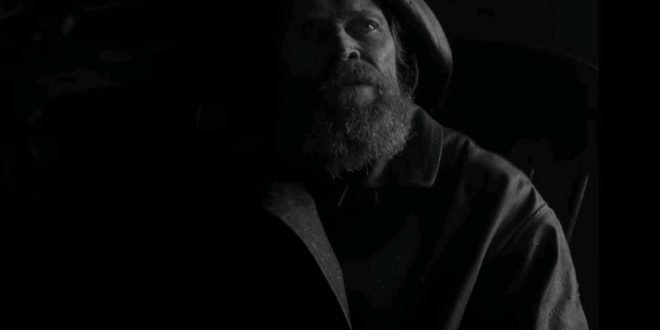

The lamps sway; the clock is stopped. A violent tempest shrieks and sprays as if it will tear through the very fabric of the screen. Anxious howls sound around the unstable inhabitants of the rock. There is slime, sludge, wetness. Everything is drenched and slowly eroding into the sea, sucked decaying back into the island.

Like opening a cursed can of celluloid dug up from the wet earth and unleashing 19th-century gothic in the present day, The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers) is a self-certified and critically acclaimed horror film that has taken audiences by storm. Yet there are no zombies, vampires, or masked men stalking unwitting teens in the dark as lighthouse keeper Thomas (Willem Dafoe) and assistant ‘wick’ Ephraim (Robert Pattinson) attempt to ride out a squall that cuts them off from their supplies. This makes The Lighthouse an unusual entity, especially in a cultural landscape averse to identifying genre films (Get Out, for example, was infamously nominated in the comedy category at the 2017 Golden Globes). Nevertheless, despite eschewing many typical horror conventions — there are no Midsommar-esque pagan rituals or Us-like underworld doppelgängers — Eggers’s nautical tale features a no less disturbing creature of darkness. For The Lighthouse makes its monster the monster of relentless, unabating capitalism — and it’s a monster from which there is no escape.

Arriving on an isolated outpost of Atlantic rock sometime in the 1890s (location filming took place at Cape Forchu, Nova Scotia), Ephraim prepares to spend four weeks working under the tutelage of experienced lighthouse keeper Thomas. From the outset, there is trouble brewing: Ephraim experiences strange visions of a mermaid and a tentacled creature, and a storm erupts shortly after he murders a seabird against Thomas’s folkloric advice. Cut off from the labor and ration relief due to reach them from the mainland, the two men are duty bound to maintain the never-ceasing, always turning, fuel-guzzling lamp, even as their own lives descend into chaotic darkness.

Their situation on the lighthouse is marginal and their existence is precarious. However, they must serve the countless unseen ships (other signs of life remain invisible throughout the film) that carry the spoils of empire across the ocean. Somewhere beyond the horizon the wicks are enabling the global expansion of the Hudson Bay Company, a British trading enterprise that violently exploited indigenous lands to profit from the sale of fur and lumber. Similar firms carry tobacco, lumber, and luxury goods between Europe and North America while passenger ships ferry tourists and immigrants — all part of an invisible imperial project that requires constant light, and constant attention from the wicks. Ephraim may have left his job as a logger for Hudson Bay, but on the lighthouse, he vicariously serves and enriches the same master. There is no getting away from it. As the two men struggle and squelch in the filth of the squalid lighthouse, they accumulate wealth for a handful of male individuals who wield power in the industrial age.

Both men, therefore, are proximate to and distant from the mechanisms of capitalism. They literally feed the corporate leviathan when they haul canisters of kerosene up the lighthouse steps to satisfy the lamp, and yet they are also what Eric Hobsbawm calls “the labouring classes” — they are “too poor to provide an intensive market for anything but the absolute essentials of subsistence: food, housing, and a few elementary pieces of clothing and household goods.” Ephraim and Thomas are essential and inessential; on the lighthouse they exist in what I call an apotopia. Derived from Foucault’s heterotopia (an “other” space that both passes through and is passed through — for example, a train carriage, or a graveyard), the apotopia is a site from which one looks down or overlooks, while also being overlooked or looked down upon. Thomas uses the phallic height of the apotopian lighthouse as a vantage point, and in lighting the lamp, the men participate in a system of imperial navigation and surveillance (what Benedict Anderson describes as a “human landscape of perfect visibility”). However, the same system simultaneously neglects them and leaves them to die when the storm arises. Both seen and unseen, their visible mortal bodies are grotesque and hidden from the outside world, while the fruits of their invisible labor — the light — radiates out as a beacon of continuity and safety for capitalist transaction.

It is the lure of the lamp and the power it represents that hastens the wicks’ demise. To paraphrase Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, capitalism haunts all forms of society, and it haunts Ephraim and Thomas as their terrifying nightmare. Ephraim wants to literally and metaphorically rise above his station, to be close to the lamp and its brilliance, even at the expense of his superior. He sees the feminized work of what Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall refer to as the “private sphere” — that is, the domestic environment of the home — as menial, cheap, and undignified in his patriarchal pursuit of power. He curses Thomas’s womanly knitting and rejects chores that involve cleaning or mopping. Meanwhile Thomas functions as a manager, part of a highly masculinized surveillance network of logbooks and bureaucracy, and his lies about his colleague’s aptitude for work make Ephraim ever more precarious. Pitting themselves against one another to control the lamp and prove themselves the better laborer, the monster of capitalism drives them mad with jealous rage and a futile desire for power that serves neither man.

Indeed, as the men slowly ooze into the gross damp slime of their surroundings — this is a film awash with blood, shit, piss, and cum that ebbs like life itself from their broken bodies — they are physically and mentally destroyed by the conditions of their work. Ephraim, whose name means fruitful, fertile, productive, is driven slowly mad by a combination of Thomas’s unnatural tales (nature is a brutal, if secondary, foe) and the drudgery of unskilled labor. Eventually, he finds he can no longer labor as a man. Rubbing at the carved wooden breasts of a mermaid figurine while he masturbates, he gives himself up as impotent and unable to function as either himself or a useful agent of (re)production. He suffers a stress-related mental health breakdown, perhaps not dissimilar from the psychological effects of Railway Spine, a diagnosis that Victorian doctors gave patients experiencing trauma after exposure to trains (Ephraim is, after all, responsible for the screeching mechanics of the lighthouse). But his condition and its true cause is immaterial. As Thomas suggests: the horrific nightmare of slow starvation and endless labor might be real. Or it might all be a hallucination, a dream you’re having as you lie broken in a forest working for Hudson Bay.

Either way, Ephraim will be just another shattered body, another ghostly statistic in a logbook that doesn’t care how many men it takes to feed the monster. And therein lies the greatest horror of The Lighthouse: the final terror inflicted by capitalism. Thomas and Ephraim may be white men, but they still don’t matter. Of course, there are no black people or indigenous people or even real human women in the film. Those who ultimately shoulder the burdens of capitalism’s harshest violence are absent, because in the most horrifying fiction as in real life, no one really cares about their stories. The men do configure the lamp as “she,” an all-consuming female presence that demands constant attention (kerosene, paint, repairs) and is a potent symbol of desire. Low-angle shots tilt up and down the length of the lighthouse’s body, objectifying the phallic mistress like a mythical siren that lures men to their deaths. Alongside the mermaid that haunts Ephraim’s dreams, the queer space of the lighthouse is what Barbara Creed would call the “monstrous feminine”: it is both the womb that protects the men from the storm and the maddening, hysterical monster that castrates them. The monstrous feminine, the monster that consumes and expands and yet does not expend its own energy in doing so, is always a woman. And the woman is always configured as the worst excesses of capitalism.

Thus, The Lighthouse works on slippery layers of dirt and filth and mud to horrify its viewers.

As indigenous scholar Audra Simpson describes, settler nations like the US and Canada often attempt to “escape the ugliness of history.” However, haunted always by capitalism, viewers cannot untether the lighthouse inhabited by Thomas and Ephraim from its (or indeed, their own) role in colonial violence. The film also speaks to our own systems of oppressive employment, of long hours and low pay and mind-numbing low-reward labor. And, in returning us to the period of industrialization that set the current climate catastrophe in motion, the film’s bleak ending reminds us that we, the 99%, are always working toward our own inevitable destruction. The two white men at the heart of the story insist on their own inglorious sacrifice to feed the Moloch-like lamp: they are responsible for their own demise.

To think that all Thomas and Ephraim had to do was set down tools, stop working, and refuse to feed the lamp in order to be seen and potentially saved. But that is the final and defining horror of a cultural and economic system that binds us in its steady and destructive rhythms. In the end, The Lighthouse is a film that haunts us with a decisive, if disturbing, reflection of nothing more than ourselves.