The year is 1907 and a medical director at a clinic in Temperley, Argentina — a province of Buenos Aires — presents a French study to his colleagues. The proposition of the study in short: the human head remains conscious with full use of its faculties for nine seconds after decapitation. The tradition of an executioner holding the head aloft after chopping it off is only in part for the audience. It is also for the decapitated head — providing it the final spectacle of the cheering crowd.

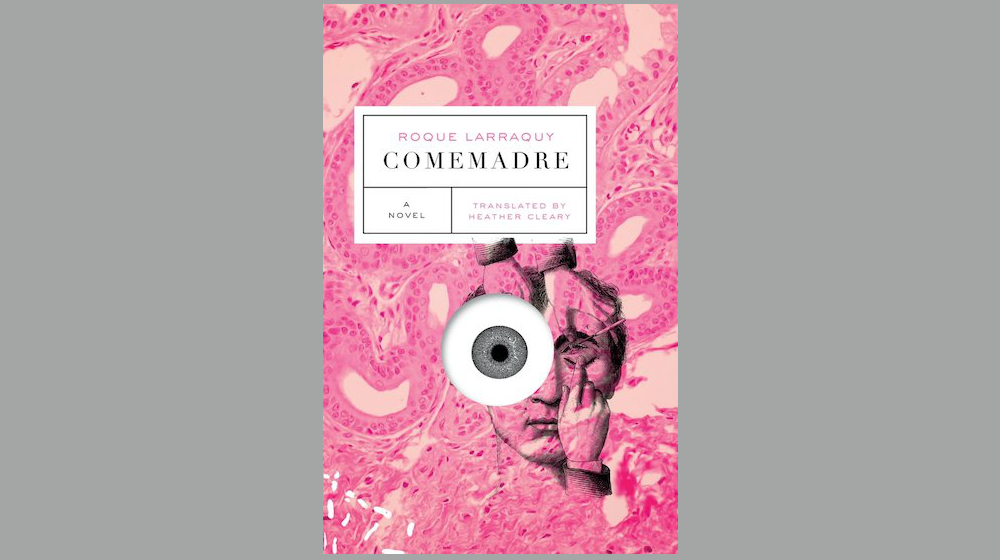

This French study — with no facts or references, as one colleague points out — is the occasion for Argentine writer Roque Larraquy’s Comemadre. Translated by Heather Cleary, this is Larraquy’s debut novel in English and it arrives like a shockwave. It has already earned the wonder and admiration of contemporary horror stars like Brian Evenson and Samanta Schweblin. Schweblin writes, “Here I am, days after reading it, still asking myself what kind of book it is. Is it humor? Horror? Is it about art? Science? Philosophy? One thing is certain: it is just the kind of book that you’ll want to recommend to your friends over and over again.”

The nearly indescribable approach is part of the fun of Comemadre, especially given the confidence and poise of its delivery. “This is what I propose,” the medical director says to the room. “We select a group of terminally ill patients and sever their heads without damaging their vocal apparatus […] We then ask the heads to tell us what they observe.” In the perspective of despicable Doctor Quintana, we carry out this absurd and horrifying experiment.

While the characters in Comemadre sometimes pause to hesitate over the ethics of persuading their patients to consent to a life-ending experiment, they all tend to err on the side of science, or at least improving their own alpha standings in the sanatorium. Each man in this story is also smitten with Nurse Menéndez; in the competition to see who can secure the most volunteers, the competitors care less about the professional bonus than the opportunity to impress their crush. “We’ll go out to dinner once a week. And to the opera,” Quintana says to Menéndez in one of the sections that resembles a scrappy love letter. “When no one’s around, I’ll nibble your backside. I’ll give you a stole to cover your neck, and you’ll remove it only for me.”

But the desperate and sweaty-palmed pursuit of Menéndez acts as more of a fuel than a distraction for their mission, and incredibly, the experiment works. One decapitated head says, “Welcome,” and another “Just like I dreamed.” The heads say, “He doesn’t love me,” “Children last,” and “No eyes or nose, but a mouth.” Not all of the chopped heads speak, but most of them do. Each time you think the experiment has reached a feasible end, it continues. Before long, the doctors feel that nine seconds is too short for proper analysis. Quintana reveals his new vision to his colleagues: “Multiple devices, in a circle. Donors looking at one another. The guillotines activating sequentially, every nine seconds. Each head picking up where the last one left off to make a full sentence, a paragraph […] A string of words worth the expense and efforts of this team.”

To startling effect, this already-short novel reaches a surreal and sudden end when it abruptly splits, launching us to Buenos Aires in 2009 into a new story about the moral and bodily limits of the contemporary art world. The two sections are connected by, among other things, Quintana’s great grandson Sebastian. Sebastian has inherited a variety of his great grandfather’s possessions, including notes and manuscripts and vials of the black powder of the title plant. This plant’s sap produces anomalous microscopic animal larvae that can make a body digest itself. As it’s explained in the book, the Spanish name for the plant died out in Patagonia years ago, but it lives on in England as motherseeker or mothersicken. In the sanatorium in 1907, Quintana used it to successfully address the problem of the pile of bodies generated by the experiment. Quintana’s great grandson uses it again, in a way that again goes beyond what we once thought feasible. Comemadre shocks on each page, and it’s also very funny. It is absurd and straight-faced and frighteningly self-assured.

The characters in Comemadre can be a lot to stomach; the doctors are xenophobic misogynists who talk of eugenics. The artists are self-saboteurs and pain-seekers. They are almost all egomaniacs. But in pursuit of their madness and defense of their image, these characters tend to end up under the knife themselves. In the first section, one researcher insists very quickly on participating in the experiment; they accidentally bobble his head post-decapitation, muting his final speech. In the second, two artists can’t agree on which should get facial reconstructive surgery so they look exactly the same. They finally agree what’s most fair is to choose a third face to imitate, and both have their noses readjusted and skulls shaved.

Part of the horrifying joy of this novel is how safely you can rest in the hands of a maniac as the narrative world is built and burned down around you. In a scene in the first story, we encounter Quintana persuading a patient to consent to the life-ending experiment. The man is of Italian descent and Quintana explains that Mother Nature is wise and it had endowed southern Italians with high levels of potassium. Unfortunately, he says, the potassium affects the chemical structure of the serum (a placebo) they had used to try to fight the patient’s cancer. Quintana is clear and confident, and the patient agrees to the experiment. “The patient doesn’t understand,” Quintana says, “but it’s enough for him that I do.” No reader would be able to know where this story is going. But it’s enough that Larraquy does.