The story circulates like a gift; an empty gift which anybody can lay claim to by filling it to taste, yet can never truly possess. A gift built on multiplicity. One that stays inexhaustible within its own limits. Its departures and arrivals.

—Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other

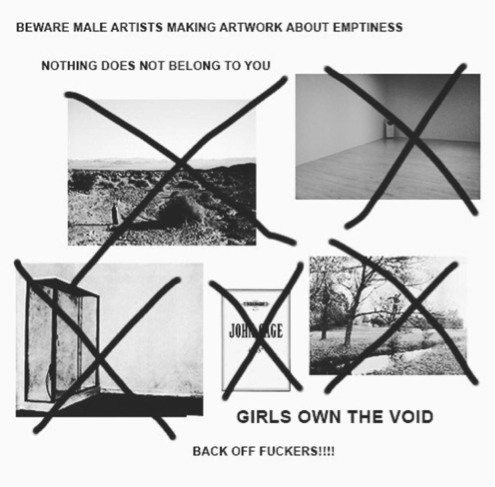

In 2015, Audrey Wollen posted a meme declaring “GIRLS OWN THE VOID.” She crossed out black and white images of works by celebrated male artists. “Beware male artists making artwork about emptiness,” warned the meme. Beneath its cheeky territorialism was the presupposition that “girls” have an altogether distinct vantage from men, one that is uniquely suited to seeing and expressing the void.

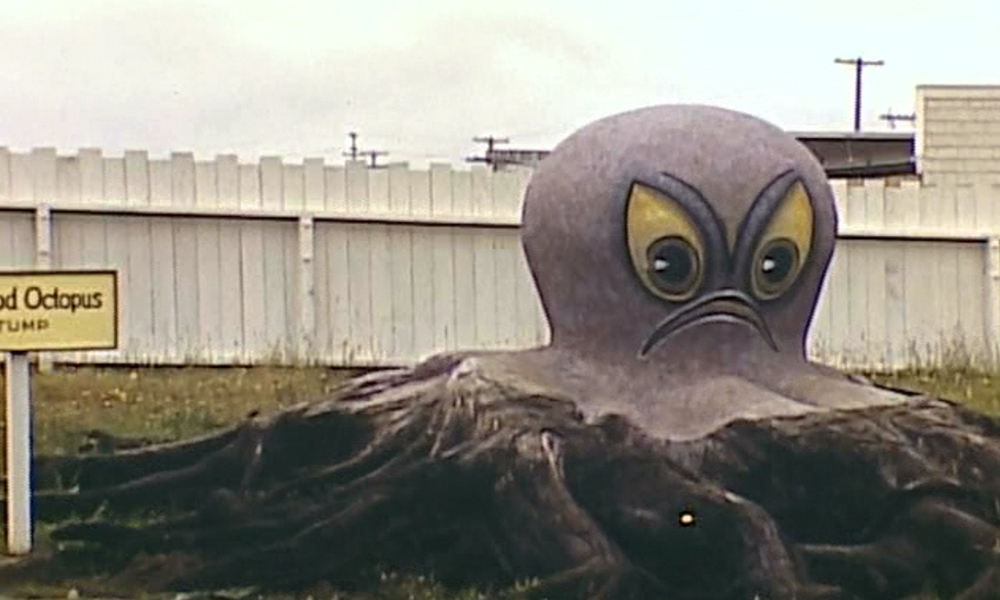

The question of a female gaze and if one exists at all gives shape to Courtney Stephens’s stunning Terra Femme (2017 – 2021), which debuted March 29 – April 3 through the Museum of Modern Art’s online presentation of Doc Fortnight 2021. In 2017, the Los Angeles-based filmmaker began presenting iterative lectures to share her research on American and British women’s travelogues made between the 1920s to 1950s. Freezing and formalizing these live presentations for a post-pandemic world, Terra Femme weaves through archival footage that varies tremendously not only in location, but in the identities and possible motivations of its amateur creators. Stephens narrates her chosen images with a mixture of poetry and fact that is both wandering and rigorous, confronting complex entanglements of daily life, gender, technology, and imperialism. As she asks, “What does the narrative of exploration offer women?” Stephens frames her own journey with self-reflexivity, hunger, and a crystalline refusal to pin any subject down.

What can and cannot be seen, described, recorded, or otherwise located is of central concern. The film opens with disappearance: explorers lost while searching for the Northwest Passage in 1845. Illiterate female clairvoyants, Stephens tells us, were hired in an attempt to locate the men, paid to travel in their minds to a place their bodies would likely never go. In the hour that follows, Stephens enacts a gentle unspooling of parallels between geographic and psychic territory. She reveals that her own two-year excursion to India was propelled by the discovery of “blank” spots in her brain, a medical condition that could have led to full-body paralysis.

Filling in so-called blank spots on the map has been a central task of imperialism, that force which runs so uneasily through the discipline of anthropology. Stephens names this violence plainly even as she grapples with the coordinates of women behind their cameras. There is Ursula Graham Bower, whose study of Naga tribes led directly to their conscription as British soldiers. Or Nancy Kendall, documenting daily life in colonial India as the wife of an English officer — what Stephens, borrowing from Hannah Arendt, suggests as the “banality of empire.” Captive elephants bathe in chains, a severed tree is hauled away on a truck. Percolating beneath it all is the question if freedom can exist without violence — Stephens laments, “You go looking for documents of female freedom and find other forms of domination.”

Such “accidental ethnography” folds smoothly into Terra Femme’s considerations of crossings and ritual. Like cinema, ritual unites bodies both to specific time and place and to bigger stories that continue to unfold. Reflecting on the American road trips of Armeta Hearst and her husband, a black couple traveling through a segregated country, Stephens offers, “Archives reflect not only what people did and what they saved, but what it meant to cross the threshold.” The thresholds of Terra Femme are innumerable — the doors of neighbors, the Arctic Circle, the women-only wedding ceremony, the divorce, the funeral procession, life and death, here and there, before and after, past and present. Post-colonialism is no exception, and Stephens recognizes a sense of loss even amidst colonial benefactors, deprived their experience of virgin realms: “A nostalgia for the original nostalgia had taken hold,” she says, “those seeking antique lands were forced to acknowledge the colonial encounter, as it was impossible to get outside these power relations.”

Viewers are coaxed to wonder how visual cliche may also be considered ritual. Stephens points to endless footage of waterfalls, to throngs of image-takers at the Taj Mahal, and redundancy in shots of the Ghats in the holy Indian city of Varanasi. (The latter, not-so-incidentally, is the site of anthropologist Robert Gardner’s controversial 1986 film Forest of Bliss, ever-on-trial as a work of Western parasitism.) Perhaps amidst tensions of being known or unknown, imagistic cliché is a cocktail that blends shared human interests — large bodies of water, for example — with learned rituals of belonging shaped, like everything else, by structures of power.

How to get outside of power? How to claim absence? A tangle of paradox courses through Terra Femme, which proffers no authority. At its heart is a radical gesture towards unnaming, a pulsing reverence for that which remains out-of-step with classification, hot takes, singular heroes, celebrities and auteurs of mythical proportions. “Decorated are the names of the prominent,” Stephens narrates, “but it’s the nameless who weave the world into being.” The film’s impact is decidedly not that of a lecture or documentary, but of an artwork that is both complete and infinitely permeable, a softly radiant tracing of that which belongs to a void.

All stills from Terra Femme courtesy of the artist.