A show of staggering importance is now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor (through March 17, 2019) is to date the largest museum retrospective dedicated to a painter born into American slavery, featuring 155 works from 57 lenders. Traylor, born in 1853 in Alabama, taught himself how to paint in his mideighties, leaving behind more than 1,000 paintings at the time of his death at the age of 96. “His existence,” Between Worlds curator Leslie Umberger writes, “was almost equally divided between two centuries.”

Tall tales have been told about Traylor’s life, and his oeuvre mischaracterized ever since he first exhibited publicly in the 1940s. Moreover, an underrepresentation in public art collections limited access to his work. But under the careful curatorial eye of Umberger, who worked on the exhibition for seven years, myths about Traylor’s life and artwork have been dispelled, and new interpretations are allowed to surface, in part because of the wide range of works on loan. With the catalog and the exhibition, Umberger emerges as the finest interpreter of Traylor’s life and career, proving she is an American curator and art historian of the first order. And, at long last, Bill Traylor’s artwork takes center stage to speak to viewers of the pasts of the present, in an exhibition that provides access and understanding.

The blood-soaked history of Alabama and the Deep South is inextricably braided with Traylor’s biography. In early spring 1865, with the Confederacy in its death throes, the Union cavalry set out to destroy rebel manufacturing facilities and plantations near where a preteen Bill Traylor was enslaved. Traylor, suspended between his slave past and an unknowable future, hid in a hollowed-out tree trunk as Brigadier General James H. Wilson’s Union Army Calvary Corps caused mayhem along the Alabama River. When he emerged from the woods, Traylor found the plantation where he was enslaved scorched and the farm animals slaughtered. Though just a young boy — not yet an artist but possessing an indomitable spirit — he was about to become a free man.

For the next five decades, Traylor worked as a laborer and a farmer on or near the Lowndes County lands where he and his family were once enslaved. We have little evidence, excepting census records, of this time of Traylor’s life, up until 1938. At this point he was in his eighties and homeless, drawing on discarded cardboard in the center of Montgomery, in the Monroe Street Black Business District, one of the most vibrant black neighborhoods in the country. In possession of, first, a pencil, and then a brush, Traylor refined his hand with constant practice.

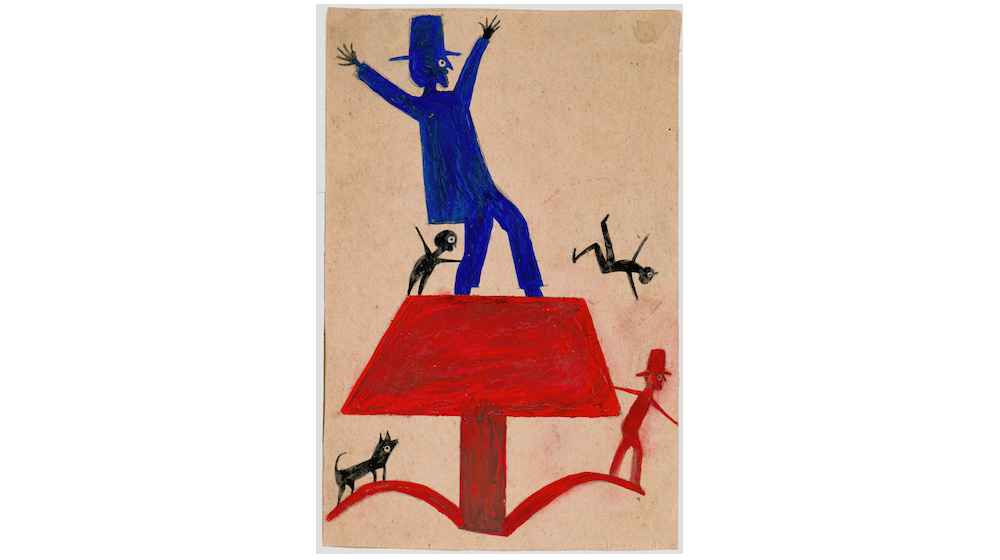

Traylor’s paintings from this relatively short working period are populated with figures and animals portrayed in profile or as abstracted silhouettes, in slightly surreal domestic compositions or extracted from figure-ground context. In either case, Traylor is a storyteller par excellence, troubling expectations and creating narrative mystery. There are carousers, crucifixes, ring shouts, and enigmas we can only guess at interpreting. Some of Traylor’s characters, especially the ones seen drinking and dancing, seem ready for any and every mischief; high drama characterizes his representations of animals, often fighting and chasing one another. Traylor organized many of these paintings vertically, animating kinetic (and sometimes frantic) compositions. He worked with a limited palette, perhaps out of means and necessity, but these colors may also refer to scenery where he was raised: in the springtime of still-rural Lowndes County, the wisteria blooms a phosphorescent yellow, the phlox an electric blue, precisely the colors Traylor chose for his work.

Matisse’s cutouts make for an apt comparison in style, if not in subject. Both artists developed a singular reduction of form in their last decade of life, which roughly coincided in the 1940s. I am tempted to venture that for Matisse, making art into his mideighties, and for Traylor, into his midnineties, working in the dying light of advanced life inspired a development of style that invokes pure and direct emotions. As the Japanese artist Hokusai said in his midseventies about the art that he planned on making into his centenarian years, “All that I do, every point and every line, shall be instinct with life.” Traylor’s art is refined to an essence.

The exhibition strives to show the full creative expression of Traylor’s inner self; in the catalog, Umberger writes about bringing “together long-separated artworks that are related in content” to “give in-depth attention to Traylor’s imagery, narratives, and symbolism.” The special exhibitions galleries are divided into 16 sections organized thematically; besides Traylor’s work, the walls are, for the most part, blessedly unfettered by exegetic wall labels. Visitors are encouraged to directly engage the obscure scenes and enduring carnivals of action to find their own matrices of meaning. I found perfect strangers, young and old, talking to one another about Traylor’s intent. Traylor’s narrative ambiguity and elemental forms inspire such conversation, and are part of the reason why he remains such a fascinating American artist.

While visitors will be moved by any number of paintings, the artworks organized under “Chase Scenes” and “Mortal Peril” are of considerable consequence. Umberger’s selections unequivocally illustrate Traylor’s reflections on the violent Jim Crow South, portrayed metaphorically or symbolically. Here the lynching tree is a leitmotif, or the eloquent depiction of the precise moment a rabbit springs to escape harm can take on another meaning. Umberger writes, “It is in these works that Traylor’s skill at creating double story lines and ambiguity to obscure or reveal different meanings — one for black viewers and another for whites — [is] the most evident; what seems a possum hunt to some is a sinister pursuit to others.” Her claim is that only the most careful of observers would have recognized what he was doing; with this subversion “Traylor would not live to see the civil rights movement, but he was among those who laid its foundation.”

Black artists have drawn upon African-American oral traditions and folkways for many generations, but rarely is it given such preeminent stature and critical attention in the context of a national art museum. This exhibition makes the argument that Traylor’s deep knowledge of African-American folklore made an indelible contribution to the narratives in his paintings. Moreover, in keeping with the broad interpretation and appeal of Traylor’s work, Umberger invited musicians, folklorists, artists, and a descendant of Traylor’s to contribute their interpretations to the website for SAAM. Folklorist Bill Ferris examined “Exciting Event with Snake, Plow, Figures Chasing Rabbit” for Between Worlds:

We could think of this work as a story, a part of black oral tradition, rendered with visual images. And within those images are embedded the great symbols of black experience in the South: the mule, the symbol of endurance and survival; the snake, the chief god Damballa in Vodou; and last but not least, the chase of the dog and the rabbit, and the people following evokes the history of slaves trying to escape their brutal lives. The idea of being pursued, as a black person by whites, is a long and deep story. And finally, the rabbit is a familiar figure in black folktales. The rabbit is the most important trickster figure in African American folklore. The trickster is a small, physically weak character who outwits and prevails over larger adversaries, the rabbit outwitting the fox and the bear. So, Mr. Traylor has embedded in this single piece, really, the history of his people in the South for over two centuries.

In previous exhibitions, Traylor and his artwork were often qualified as “primitive,” “outsider,” or, more recently but no less problematic, “outlier.” In 1946, one of the first journalists to write an article about Traylor stated, “Through some capricious blunder of the centuries, this old plantation Negro is painting like the prehistoric cave artists.” In the 1980s, when Traylor’s work was included in the famous exhibition Black Folk Art in America, his art was described as possessing a “Paleolithic élan.” As recently as October, reviews in The Washington Post and The New Yorker reference prehistoric cave paintings to describe Traylor’s art. These recent descriptions continue a legacy of pejorative mischaracterizations; such language fetishizes the artist, does not attend to the particulars of his life, and offers nothing by way of critical analysis of the artworks. A far better description is that of art historian Lisa Farrington, who writes that Traylor’s work “is essentially Modernist in the unmodulated flatness of his forms and palette and in his lack of interest in anatomical exactitude.”

As the peerless, Alabama-born artist Kerry James Marshall writes in the introduction to the Between Worlds catalog, “Traylor and his work have come to embody many of the complexities and contradictions argued around aesthetic hierarchies and the issue of insiders versus outsiders in the construction of art history.” Marshall argues that “no such distinctions should prevail, especially since the work of some formerly marginalized self-taught artists can seem more appealing in spirit if not technical sophistication than artworks made by academically trained artists.” Amen. Between Worlds is a testament to the enduring, inclusive genius of Bill Traylor, a man who came from slavery to make a world all his own. Traylor’s paintings remind us of the indomitable creative spirit, enduring beyond this nation’s sins.