There is a wonderful museum of the Bible on the fourth floor of the Museum of the Bible. Here, in a large, attractive gallery are displayed hundreds of Bibles and Bible fragments — single leaves, scrolls, and codices from many different centuries and regions, in almost a dozen languages, on papyrus, parchment, and paper, the majority of which were painstakingly written by hand. This is just a small part of the vast — and controversial — Green family collection, which in less than a decade of aggressive (and according to some critics ethically dubious) acquisitions has swelled to tens of thousands of Bible-related items. (Although the Museum website insists that it follows ethical collecting practices, there has been much criticism of the Green family’s approach to acquiring, importing, and handling biblical artifacts. See Candida R. Moss and Joel S. Baden’s 2017 Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby from Princeton University Press.) Some visitors may feel uncomfortable at the idea of sanctioning a collection assembled through questionable methods. But no one interested in the Bible, book history, or religious history can fail to be thrilled by the artifacts assembled here. To give some idea of the range, artistic quality, historical importance, and sheer human interest of the collection, let me single out just a few objects.

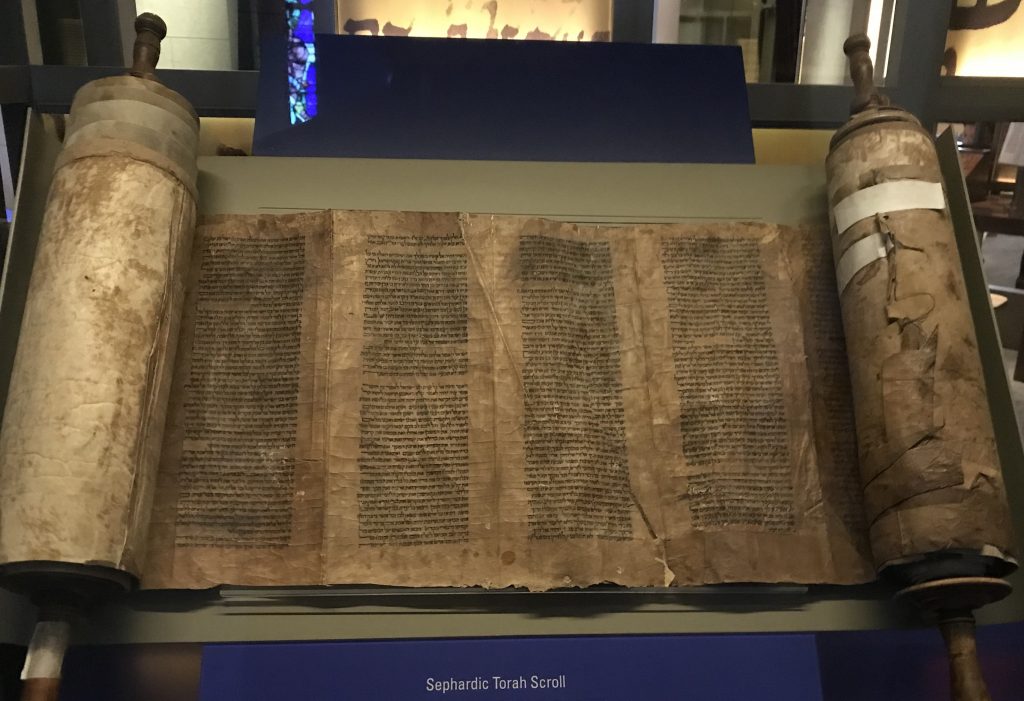

The entire story of a people seems encapsulated in a handsome, if somewhat ragged, Torah scroll made primarily in Iberia in the 13th century, but with membranes added in Poland in the 19th century.

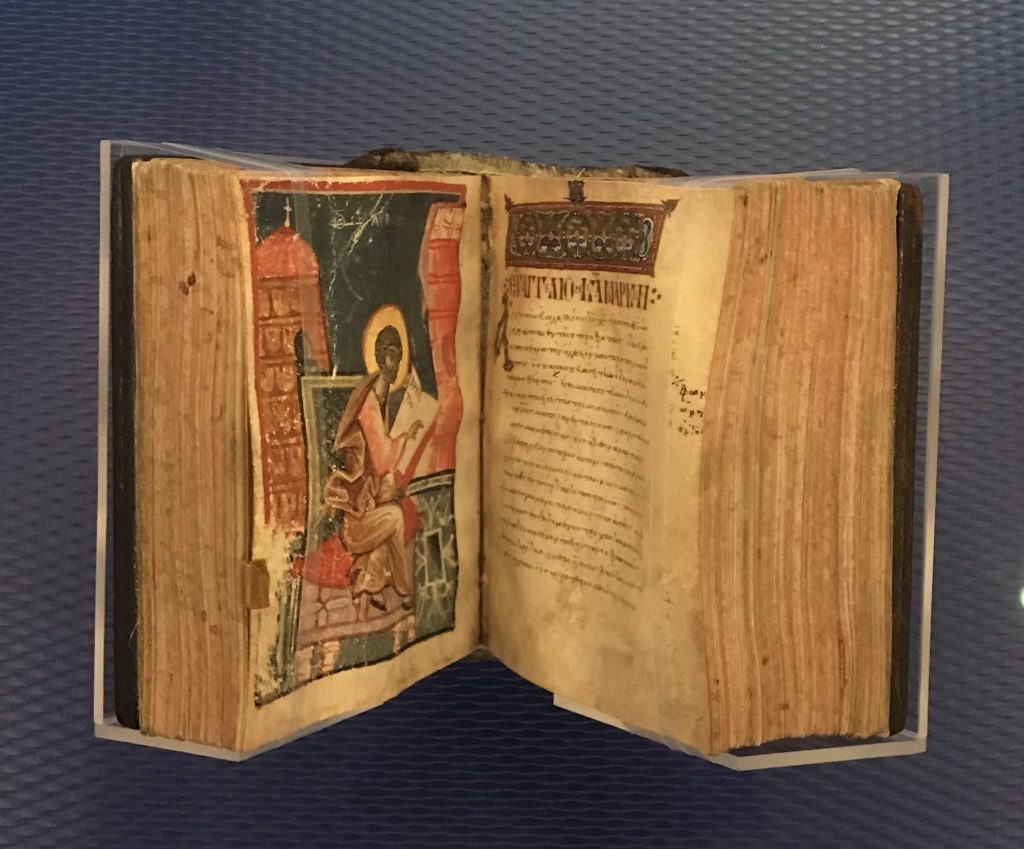

An 11th-century Byzantine Gospel with colorful illuminations added at some point in the 14th century gives us an intriguing glimpse into what treasured possessions manuscripts were, and also how tastes changed over the centuries.

There are several stunningly lovely illuminated medieval Latin prayer books whose decorations glitter with gold leaf, including a lavish prayer book made for the noble grandmother of King Henry V, and a scarcely less elegant psalter owned by a middle-class married couple from 15th-century London.

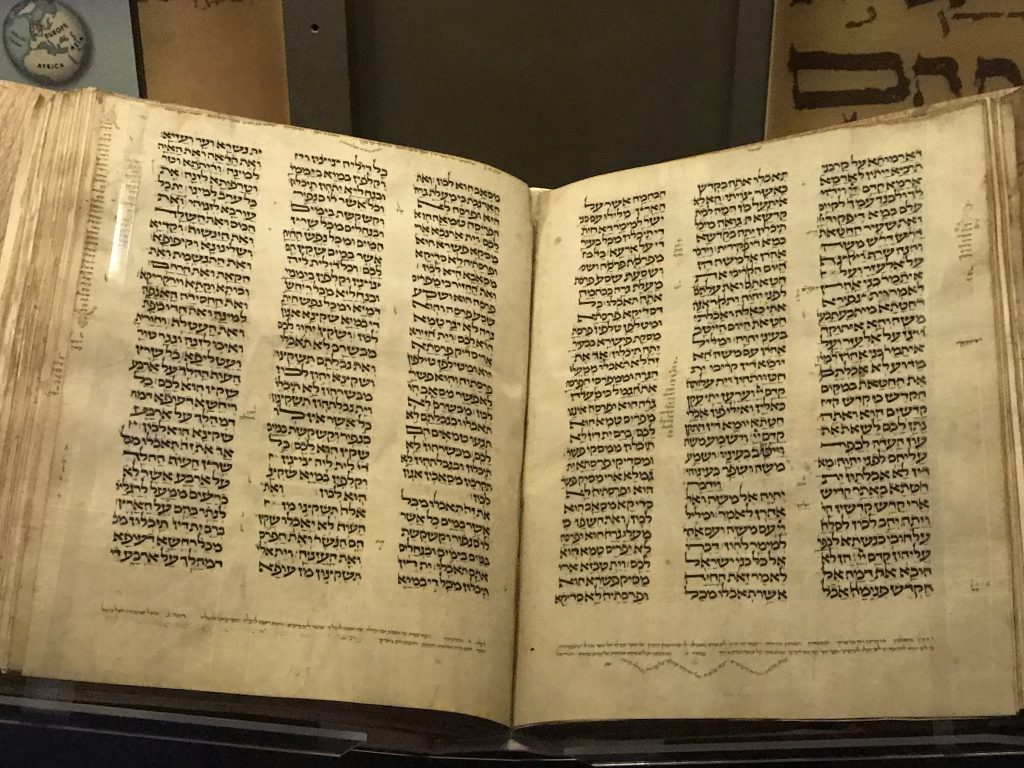

Though it boasts neither color nor precious metals, the Valmadonna Codex, a Hebrew Bible made in England in 1189, is a major treasure — the sole surviving example of a Hebrew manuscript made in medieval England.

On the other side of the spectrum, three plain, palm-sized Paris “Pocket” Bibles — the 13th-century equivalent of the cheap, portable modern paperback — remind us that the Bible was a text used for study as well as prayer and display.

Unfortunately, the interpretive texts rarely do justice to objects they explicate. While the labels provide the necessary basic information about the codex or scroll, they tend not to identify the folio or segment on display, leaving the visitor to guess at the meaning of the words or image before them. Moreover, they often leave out the most interesting or edifying information. For example, the text panel for the Valmadonna Codex notes that it is “the only clearly dated Hebrew manuscript copied in England before the [1290] expulsion,” but it doesn’t say how the codex was determined to be English. This is, in fact, a fascinating story. Until 1985 scholars assumed that the codex was made on the continent, since it was believed that no Hebrew books were produced in medieval England. But in a study published that year, the director of the Jewish National Library pointed out that the marginal notes to Leviticus 11 translate the names of the birds mentioned into Anglo-Norman, the dialect of French spoken in England.[1] These French glosses appear on the very page being displayed, though the non-expert has no way of knowing this. Referring, even briefly, to these discoveries would have allowed visitors to better understand what they were seeing, and learn more about the culture and interests of medieval English Jews.

The “Bible” presented in this gallery is distinctly that of the so-called “Judeo-Christian tradition” — although the Qur’an was strongly influenced by and shows many affinities with the Hebrew and Christian scriptures, it does not appear here as a biblically-related text. Nevertheless, within the confines of that definition, the exhibit is admirably wide-reaching. Rather than promoting a narrow, Protestant evangelical version of Bible history (as was feared by the Green family’s critics), it acknowledges the text’s centrality to Jews, Samaritans, and a wide range of Christian denominations — Orthodox, Syriac, Catholic, Coptic, Armenian, and others. Overall, the objects assembled here vividly demonstrate the variety of people, cultures, and periods that read and cherished the Bible, the great care that has been lavished on its physical embodiment, and the many different ways in which it has been used.

Next to the Green Family Bible collection is a gallery entitled “History of the Bible,” displaying a range of objects from cultures contemporary to the Bible, many on loan from the Israel Antiquities Authority. This exhibit is rich, fascinating, and valuable. It is also an exercise in evasion. The well-written and informative labels helpfully point out the many correspondences between ancient Near Eastern cultures and biblical stories and rites (one vitrine, for example, examines similarities between Mesopotamian law and Levitical law), but it never opines on the relationship between them. Visitors are left to guess why practices from so many different places and times appear in the Bible, presumably in order to avoid explicitly acknowledging that scholars see such correspondences as evidence for the gradual composition of the different biblical books by many generations and in various locations.

The rest of the Museum of the Bible fails to live up to even the mixed quality of these two displays, or to its name, being both rather short on actual Bibles and artifacts, and not particularly museum-like. Instead of objects and interpretation, the bulk of the massive display space is given over to various exhibits, projections, films, touch-screens, kiosks, games, and costumed actors designed to provide “an immersive and personalized experience…using cutting-edge technology to bring the Bible to life.” These range from interesting and informative to fun, odd, problematic, tedious, and downright offensive.

The second floor, dedicated to exploring “The Impact of the Bible” in different geographical regions and media, opens soberly enough, with a long, narrow gallery entitled “The Bible in America.” Through the display of a small but fine selection of Bibles brought to or printed in the Americas, supplemented by a large number of reproduced and enlarged photographs and prints and extensive explanatory texts, this section offers a thoroughly researched overview of the kinds of Bibles made and used in the Americas, the different American communities that used the Bible, and various historical movements, crises, and controversies in which the Bible figured. As with the Bible collection exhibit, there is less overt evangelical propagandizing than one might have feared. Darker aspects of American religious history do appear: the intolerance of the Puritans and the role of the Bible in justifying as well as fighting slavery are acknowledged, for example. But this is, nevertheless, a very selective history, with a distinct polemical message: the U.S. is a Bible-based society. We meet English, Dutch and African American Protestants; Jews; Native American converts; and French and Spanish Catholics, but little mention is made of the presence in the Americas of Muslims, Hindus, adherents of surviving indigenous religions, or atheists. It is also, somewhat surprisingly (given the fact that this is presumably the section of greatest interest to the Green family), not a particularly engaging exhibit. The space is rather cramped, the lighting is dark, and the story is told overwhelmingly through long text panels which even I — a history nerd — rarely had the patience to read all the way through.

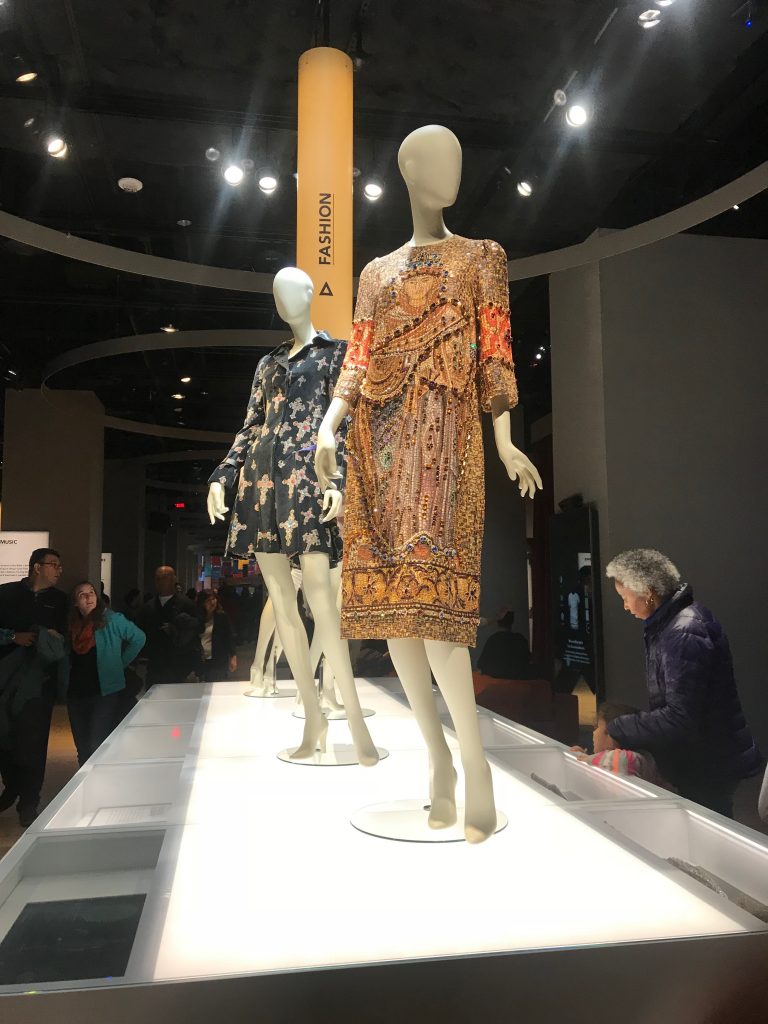

The next section on this floor, “The Bible in the World,” takes a very different approach. There is no chronology or narrative, and precious little in the way of information. Instead, visitors wander through somewhat randomly scattered island-like displays on such (overwhelmingly celebratory) topics as justice, human rights, compassion, health, and natural philosophy. None treat their subject in any depth. A display on “Martyrs for the Faith” is too superficial for such a serious and complex topic, consisting of a pile of burned books, a panel that summarizes 1,500 years of religious disputes and persecutions in eight sentences, and a projection that rapidly scrolls through images of early Christian, medieval, and early modern martyrs. A corner on “The Bible in Literature” features book covers mounted on a white wall, and a panel listing biblically-influenced Shakespearean passages. A row of mannequins wearing haute couture creations by Alexander McQueen, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Gianni Versace adds considerable glamor, but their connection to the Bible is tenuous at best, one dress being loosely inspired by Catholic priestly vestments, and another by a Byzantine mosaic of the Empress Theodosia.

A small corner on “The Bible in Art” contains some lovely artworks, though the system underlying their selection and display is unclear. A 16th-century painting by Francesco Granacci of the Madonna and Child with John the Baptist on the Flight to Egypt (which, as the label notes, is a non-biblical scene) hangs near an African-inspired 1995 painting of a calm but grieving Mary by David G. Wilson, defiantly titled Madonna of the Nappy-Head Christ. A full-sized, working reproduction of the Gutenberg press, operated by a printer in 15th-century dress, is both engaging and educational. But I was frankly appalled by a kiosk in the shape of a jail entitled “Identity Transformation and the Bible,” featuring photos of and religious testimonies from inmates in the Angola Prison Bible College — all men, mostly of color. That some people’s lives can be changed by the Bible is indisputable. But to so blatantly endorse the missionizing of a literally captive population, and to imply that crime can be pinned on a putative previous lack of faith, is, in my view, deeply objectionable.

The second floor is completed by two truly immersive exhibits — a room-sized colored screen conveying “The Bible in Data,” whose proportions and brightness seem designed to put CNN’s election-night graphics to shame, and an indoor roller coaster dubbed “Washington Revelations,” which sweeps its riders past a map of Washington D.C. as biblical inscriptions on building facades light up. These were clearly (and, judging from the squeals of the children, successfully) designed to amuse rather than to educate, though they too promote an idea — that the Bible plays a central role in modern politics and society.

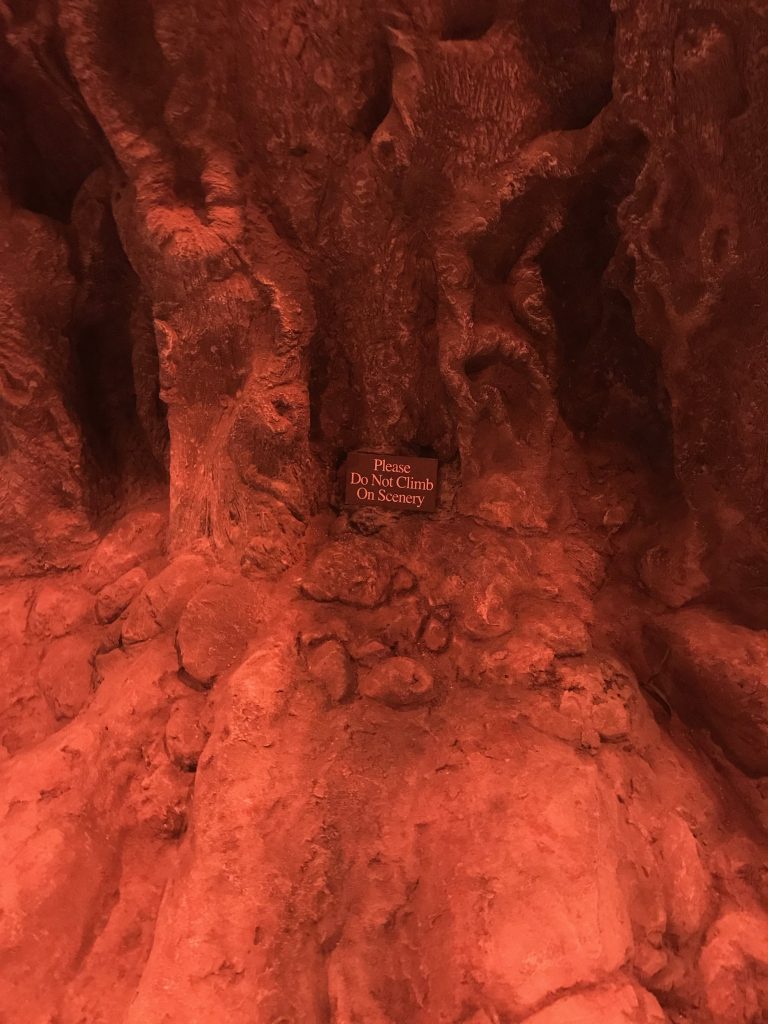

The theme-park feel continues on the third floor, dedicated to “The Story of the Bible.” The “Hebrew Bible Experience” was closed the day of my visit, but it apparently consists of a tunnel whose walls are lined with dozens of smalls screens projecting stories from Genesis, Exodus, and the like. “The World of Jesus of Nazareth,” imagines Jesus’s home town (which is not described in any detail in the Gospels) as a dusty Galilean village, complete with (sheet rock) faux-stone huts, olive trees, carts, courtyards. A rather grand, columned “Pharisee’s House,” in which a bearded, robed, sandal-wearing actor playing the role of host explains Jewish customs to curious visitors, is presumably intended to provide some cultural context. But there is no systematic overview of history, politics, or society in first-century Roman Judea, or of how Jesus’s ideas grew out of, or related to, his world. The families seemed to be enjoying themselves immensely, however.

The final stop on the third floor, “The New Testament Theater,” is likewise is not a place to learn more about the composition or contents of the New Testament. Instead, it offers a 12-minute-long child-friendly animated film offering a much-watered-down digest of the Passion story, narrated in the first person by a now-elderly Apostle John. The film never acknowledges the fact that the different Gospels present somewhat different versions of the event, and so obscures the complexity of the early Jesus community and of the textual tradition. Historical anachronisms abound — Paul makes an appearance, though he played no role in the Passion story and never appears in any of the Gospels, and he kneels to pray, though first-century Jews did not kneel in prayer. Here, more than anywhere else in the museum, a distinct missionizing flavor comes through — the film closes with a verse from I Corinthians 13:13: “But now faith, hope, and love remain.”

¤

I have no theoretical objection to the interpretive position taken by, or non-traditional aspects of, the Museum of the Bible. A private institution undoubtedly has the right to forward its constitutionally-protected religious beliefs. Similarly, there is nothing wrong with trying to make a museum visit a fun and lively experience. The current generation is undoubtedly more comfortable with new media, and impatient with static text. Most of the visitors I saw regarded the interactive bells and whistles with pleasure; the many children zipping around the large space seemed to be having a very good time.

But it is, nonetheless, distinctly ironic that a museum devoted to the Good Book, whose founders espouse a creed of sola scriptura (Scripture alone), seems so reluctant to state its attitude toward that scripture more openly, and also is apparently very insecure about the ability of that book to hold its visitors’ attention. Rather than plainly laying out evangelical ideas, the exhibits construct an unstated argument through omission and suggestion. Rather than using new technology to illuminate the development, structure, ideas, and shape of the Bible, the exhibits flatten and simplify its complex contents, history, and impact. As a result, most visitors will remain unaware of the extent to which they are getting a selective view of the Bible, and ignorant of much of what is most fascinating about what is undoubtedly one of the most influential texts in history. How and why that text came to influence so many, is a story that remains untold by the Museum of Bible.