For 1,500 years, readers have been captivated by stories of travel. In 440 AD, the Greek author Herodotus journeyed all over the Mediterranean Levant describing everything from Egypt’s pyramids and landscapes to unscrupulous souvenir vendors. In 1869, Mark Twain toured the medieval reliquaries of Europe and wrote his famous travelogue, The Innocents Abroad. (“As for bones of St. Denis,” Twain quipped, “I feel certain we have seen enough of them to duplicate him if necessary.”) And, of course, Marco Polo’s journey across the Silk Road and throughout southeast Asia, as told in his 13th-century Travels, is a historic archetype of the genre.

Travel writing seems so simple — an audience is introduced to a specific part of the world through a specific impetus for a journey. Most travelogues follow a simple structural schema of encounter, encountered, and mediated experience. Travel readers have come to expect a similar pattern, then: the narrator comes, they do something, they leave. It’s only the details that differ.

At the heart of travel writing, then, is the assumption of narrative authenticity — the belief that the narrator is guiding her readers, Virgil-like, through unfamiliar parts of the world and telling readers, as truthfully as possible, what the traveled experience is like. It’s up to the narrator to negotiate the traveled experience with readers’ familiarity and expectations and the authenticity of a writer’s experience depends on how believable audiences find the telling of the narrative. The audience has to believe what they’re reading is actually true.

But what if a fictionalized travel account could be even more true than a traditional travelogue? What if the imagined could be more authentic than something strictly factual?

¤

When Italo Calvino published Invisible Cities in 1972 (the English translation was published in 1974), the short novel challenged that very narrative authority so associated with the idea of reading about travel. For one thing, Invisible Cities was fiction and didn’t pretend to be anything else. For another, it asked its readers to consider the possibility that a traveler might not have to actually go to a city to write about it. Calvino’s novella suggests that the believability, authenticity, of a narrator is a construct of travel writing expectations — whether or not a narrator actually went to the places described ought not to impact how much the reader believed Calvino.

Invisible Cities is written as an imagined set of conversations between the famous traveler, Marco Polo, and the emperor of the 13th century Mongolian empire, Kublai Khan. Kublai has tasked Marco Polo with exploring Kublai’s vast empire (historians estimate that Kublai’s empire could have covered roughly one-fifth of the inhabited land on earth at its height) and report back to him about the cities, peoples, and things that Marco Polo sees. “Kublai Khan does not necessarily believe everything Marco Polo says when he describes the cities visited on his expeditions,” Calvino opens with in Invisible Cities, “but the emperor of the Tartars does continue listening to the young Venetian with greater attention and curiosity than he shows any other messenger or explorer of his.” This is an implicit challenge to the canonical place of Marco Polo’s Travels in the history of traditional travel literature. “We will set down things seen as seen, things heard as heard, so that our book may be an accurate record, free from any sort of fabrication,” Marco Polo and his co-author Rustichello of Pisa, a romance writer of some repute, claim in the Travels’ prologue. “And all who read the book or hear it may do so with full confidence because it contains nothing but the truth.”

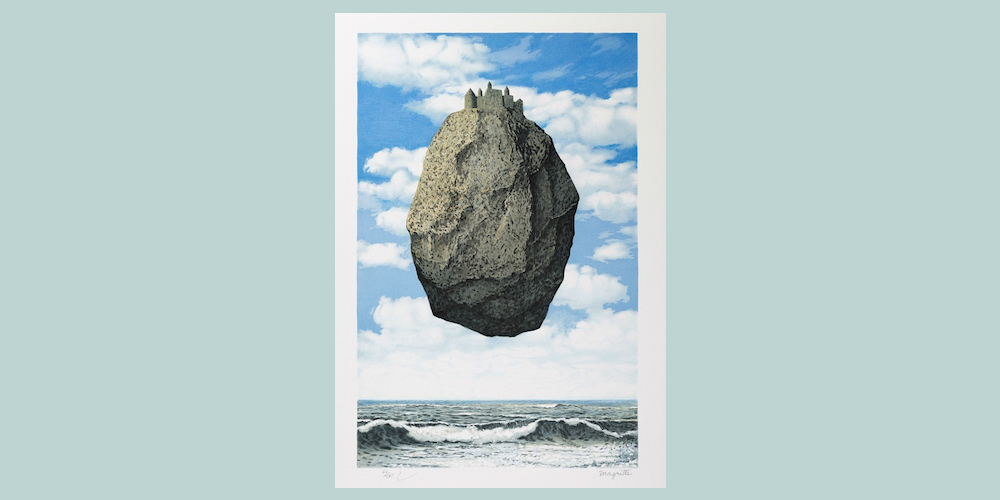

In Calvino’s imagining of Marco Polo’s travels, Polo describes 55 cities to Kublai Khan. Calvino’s Marco Polo describes each fictional city — like Ersilia, Olinda, and Laudomia — with lyrical curiosity, almost as if each city was a riddle for his audience to work out. (“Now I shall tell of the city of Zenobia, which is wonderful in this fashion: although set on dry terrain it stands on high pilings, and the houses are of bamboo and zinc, with many platforms and balconies placed on stilts at various heights, crossing one another, linked by ladders and hanging side-walks surmounted by cone-roofed belvederes, barrels storing water, weather vanes, jutting pulleys, and fish poles, and cranes.” It’s like Calvino is writing about about Ewok settlements on the planet Endor decades before that was a real-fictional thing…) The city of Despina can only be reached by ship or by camel. All of the beauties of the city of Diomira will be familiar to the visitor, Marco Polo explains to Kublai Khan, since they will have been seen in other cities. Calvino’s Polo builds impossible complexities, fascinating juxtapositions, encouraging readers to buy into the authenticity of his narrative by encouraging his audience to doubt it. It didn’t matter if the city of Zemrude was real or not — Marco Polo’s description of a city with narrow streets, window sills, fountains, and flapping curtains allows a reader to fill in the blanks for a city that could be like Zemrude. (The novella has also inspired a plethora of artists, as highlighted last fall, by Literary Hub.) Thus, cities are simply symbols, icons, and touchstones of human emotions; they aren’t necessarily tangible, physical places.

When he arrived at the city of Trude, for example, Marco Polo thought he had landed at the same airport that he had departed from. The suburbs he visited were the same as the previous city; the flower beds identical; the stores sold the very same goods, advertised in the very same ways. “This was the first time I had come to Trude, but I already knew the hotel where I happened to be lodged,” Polo describes. Then why come to Trude at all, he wonders. “You can resume your flight whenever you like,” the Trudians said to him, “but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same, detail by detail. The world is covered by a sole Trude which does not begin and does not end. Only the name of the airport changes.”

Any reader who has spent any time numbed-out in the global cacophony of air travel finds themselves nodding in agreement at Calvino’s lyrically poignant observation — all of world’s the airports are really the same. You come, you wait, (maybe) you get to leave, but you’re just going to go sit and wait in the same airport all over again. The narrative authenticity of Invisible Cities — why readers buy Calvino’s account of Marco Polo in an airport as believable — is because of how authentic the metaphors for each city are. And how is each fictional city modeled?

“And I have constructed in my mind a model city from which all possible cities can be deduced,” Kublai said. “It contains everything corresponding to the norm. Since cities that exist diverge in varying degree from the norm, I need only foresee the exceptions to the norm and calculate the most probable combinations.”

“I have also thought of a model city from which I deduce all the others,” Marco answered. “It is a city made only of exceptions, exclusions, incongruities, contradictions. If such a city is the most improbably, by reducing the number of abnormal elements, we increase the probability that the city really exists…But I cannot force my operation beyond a certain limit: I would achieve cites too probable to be real.”

¤

I read Invisible Cities while traveling around Mongolia last fall, wondering if the ancient city of Karakoram was Calvino’s model for the city of Aglaura (a city “planted at random”) or if Sophronia, made up of “two half cities,” could be Mongolia’s capital Ulaanbataar, a way of reconciling a city built so episodically throughout its history. I leaf through my copy of Invisible Cities now and there is sand from the Gobi pressed into the spine and a candy wrapper with Cyrillic script marks one of the chapters. Every time I revisit the Calvino’s imagined cities, I know I’ll be revisiting my experience of reading a fictional account of traveling to places Marco Polo went — just not Calvino’s version of Marco Polo.

Invisible Cities was nominated for a Nebula Award in 1974, thanks to the ways its deep questions of authenticity and experience resonate with all travelers and all travelogue writers as they seek to describe what experiences are real, what are not, and what are in-between. The narrative power of Invisible Cities lies in its ability to celebrate that which is in-between. At the end of Invisible Cities, the reader is left wondering whether Marco Polo had ever traveled anywhere. And then wondering if it even matters whether he did or not. It’s hard to imagine a more authentic travelogue than Calvino’s work of fiction.

The next time a friend of mine is traveling anywhere, I’ll recommend they bring along Invisible Cities — it doesn’t matter where they’re going or what they are planning to see. Calvino will have already described it.