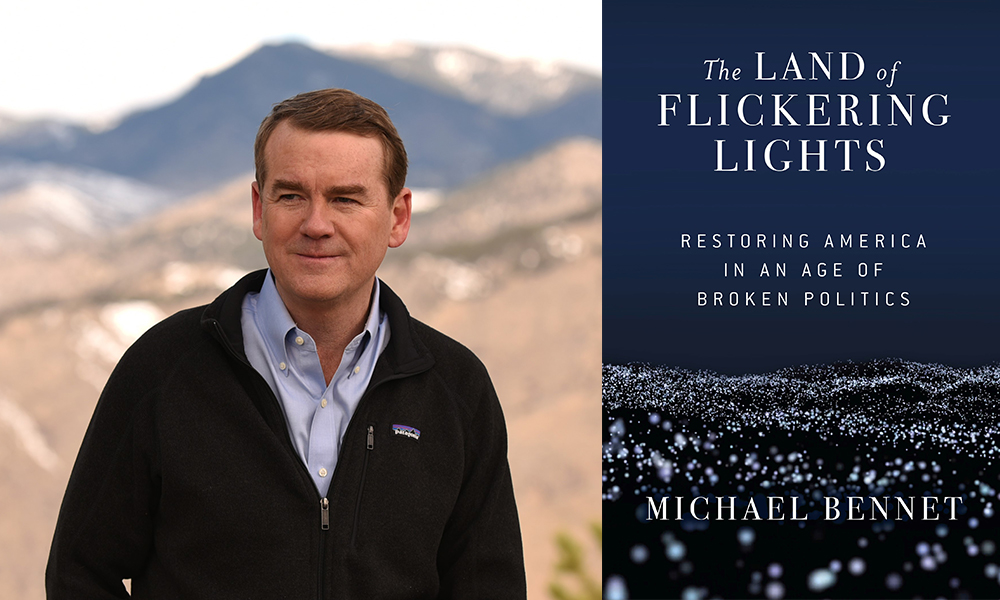

Why should we all consider ourselves “founders of this American republic”? Why can’t our democracy thrive unless we do so? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Senator Michael Bennet. This present conversation focuses on Bennet’s book The Land of Flickering Lights: Restoring America in An Age of Broken Politics. Bennet has represented Colorado in the US Senate since 2009. Recognized as a pragmatic and independent thinker, he has built a reputation for taking on some of our greatest national challenges — on topics ranging from education, to climate change, to immigration, to healthcare, to national security. Prior to the Senate, Bennet served as Superintendent of the Denver Public Schools. He lives in Denver with his wife and three daughters.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start, in Abraham Lincoln’s terms, with the need to disenthrall ourselves of politics’ seductive and/or repulsive fascinations? Could you give a couple examples of what it might look like at present for us to relearn that our politics only pick up value by facilitating constructive self-governance?

MICHAEL BENNET: I actually have that quote right here, taped to the wall beside my desk. Lincoln says: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.” And for today I’d add that, even before Donald Trump arrived, our own occasion was piled high with difficulty. Even before COVID, we faced an occasion piled high with difficulty. To be honest, during my almost 10 years in the Senate, I’ve seen a consistent inability of the federal government to respond in meaningful ways to that level of difficulty, largely because we cannot disenthrall ourselves from political gamesmanship (let alone the prevailing dogmas).

By far the most problematic abuses of basic mechanisms of government have come from a tyrannical minority of Freedom Caucus members. They brought to Washington, DC a cartoon version of what the founding fathers had accomplished, and they’ve sought to disrupt our exercise of constructive self-governance ever since. So if you turn on cable television, you’ll see self-appointed spokespeople for competing ideologies clashing. You won’t hear much about which policy measures might best help to improve prospects for the next generation of Americans. Outside of COVID discussions, for example, when did you last hear someone on a cable-news panel give concrete policy suggestions for improving our public education system? But high-quality education is one of the most important public goods we have. And if we could orient our focus towards the next generation’s needs, then we could start disenthralling ourselves from ideology and from political spectacles — and could make a lot more progress on outcomes we all claim to want.

Well The Land of Flickering Lights’ most redemptive refrains occur in your accounts of live, face-to-face (at least pre-COVID) town-hall discussions. What have you witnessed happen at an exemplary town hall, as the strengths of our diversity and the wisdom of honest debate take hold?

At the book’s end, when I give suggested readings, that comes out of my fondest moments from town halls. It doesn’t happen every time, but occasionally somebody walks up after a town hall and asks: “What are you reading? Because whatever you’re reading sounds pretty different from what I’m reading.” I do think that kind of open give-and-take is redemptive, for both of us. We all need more opportunities to get beyond the rigid partisan disputes, and move forward into more independent lines of thought, and surprise ourselves by who we can relate to and who we can work with.

During the Affordable Care Act’s rollout, for example, the instructions from Washington for Democrats were: “Don’t do town halls” [Laughter]. But I hosted one town hall after another. I wanted to go to Coloradans in the state’s reddest parts, say on the eastern plains. I can remember showing up at Lamar Community College, and saying: “Well, I’ve put together a deck of slides on our healthcare system. Do you want me to show the deck?” This was at the height of the Tea Party’s initial very powerful wave, with very strong town-hall participation. This guy in the middle of the room said something like: “We don’t want to see your deck. We don’t care what you brought.” And then as often happens, an older woman sitting on the side of this auditorium in Lamar said: “If he went to the trouble of putting together these slides for us, then we should at least let him show them.” And I walked up to this gentleman in the middle of the hall, and put my hand on his shoulder, and said: “Listen, I’ll start with the slides. If at any moment you decide you’ve seen enough, then I’ll stop.” And we all ended up having a very rich conversation about the state of US healthcare — which, by the way, hasn’t been very supportive of people on Colorado’s eastern plains.

Much of the audience might not have left this town hall saying: “Oh my god, Obamacare’s the greatest healthcare policy in the world.” But I do think we got to a shared understanding of the nature of this problem we needed to solve. And we all could acknowledge the particular difficulties this problem posed for people in the room that day. So then we could move on to the question of: “Well, what should we now do about that?” If we can reach the point of identifying everybody’s mutual interests in solving an issue, then even if we come at it from completely different perspectives, we can get somewhere together.

A big piece of my book focuses on the fact that we shouldn’t just expect to agree with each other, and get mad or give up when that doesn’t happen. Actually, out of those disagreements, out of that give-and-take, our democratic republic, in theory (and also I believe in practice), fashions much more imaginative and durable solutions than tyrants acting on their own ever could. The best forum for doing this, in my view, remains the town hall. Ideally, I don’t even give a speech at the beginning. I simply say: “Any questions, any criticisms, whatever anybody wants to talk about — that’s what I’m here to talk about.” I wish more than almost anything that we could figure out some equivalently effective social-media forum. Of course so far that’s ludicrous.

Now for slightly more abstract conversations, first what does it mean to you personally to reflect on the founders “who constructed the ideas upon which our republic was built and which enable it to endure, thrive, and grow”? And why should we think of these founders as also including “all of those who, down the years, have expanded America’s promise” — hopefully extending all the way to ourselves?

I’ve been thinking about that a lot since writing this book, in part because of what we’ve seen in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis. I’ve always sensed two competing strains of beliefs and basic impulses coursing through our history, from the founding onwards. One set of beliefs offers the highest ideals ever expressed in writing, the ideals in our founding documents, particularly the Constitution but also the Declaration of Independence. But we’ve also been dogged since the very beginning by our worst impulses, which at first took the form of certain Americans (including many founders, of course) enslaving their fellow human beings.

Our history has forever gone back and forth: moving toward progress, toward greater democracy, toward true freedom and fairness — but also with that progress always potentially provoking a backlash. One of the most striking examples comes with the so-called Redeemers responding to post-Civil War Reconstruction. Or in our own time, I would argue that the Tea Party’s rise came in response to Barack Obama’s election. And now, in response to this unprecedented reactionary (and incompetent) Trump administration, I think we’ll also see a constructive pushback against that. I sense further shifts in this conversation we’ve been having since the very beginning, and that will probably continue between Americans until the very end.

So within that broader context, I think about the original founders as a group of living politicians, not as deities or infallible beings. I recently read Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom book tracing how, with the founding of the Virginia colony more than 400 years ago, we already see these two foundational forces of American freedom and American slavery arising in exactly the same place at exactly the same time. Morgan offers this fascinating economic history, directed at answering some of those questions we can’t help asking, such as: “How could Thomas Jefferson have written these magnificent words, while enslaving his fellow human beings? How could George Washington have supported this philosophy and fought for American freedom, and at the same time enslaved human beings?”

For all of those reasons, in my own book I argue that we need to think of our founders much more expansively than just the people who wrote our foundational documents. The founders writing those documents didn’t consider my daughters worthy of the right to vote, for example. We’ve needed additional founders, and a much more diverse range of Americans, to fulfill the highest ideals that our constitutional framers put on the page. We need to think of these later Americans, breathing life into abstract ideals, as just as much our founders. And then further, like you said, we need to see ourselves, and each other, as founders. We need to ask ourselves and to ask each other: “How to make sure that we all can and all do live up to this sacred responsibility?”

Because you can be a founder but not actually fulfill your commitment to our republic. You could end up as a founder who ultimately fails the republic. Or instead you could take as a model a founder like Frederick Douglass, or like John Lewis. I can’t think of a better contemporary example than John Lewis of an American founder who, from such an early age until the day he died, understood and embraced his responsibility to the republic. Only when we all acknowledge and understand that elevated sense of our own responsibility, only when we all live our lives as founders of this American republic, can our democracy thrive.

In terms of democratic thriving, questions of scale also come up throughout this book. In local contexts, you often detect Americans’ pragmatic knack for fashioning those imaginative and durable solutions you’ve mentioned. In national politics, you often see blowhards and bad-faith actors dominating the discussion. What prospects exist for scaling up those localized capacities — or when could decentralizing certain national projects make sense, say by distributing our federal bureaucracy more widely across the US?

First on the national level, we absolutely need to take on a web of special interests, a whole special-interest infrastructure that has metastasized around Washington. Of course some version of this web exists in other places as well. It exists in state capitals, in Denver and others — but not remotely to the same degree. Our nation’s capital today has a strange insulating effect on people elected to come here. You don’t see the same kinds of behavior from people elected to city council or to most state legislatures. The permanence of this Washington-based infrastructure has a categorically different impact on legislative operations.

When we debate the Affordable Care Act on the Senate floor, for example, that doesn’t just mean debating the merits of the bill before us. That means factoring into the account 50 years of gives-and-takes, 50 years of disputes and occasional cooperation, 50 years of special interests lobbying intensively on one side or the other. These organizations know they’ll outlast any elected official. They know their members won’t waiver in conviction and commitment and support. But that all can get in the way of our political system’s proper functioning — particularly given the emphasis that our constitutional structure puts on compromise.

So first of all, we need to diminish the importance of money in our political system. I’ve proposed both big ideas and small ideas on that topic. As one big idea, we need to overturn Citizens United. As one smaller but important idea, we need to tell everybody in Congress: “You know what? Maybe you shouldn’t raise money from lobbyists while you’re in session.” We need a whole program of progressive reforms, of the kind Teddy Roosevelt and others in his generation not just proposed but implemented.

To make that kind of broader reform possible, we also need to make sure our citizens can vote much more easily. We need to empower the franchise. We all should want many more Americans not just having theoretical access to the ballot, but actually voting. We need American voters holding national officeholders to account with the same strict standards by which we hold local elected officeholders to account. That doesn’t just take new legislation. That doesn’t just take new regulation. That requires a combined institutional and broader cultural shift.

If any school-board member or superintendent decided to just shut down the school district to make a political point, with no real concern about what the kids themselves need, Americans would rightly send that person packing. The same goes for our city councils, where constituents just lack the patience for these stunts. But then what happens ritually here in Washington, almost every year? We shouldn’t have the ability to shut down our federal government just to score political points either. Legislators and executives who operate that way should lose their job, just like you’d lose your job as a city councilperson. So that requires voters to say: “We won’t put up with this kind of bad behavior anymore.” And in the end that only happens when more Americans can take up the franchise and exercise citizen accountability.

So now pivoting to The Land of Flickering Lights’ five lived episodes of recent federal-government dysfunction, your first episode starts with both parties tearing down written and unwritten Senate rules, particularly around judicial appointments. And what makes this account so moving comes from you not simply needing to decide whether you’ll follow the Constitution, whether you’ll play the role of petty partisan or of magnanimous American. Instead, you sense Republican Senators foreclosing possibilities for proper government functioning, and you have to figure out how to recalibrate that functioning, and which ends justify which means. So we know your retrospective regret on some of these procedural votes, but what did that whole complex calculus feel like in real time?

Yeah, I hadn’t much thought about it that way, but being there in the moment, when we’d already had a couple decades of bad behavior from both sides on judicial nominations, really did feel like this dangerous possibility for pushing ourselves past the point of no return. Certain people (with Mitch McConnell the lead example) were so openly acting in such bad faith. So that does shift the calculus on what it will take to preserve our basic democratic institutions. In that situation, you really can feel the ground shifting below your feet.

For one specific example of how this all played out, I made the argument that, both on the merits and as a strategic matter, Democrats should not filibuster the Neil Gorsuch nomination, even after Republicans had denied so much as a hearing for President Obama’s widely admired nominee, Merrick Garland. I didn’t want the Republicans taking up the nuclear option on a Supreme Court nominee, taking away our ability to filibuster — particularly given that the next nominee after Gorsuch might have a strong sway on the Court’s balance of power. I lost that argument with Democrats. McConnell pulled the trigger and used the nuclear option. And at that point in our new post-nuclear and increasingly partisan world, I just didn’t feel any responsibility to vote for this qualified nominee. So I guess what happened in the Senate had changed me in that way.

But then writing this book, it helped to go back to Thucydides, to his account of a civil war consuming the ancient city of Corcyra. Thucydides describes this situation thousands of years ago when “the party caprice of the moment” provided the only standard. He worries about this collective dysfunction becoming a permanent state of things. I’d wanted to make that argument all along: that before we descend to this permanent state of things, before we reach a no-holds-barred confrontation, before the standard of conduct becomes whatever you can get away with, we need to put the guardrails back on. No city can thrive, no business or religious institution or civic institution (or certainly no legislative body) can thrive when the standard for engagement becomes: “Let’s see what our side can get away with.” We’ve basically reached that point now, in terms of the Senate’s confirmation process for federal judges.

Yikes.

I mean, look at Mitch McConnell gleefully saying that if we lose Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then he’ll bring forward a nominee in these final months of Donald Trump’s presidential term. I could see this current Senate, on the last day of Trump’s presidency, in a lame-duck legislature (and with a new president already voted in), confirming another Trump Supreme Court appointment — and all after McConnell made the completely fatuous argument that we should “let the people decide” on the Merrick Garland nomination. So you’re right: once these institutional dysfunctions start happening, it’s very hard to find your way back to a more constructive process.

In the case of judicial nominations, it’s hard to believe that this current system works better than the process that existed during my own time in law school. Back then, a qualified judge would almost inevitably receive a vast bipartisan majority of Senators’ confirmation votes. Every time the Senate maintained this norm, that reasserted the independence of our national judiciary. That wasn’t just a case of less temporary partisan insanity. That was an active reinforcement of our shared and foundational constitutional principles.

I almost can’t imagine my own generation of politicians reconstructing that kind of positive and essential reinforcement of basic democratic functioning. I sense we might have to leave it to the next generation to look back and say: “We’ve had much better ways of doing this.” And we also always need new and more effective ideas. I’ve seen proposals to put 10-year term limits on Supreme Court appointments, and to give each president a couple nominations. Maybe that idea makes more sense than what we have right now. What we have right now is a disgrace.

Now for your book’s second episode, most broadly framed by the Republican Party’s departure from an honorable environmental legacy (and towards a desperate climate denialism), how does this “corruption of inaction” in fact epitomize forms of quiet intimidation immobilizing both parties on a wide array of issues: “from immigration to guns to taxes”? And how should such quiet intimidation factor into legal arguments for robust campaign-finance reform?

Right, the book lays out in some detail Republicans’ pretty honorable history on conservation and climate. They don’t have a perfect history on these issues, but certain Republican presidents and major party figures have made a point of acknowledging the dangers of environmental degradation (including climate change), and have called on us to act. The Nixon administration established the EPA, and signed into law the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. So then you can’t help sometimes asking yourself: “What happened?” How did we go from John McCain running on his climate record, to backwards climate denial emerging as the Republican Party orthodoxy? And in this book I trace that whole drift directly back to the Citizens United decision, in which the Court mistakenly believed it had to somehow “unshackle” US corporations. To me, that whole perspective seems misguided from the start — allowing billionaires to exert influence in ways no rich person had in America for decades, as some supposedly important exercise of their First Amendment rights.

That entire Citizens United decision showcased an utter misapprehension of how America’s political system and our contemporary media environment work. The Court majority focused on a narrow, narrow definition of corruption: quid pro quo corruption, where an interested party gives me something of significant cash value and then I go write a bill for them. But today’s worst corruption takes the form of a corruption of inaction. Some rich person or powerful organization threatens to spend big money against you if you act contrary to their interests.

This kind of corruption might remain invisible to the American people. But I can tell you, as a sitting Senator, that it plays a huge role in why we’ve become so dysfunctional, again particularly in Citizens United’s wake. A billionaire can rattle the coins in his or her pocket and say: “Oh really Bennet, you think you should sign on to that climate bill? You really want us to put your name on our list, and run a vicious primary against you?” So for example, when a few Republican Senators started saying, “Hey, maybe we ought to have an actual hearing and vote on Merrick Garland,” a Super PAC funded by the Koch brothers and run by a former clerk of Justice Clarence Thomas rose up and said: “Don’t you dare. Don’t you make us run a primary against you.” Those calls for a Merrick Garland hearing stopped, and the corruption of inaction again took hold.

So just to square the circle here: to get bipartisan cooperation on tackling our biggest issues like climate change, we’ll need to overturn Citizens United, so that our political system can’t get hijacked this way. And in the meantime, as we build up momentum to break from this complete misapprehension of the First Amendment’s proper place in our political system, practical steps like enforceable disclosure laws (so that every single person putting cash in our political process has to come clean to the American people about these contributions) could at least start pointing us in the right direction.

Of course, ironically, by establishing this current campaign-finance system, the Court also has made it incredibly difficult for Congress to change that system. Citizens United leaves Congress with the theoretical capacity to regulate campaign financing in ways consistent with First Amendment protections, and for the Court then to decide on the constitutionality of such regulations. But as long as billionaires can tell Congressmembers, “You better not move that bill forward…you better not try to take away our power,” this backend Court suggestion for a potential reform path seems just as implausible.

Republican failure to tap green tech’s vast economic potential points to how their “fiscal responsibility” rhetoric often clashes with the fiscal recklessness of short-sighted, self-serving, head-in-the-sand stubbornness when it comes to discredited trickle-down and starve-the-beast approaches — leaving us with huge investment deficits, the basic subject of your third episode. In an era of short-term COVID crisis, chronic economic disparities, and long-term climate concerns, which investment deficits stand out as most irresponsible?

Here I’d maybe first ask: “Where did these investment deficits come from?” They come from us, since 2001, cutting taxes by 5 trillion dollars, and borrowing that money from the Chinese. They come from us borrowing an additional 5.6 trillion dollars from the Chinese to fight two 20-year Middle East wars. They come from having a healthcare system twice as expensive per person as any equivalent country’s, but still failing so many of us. Those policy choices have created our present sense of scarcity. Those policy choices have prevented us from properly investing in our future.

You can see in this COVID pandemic’s wake the effect of those missing investments. Many people in our country have no access to primary care. Many Americans face vulnerabilities to COVID in ways that citizens of other industrialized nations do not. It has become a commonplace to say: “The pandemic has revealed so much inequity in this country.” But anybody who has spent time in America’s schools, and has seen the lack of opportunities for kids already struggling with poverty, would have a hard time being shocked right now. The results of our failing to invest enough in all American kids have been clear for decades.

I do sense us though on the cusp of a historical pivot in which we’ll hopefully return to investing in our physical infrastructure, as well as in our human capital. We need to reinvent our education systems for the 21st century, at every level: from preschool, to K through 12, to higher ed. We need to invest in a clean-energy economy that will actually drive growth and deliver wage increases, rather than the reverse. Donald Trump won an election claiming that if we deal with climate change we’ll destroy our economy, whereas if we ignore climate change, the economy will work just great. That’s obviously ridiculous. We need the opposite approach. Leading the world’s transition to a clean-energy economy will bring huge benefits to our own economy.

President Trump ran in 2016 on reinvesting in America, but has failed to do that. We have to take the opportunity to do it now. We’ll also need to figure out over the medium term some sort of glide path beyond the fiscal morass we’ve reached right now. But the good news is we can do this in coherent, constructive, non-urgent ways. We just have to stop pretending that failing to invest in America somehow proves our fiscal responsibility. In the past six months, Planet Earth has done more to wreck our country’s balance sheet, and to pile debt on our government, than most of us ever could have imagined. But that also just goes to show how irresponsible Mitch McConnell and the Republicans have been voting for 10 trillion dollars of incoherent policies when we should have been securing our future, preparing for emergencies, and paying down our debt.

Then for The Land of Flickering Lights’ fourth episode, you started off somewhat skeptical when it came to President Obama’s Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action response to increased Iranian nuclear capabilities. Could you trace the arc of thought eventually informing your decision to support the JCPOA: starting from your baseline sense of effective diplomatic solutions rarely producing some magic cure-all, and progressing towards your ultimate assessment of how Obama’s calculated risk-taking here in fact provided a “case study in leverage” (particularly when contrasted to a subsequent foreign-policy vacuum under Trump)?

I do consider Iran an untrustworthy adversary. Iran’s malevolent behavior in the region (not just their attempts to acquire a nuclear weapon, but their destabilizing activities throughout Yemen, southern Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon) should leave us all approaching any Iranian negotiations with a skeptical eye. With the JCPOA, however, I did in the end reach the conclusion that all of Iran’s nefarious activities would only get worse if backstopped by the possession of nuclear weapons, or even just the capacity to quickly assemble a nuclear weapon. The global intelligence community’s own conclusions convinced me that the JCPOA would substantially push back Iran’s breakout capability. US and Israeli and European and Russian intelligence all agreed. And in fact, until Donald Trump disturbed the deal, the Iranians did remain at least a year away from breaking out a nuclear weapon.

Before the JCPOA, Iran only needed maybe two to three months — which makes a big difference. With only a few months to spare, you might not have time to mobilize the international community to push back. Your range of motion would be much more limited. You might find yourself more inclined to see attacking Iran as your best option. And while we still do need to reserve that military option, when we have the opportunity to devise an effective multilateral effort to disarm Iran, then we definitely should pursue that.

In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, conventional wisdom on US foreign policy said you shouldn’t engage your enemies through sustained diplomatic negotiations. But Barack Obama had run for president saying that he would engage the enemy in negotiations when this served US strategic interests. That already represented a shift. And the second piece of effective negotiations here came from mobilizing much of the world to support our efforts. Almost every country endorsed the JCPOA, and the P5+1 multilateral negotiations included Germany, France, the UK, China, Russia, and others.

That all stands in stark contrast to President Trump’s chaotic foreign policy, which has dangerously undermined America’s global standing. Over and over again, Trump has shown himself willing to play footsie with dictators (while directly alienating and insulting many of our most critical allies). I can’t imagine any previous president allowing Vladimir Putin to play him for the rube or the patsy in ways that Putin has played Donald Trump. The same could be said for Xi Jinping. I sense that the Iranians, the Chinese, and the Russians would welcome Donald Trump winning reelection, allowing them to keep pursuing their geopolitical ambitions in this vacuum of global leadership President Trump has created — all at the expense of the US and our allies.

For your book’s fifth episode, I found especially interesting how citizen perspectives on immigration often get shaped by countless localized conditions and constraints, again with Americans often tapping their knack for pragmatic compromise. But I found equally relevant the idea that every single parochial perspective on immigration has little chance of adding up to coherent policy. So how did the process of hashing out the Colorado Compromise inform your approach to this basic tension, first on state-wide and then on national levels?

Well I probably should acknowledge that this Colorado Compromise first emerged as something of a rip-off.

Of the Utah Compact.

Exactly. Utah’s Republican attorney general, who had significant concerns about the direction of our immigration debates, had forged what he called the Utah Compact. I saw that and thought: Well, that approach sounds interesting, and our immigration debates worry me too. I’d sensed that all of our demagoguing around immigration had run the risk of making any substantive immigration reform impossible.

So I basically traveled the state of Colorado, and heard out as many Coloradans as I could. I always feel especially lucky to represent Colorado, a state one-third Democrat, one-third Republican, and one-third independent. I always appreciate learning what people across our state think about a wide range of complex issues: from immigration, to guns, to police reform right now. Listening to Colorado residents, I feel I get this advanced preview on where the whole country’s heading.

Overall, I took away from this experience that we had a lot more agreement than disagreement on the fundamental points of immigration reform. The strongest skepticism I encountered took the general form of: “Well, if we work on your priorities, then I sense we’ll never get to my priorities.” So the most pressing questions seemed to revolve around how to address multiple concerns all at the same time.

In the Senate, we tried to answer those questions by putting together the Gang of Eight. And when I look back to the Gang of Eight effort, I still think we got out basic process for effective governance right. I sense that most of our fellow Americans don’t obsess over politics. Most Americans don’t spend their days and nights reading political websites and writing to their elected representatives. Most of us spend much more time trying to make sure our kids can attend a decent school, or building up independent businesses, or doing something useful for our communities, or neighborhoods, or churches or synagogues or mosques.

Most Americans probably have the expectation that our federal government should function like it did in that old Schoolhouse Rock! cartoon about how a bill becomes a law [Laughter]. I actually consider that a very reasonable expectation. The American people don’t ask for some biblical level of leadership, some heroic level of leadership. They basically tell those of us in Washington: “Just take up the responsibility to do the work we sent you there to do.”

Unfortunately, virtually nothing I’ve been a part of over the past decade in the Senate has measured up to that Schoolhouse Rock! standard, except for the Gang of Eight bill, where we deliberately started with four Democrats and four Republicans, representing different generations in the Senate, representing different regions and geographies — some suburban, some rural, some urban. We all had our different perspectives, but we shared the commitment to reach a result creating pathways to citizenship for the 11 million undocumented people in the US at that time. That was the only real price of admission. You had to possess this sense that we just couldn’t let the American people down by failing to address that one complex issue. But everything else was open for debate.

I believe our pluralistic decision-making process would have made the Constitution’s framers pretty proud of their institutional architecture. Instead of imagining that any one of us held a monopoly on wisdom, or that the eight of us had to arrive at some shabby compromise right smack in the middle of our two parties’ obsolete ideas, we actually believed that together we could create something more energetic, more imaginative, than any one of us could have devised on our own. So we did just that.

This Gang of Eight proposal proactively addressed a Republican sore point about preceding “amnesty” measures not in fact reducing our large number of undocumented immigrants much. It operated from a basic assumption that “unless we secured the border, we would never stem future flows.” It embraced a points system “allocated by education level, English-language level, family ties, and work experience.” All of that sounds reasonable to me. But how would you make this case today to those progressive Democrats who might consider any emphasis on enhanced border enforcement (or any dilution of family-based determinations) hypocritical or inhumane?

First I wouldn’t expect any bill today to have those exact same 2013 parameters. The bill will have changed as a result of what we’ve seen in intervening years — not the least of which has been this terrible separation of families at the border and in other places. We also have many, many more people incarcerated today, as a result of our immigration system, than we had in 2013. So as in any case really, we first would have to update the legislation for today, and take account of how the world has changed, which here means taking account of the Trump administration’s brutal immigration policies.

Having said that, it did seem quite clear to us that we couldn’t get a good bipartisan bill or positive long-term results on immigration policy if we couldn’t confidently tell the American people that this legislation would make our borders much more secure. We chose to secure US borders with 21st-century technology, not with some medieval wall that Donald Trump will apparently get Mexico to pay for. We had nothing like the Trump administration’s approach to using ICE as this amplified internal-security force.

I’d also say that protecting Dreamers and their families must remain central to any negotiation. In 2013, the Dreamers’ bottom-line message to us was: “Don’t ever ask us to accept anything happening to our parents that you would never accept happening to your parents.” I would see that important non-negotiable point extending quite far into any further compromises on immigration.

So to close then more broadly on prospects for future problem-solving, given your sense of three basic options for our most pressing policy challenges (do nothing constructive and just hope crises disappear, treat governance as a partisan fight to the finish, or return to pluralistic decision-making mechanisms created by Constitution framers and subsequent founders), how could we all come to see this last approach less as a retreat from, than as a necessary rekindling of, America’s basic promise?

For me, the progressive fight always has been a fight to make this country more democratic, more fair, more free. That always has meant making this country more pluralistic. That always has meant expanding people’s chances to participate in democratic self-governance.

Today, far too many Americans can’t flourish or participate effectively in our democracy, because they lack adequate primary healthcare, or because they have no real chance to get a decent education, or because we just haven’t built the infrastructure that would allow them to access the Internet in ways most of the industrialized world has come to expect, or because we’ve never resolved their immigration status. I mean, that just points to a very few of the barriers people face right now. That doesn’t even begin to address elected officeholders actively suppressing the vote in this country, actively making it even more difficult for their fellow Americans to participate in our democratic society.

But when I think back to what my grandparents (Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust, and came to the US to rebuild their shattered lives, in the only country where they believed they could do that) loved about this idea of America, they never conceived of America as a perfect place. Even in their distress, they always recognized America’s own imperfections, and American citizens’ own opportunities and in fact responsibilities to forever improve this country, and to reinvigorate its fragile experiment in democracy, and to show the whole world what those democratic commitments could accomplish.

For me, our role as citizens of this republic starts right there. If we instead hold out hope for some kind of preferred one-party rule, we ignore the dialectical nature of this democratic experiment our framers designed. We ignore the (at times, no doubt, quite challenging) historical conversation between our worst impulses and our best instincts. We deny ourselves the opportunity to build on this pluralistic approach to create a set of 21st-century policies driving democratic participation far and wide.

Again, I wrote this book as a former superintendent for an urban school district. And I believe we’d be a lot better off thinking about all of our kids not as potential future presidents, but as inevitable future founders. They are the people we will rely on to carry this democratic tradition into the next generation, and to build America’s democratic future for further generations, and to fortify America’s place in the world. If we thought of all American kids as founders in this way, we’d actually make our democracy far stronger.

Portrait of Senator Michael Bennet courtesy of Bernard Grant.