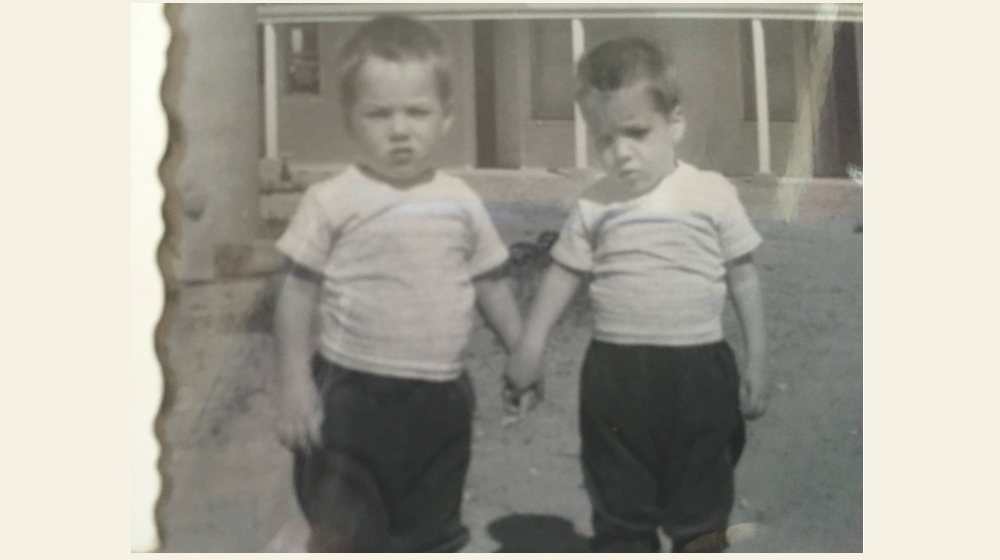

I’m an identical twin, born under the sign of Gemini. When my brother Kerry and I were children, my mother would call to us, “Twins — come here,” as if we were indistinguishable from one another. If our mom couldn’t tell us apart, who could?

In school we switched classes — he did no better in my algebra class than I did and I made little progress sanding his wooden duck in shop class. But the teachers didn’t notice and our close friends snickered along with us in the back of the room. I took one for the team when I gave my brother my license when he got into a car accident — I was in the back seat and he didn’t have his. For Halloween we once dressed up as “twins” — how meta is that — and two entries for one ticket at the movie theater was easy to pull off.

There is something celebratory and powerful about this kind of trickery, the ability to “get away with it” right in front of the people responsible for the tracking and surveillance that makes society function. The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips thinks that getting away with something is an assertion of freedom but also a kind of transgression. Higher authority is weakened and exposed, Phillips believes, its capacity for oversight and omnipotence undermined. How can you reward or punish the right person if you can’t tell who is who?

A fascinating and troubling documentary film about triplets separated at birth is currently in theaters. Three Identical Strangers tells the story of three brothers (Bobby, David, and Eddy) given up at birth to an adoption agency in New York that then delivered the triplets to three separate families: one working class, another middle class, and the third more wealthy. None of the families was told that the baby they were receiving had two identical brothers.

It was in the service of “science” that this ethically dubious practice was rationalized. It turns out that a psychiatrist Peter Neubauer was conducting a “nature v. nurture” study and the separated triplets provided the perfect experimental setting. By studying the progress of the brothers raised in different environments, important data about the relative contributions of heredity and the environment to personality development, individual traits and the course of their lives could be quantified.

Lawrence Wright, a journalist who wrote about Neubauer’s experiment in a series of articles in the late 1990s for the New Yorker, observed that behavioral genetics — of which twin studies were a foundation — had crucial political implications by impacting the debate about what government should do to help its citizens. If twin studies proved that regardless of the environment or access to societies resources the intelligence and life success of individuals would remain the same, then why “waste” money and time trying to improve the life prospects of people who would not take advantage of those expenditures?

Historically, the supposed implications of twin studies have been used to justify class stratification in Britain, colonial domination of “backward” societies, and the gutting of the social safety net in the United States. “Twins have been used to prove a point,” Wright wrote, “…and the point is that we don’t become. We are.”

While watching the documentary I was reminded of my own upbringing — not the separation but the intense interest from the “scientific community,” about what was going on with my brother and me.

I vaguely remember participating in a Minnesota “twins study” — one of the largest of its kind — that required I.Q. tests, personality inventories, and responding to abstract “Rorschach” ink blots that supposedly measured underlying emotional or cognitive states. One of the tests — which I still have — asked whether I believed in law enforcement, or if I ever felt like I was being followed, questions which I must have answered “yes” and “no” to in 1965 but would answer differently today.

It’s not clear exactly what the researchers were after or what quandary they were interested in, but it is pretty clear to me that my brother and I, as close as we were, had developed quite distinct personalities by the time we were adolescents. Being seen as “one” entity can be a great impetus towards psychological differentiation.

The documentary also portrays three boys struggling to form an identity, sometimes a singular one. An aunt interviewed in the film says that once they were re-united “They belonged to each other. They knew each other. Three lives became one.” One of the twins — I lost track of who was who during the course of the film — recalls that they “wanted to be alike.”

The media gobbled it up of course. On the Phil Donahue show they crossed their legs at the same time, told the audience that they liked the same type of women and smoked the same cigarettes — performing their twinship according to expectations.

Mark Twain, who was fascinated with twins, fragmented identities and impostors, had a keen understanding of how twins and doubles were grist for satire but also potentially threatened the social order. His story Those Extraordinary Twins, is based on conjoined twins (he referred to them as “freaks”) who were “on exhibition” touring the United States. Twain says he subsequently “took those twins (Luigi and Angelo) apart and made two separate men of them” for the novel Pudd’nhead Wilson. The plot contains indistinguishable “white” and “black” babies switched at birth, twins accused of murder, a critique of slavery and the slippery nature of the legal system.

In the earlier twins story, Luigi and Angelo go on trial for assault and battery. The jury acquits both, as they cannot determine which of the conjoined twins committed the assault. While they conclude that an assault actually did take place, the jury’s logic is that, “We cannot convict both, for only one is guilty. We cannot acquit both, for only one is innocent. Our verdict is that justice has been defeated by the dispensation of God, and ask to be discharged from further duty.”

The judge, aghast at the jury’s verdict, chastises them for setting adrift and unpunished, “… two men endowed with an awful and mysterious gift, a hidden and grisly power for evil — a power by which each in his turn may commit crime after crime of the most heinous character, and no man be able to tell which is the guilty or which the innocent party…”

The “mysterious gift” is how twins or imposters might escape the reach of the law and the certainties of identity, challenging the strictures of what anthropologist James C. Scott calls the “administrative ordering” of society. The untrackable and unidentifiable scofflaws or potential rebels, free from conscription and taxes, are always a “thorn in the side of states,” Scott writes in his book Seeing Like a State.

The psychiatrists and adoption agency who separated the three brothers at birth almost got away with it as well, until the adoptive parents started asking uncomfortable questions. The most damming one was “How could educated and ‘enlightened’ scientists justify not telling the parents that the boy they were receiving had two brothers living in the vicinity?”

The triplets thrived for a period, partying hard in New York, starting a restaurant — called Triplets of course — marrying and beginning their own families. Eventually there is a falling out about who is working harder at the restaurant, and Eddy — for reasons that the film perhaps necessarily leaves obscure — commits suicide.

The documentary takes a cheap shot at Eddy’s father by having a relative suggest that he was stricter and more emotionally distant than the parents of the other two. This comes down comfortably on the side of nurture in the nature/nurture debate, letting the audience off the hook. After all, if one of the triplets killed himself and his other genetic clones didn’t, there must be a culprit.

If the similarities of twins separated at birth are “unsettling,” challenging assumptions about our own uniqueness, then pinning a suicide on bad parents at least allows us the conceit of believing we have the freedom to create ourselves anew by constructing or escaping to a different environment. It is the living in this case who survive to interpret the death, providing the contingencies of life and its end a plausible meaning.

In Three Identical Strangers, like in all tragedies, nobody gets away with anything. Neubauer and his fellow experimenters are condemned for their immoral actions. The two surviving brothers cannot re-create the utopian solidarity of their initial reunification. And there is no definitive answer to the precise impact of the environment or genetics in determining our personalities and our fate. Lawrence Wright only concludes that “Genes and the environment are close competitors.”

What remains is guilt. The two surviving brothers lament that they could not save Eddy. A surviving member of the original experimental team sheepishly explains that the rules on separating children were different “back then.” At a film screening during the roll out of the documentary, someone approached the two brothers and apologized “on behalf of all the research psychologists in the world.”

Guilt, as the psychoanalyst Phillips tells us, “…is our word for not getting away with it.”