Leonora Carrington’s stories are whimsical nightmares in the spirit of the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. A man rides a happy cadaver to search for his lost love. A hyena kills a maid and wears her face to a fancy ball. A priest gifts a pork chop to a woman during a game of bridge. “The chop, which had undoubtedly spent a very long time near the ecclesiastic’s stomach didn’t appeal to me,” the woman says. It oozes “horrible blobs of grease” between her fingers, and she sneaks out to the yard to try (unsuccessfully) to bury it.

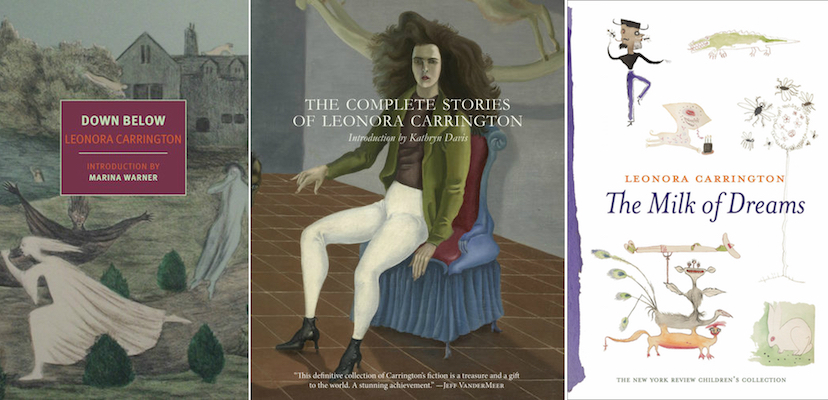

Leonora Carrington is perhaps best known for her surrealist paintings — though this is subject to change — which are also alive with lurid charm. Carrington died in 2011 at the age of 94, but this year, on the centennial of her birth, her books are coming back strong. The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, published by Dorothy, brings together all of Carrington’s stories for the first time, and the New York Review Books also recently published Down Below, a feverish memoir about Carrington’s time in a mental institution. In May, we’ll see The Milk of Dreams (also from New York Review Books), a children’s book that combines Carrington’s painting and prose.

Carrington lived many lives in her 94 years, and her biography is difficult to pin down. She was born to a wealthy family in England, but also lived in France and Spain, and then spent most of her life in Mexico City. She wrote in both French and Spanish. She married the German painter Max Ernst, later the Mexican poet Renato Leduc, and finally the Hungarian photographer Emerico Weisz (though her most important partnership may have been with fellow female surrealist Remedios Varo).

In the introduction to Down Below, Marina Warner writes that Carrington was an artist of internal division and that she rejected the notion of a unified, artistic identity. “This is the paradox of her personality as well as her oeuvre,” Warner writes. “In her very denials of so many of the foundations of Western ideas about sanity and the unified self, she comes near to fulfilling deeply shared Western longings for Original Genius.”

One of the many virtues of Carrington’s writing is the unhesitating momentum of her freakish scenarios and her refusal to slow down for rationale. The extravagances of Carrington’s characters tend to fulfill simple and self-indulgent ends. Take Igname the Boar, who enjoys decorating himself with fruits, leaves, plants, and necklaces of little animals, “which he killed solely to make himself look elegant, since he ate nothing but truffles.” In “A Man in Love,” the narrator visits a fruit seller and his catatonic wife and listens to the man’s tragic story, just to steal a melon and disappear once his tears blind him. In “The House of Fear, a powerful mistress wears a dressing gown made of live bats sewn together by their wings: “The way they fluttered, one would have thought they didn’t much like it.”

Carrington’s life was packed with sinister touches that weren’t terribly far from the spirit of her stories. She grew up on a wealthy estate that she found absurd and suffocating, and she railed against it (she was expelled from two different schools as an adolescent). She was indifferent to others’ reactions to her sexuality and nudity, and fairly unshaken by the sometimes-extreme violence that surrounded her. She calmly worked on a farm and basked in the sun while Belgium collapsed and the Nazis invaded France. “I had no fear whatsoever within me,” Carrington writes in Down Below. “Some soldiers who had entered my home accused me of being a spy and threatened to shoot me on the spot because someone had been looking for snails at night, with a lantern, near my house. Their threats impressed me very little indeed, for I knew that I was not destined to die.”

One of the startling elements of Down Below is observing a seemingly imperturbable person break down, in part on her pathway to the mental hospital, but more so in the institution itself. Carrington’s doctors repeatedly inject her with a powerful drug that treats depression but also causes uncontrolled seizures. “I burst into tears,” Carrington writes. “[The doctor] took my by the arm, then, and I realized with horror that he was going to give me my third dose of Cardiozal. I promised him all that was within my power to give if only he would desist from giving me the injection.” She remembers her prior doses — her inability to move, being crippled within her own “horrible reality.” He injects her anyway. Carrington writes, “[He] was not a sorcerer but a scoundrel.”

A distant cousin and doctor rescued Carrington from the asylum. In 1942, after brief stints in Portugal and New York, Carrington went to Mexico, where the socialist government offered citizenship to refugees of fascism. Warner writes that many surrealists gathered in Mexico City, a place that — with its mythic past, cult of the dead, and astonishing landscapes — was surrealist in itself. There Carrington wrote stories about trained rats who can perform surgery, a cow who mothers humans, a woman who lives on a traffic island, and a midwife who seals a greedy man’s orifices up with red zip fasteners.

Other than The Hearing Trumpet — republished by Exact Change in 2004 — Carrington’s books haven’t been easy to get in English for the past several decades. Thanks to Dorothy and New York Review Books, this is the year we regain access to the work of a brilliant madwoman and readers will find delight in her sinister touch. Carrington gleefully escorts her audience through darkness and madness. “Do you know that I can hate for seventy-seven million years without stopping for rest,” Carrington writes. “Tell those miserable people that they are doomed.” Carrington’s writing is a hellish playground, and being doomed by her turns out to be a lot of fun.