, “I like these girls. I like being with them.” The world created by the pop collective fascinates Acker, especially in their relationship to female-fronted community. “Look,” Acker says, “I’m feeling stranger and stranger about these politics based on individualism.” The girls agree. Ginger Spice mentions Freud. I cackle from my chair: Acker believes in girls — so much so that she seems to create them, worlds of them, wherever she goes. In an interview for Artforum, she comments, “My strongest desire … is to make it possible for people like me to be in society.” Acker’s community may be her most consistent truth, revealing a starkly authentic belief in sparking conversation and kinship between women.

The Last Interview confirms Acker’s world of friends, lovers, and collaborators as her afterlife itself, graciously allowing the reader to witness the deep importance of the like-minded in the writer’s life. This may be Acker’s most enduring gift — literary insurrections aside. I am moved now to remember what Kathy Acker has meant to me, how her articulations of blood and sex, pain and strength, gave me a womanhood away from the anemic perma-adolescence favored by the mainstream. Acker’s recent posthumous titles contain an irony only deep, heart-bound friends may understand: that in real community there is no last interview, nor is there really an after. This world, the one full with Acker’s spirit and drive for kinship, is not one that will easily leave the present tense. In death, Scholder and Martin honor the avant-garde female artist by loving her. Acker’s “we” is endless and persuasive — at the end of Burroughs’s life, the pair met at his home in Kansas. His openness and kindness surprised Acker. It doesn’t surprise me: “we” were and are lucky to know her. The noble commitment of Acker’s friends to her enduring memory in The Last Interview is a triumph, breathing new love into her afterlife.