On January 20th, America inaugurated a new president. He is a plutocrat who made a mint plastering his name on buildings and shellacking everything in gold like some sort of cut-rate Midas. He is a creature of the media — a whore for attention and a brazen liar. It was theoretically amusing, in years past, when he was simply taking turns on reality TV and pretending to gossip columnists that he was his own PR agent. During the early days of the campaign, the nation was all too content to suffer this particular fool so long as he kept the campaign interesting. Never forget CBS chairman Les Moonves’ words that Trump’s campaign “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” When we all started living in his personal reality TV show — when he won — he became terrifying.

Anyone who watched his January 11th press conference could easily discern that he is a danger to the Fourth Estate. He attacked the press — which was gathered there explicitly and only for him — calling it unprofessional, fake, and full of liars. His evidence for this was that they reported things he didn’t like; namely, that national intelligence agencies are circulating a summary of unconfirmed research claiming that he’s a stooge for Russian spies and a potential blackmail target for none other than Vladimir Putin.

The press is only just now beginning to realize how tenuous their position is, just as the #NeverTrump Republicans and then the Democrats only started to realize how dangerous Trump could be when it is already too late. He uses childish antics and seeming ignorance as cover for extreme cunning. On the one hand, Trump has embraced Peter Thiel who funded slow-burn lawsuits against Gawker in retaliation for unflattering coverage and eventually succeeded in bankrupting the company.

On the other hand, Esquire reported on January 14th that the incoming Trump team wanted to close the White House press room, something which has existed in one form or another since the Teddy Roosevelt administration. The excuse given publicly was that they needed to accommodate more media outlets than the current space can effectively serve. But an anonymous insider told Esquire’s Peter Boyer that the real reason is that Trump and his stooges see the press as “the opposition party.” The insider continued: “I want ‘em out of the building. We are taking back the press room.” In other words: Make The Media Great Again.

Even if we take the public reasoning at face value, that there is not enough room in the current briefing room, it does not bode well. Russian investigative journalist Alexey Kovalev recently wrote an advice column of sorts to the American media, based on his experience covering Putin. One of his warnings: “It’s in this man’s best interests to pit you against each other, fighting over artificial scarcities like room space, mic time or, of course, his attention…Also, some people in the room aren’t really there to ask questions. Expect a lot of sycophancy and soft balls from your ‘colleagues’…There will be people from publications that exist for no other reason than heaping fawning praise on him and attacking his enemies.”

Imagine, then, that the White House press corps has been relocated to some dilapidated office building and the 30-odd real journalists there are then surrounded by several hundred pro-Trump bloggers and the entire Breitbart team. (On the 18th, the Trump team sort of backed off of the move. Sean Spicer, Trump’s press secretary, said that the press corps would “initially” remain in the White House briefing room, but left ample room for a subsequent move. And as a cherry on top, Trump implied that his team would get to pick which reporters get into the briefing.)

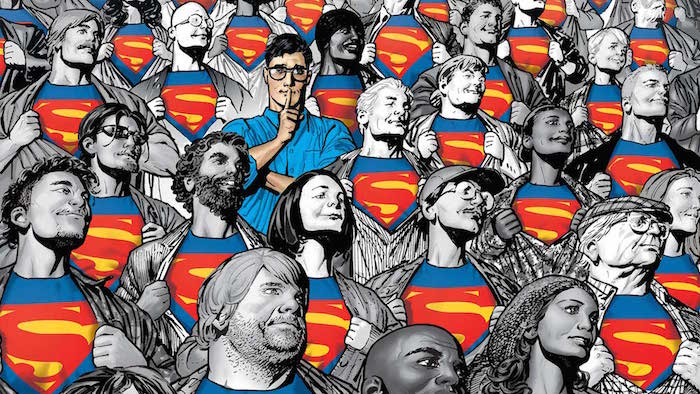

All of this leaves the Fourth Estate, and America in general, in need of a hero. Somewhat improbably, the perfect hero for our moment may be the nation’s oldest and squarest superhero: Superman. Back in October of 2016, before we knew Trump was going to be our next president, screenwriter Max Landis took on superhero in an anthology, Superman: American Alien that traces the hero’s life from the cornfields of Smallville, Kansas to Metropolis, the urban heartbeat of America.

The Superman that most people are familiar with is the flying man in a cape who bashes heads, works alongside the government, and whose authoritarian tendencies are only barely suppressed. Superman, traditionally, represents order and structure and a certain rural, white, working class sense of justice, which he metes out in the big city. He’s corn and potatoes and traditional morality. His alter-ego is mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. Kent never really does anything, though, and being a reporter functions more as cover for why he always winds up wherever Superman has just been in action. In other words, Superman can easily be seen as a Trumpian character. (True fans will complain that I am painting with a broad brush and ignoring the many times that Superman does not go along with the establishment; this is true to a point, but I am thinking specifically about Superman’s less-nuanced existence in the popular imagination.)

Landis turns this upside down. Despite the volume’s title, the main character is not Superman, but Clark Kent. Put differently, Superman is the alter-ego for Clark Kent, rather than the other way around. Growing up in Kansas, it’s clear he’s from another world; he’s weird, kind of a freak, and while his parents love him very much, he knows that Smallville limits him and that he is not really understood there (this doesn’t mean he is hated or even lacks friends; in fact, several of them visit Kent in the big city).

But Kent is an alien, first and foremost. He is the last survivor of the Krytonian race whose planet was destroyed 500 years before the events of the story. As such, despite looking much like those around him, Kent is different. He is, in the most extreme sense of the word, an immigrant to the United States. The story opens with Kent as a child, perhaps 12 or 13. He sneaks off to go to a movie with some friends from school, including his crush, Lana. The movie that night at the drive-in is E.T. the Extraterrestrial, and the kids sit on the grass. It’s a deliberately nostalgic scene. The reader joins the kids just as the government scientists, wearing hazmat suits, are entering the house to take away E.T. to perform research on him, and Elliott, the boy who has adopted the alien, is hooked up to diagnostic machines as he slowly dies. One of Kent’s friends chatters, “I don’t get it, how’d he do that?” To which Lana replies, “Shhhhh, he’s an alien — he has special alien powers, Kenny.”

The movie is making Kent visibly uncomfortable, and he squirms and whispers to Lana, “Do you really think they’d do that?” He’s clearly thinking about himself in E.T.’s place. In the movie, Elliott screams that the scientists are scaring E.T., and Kent has a panic attack. His latent powers send him soaring quickly into the air and then crashing to the ground. Well meaning, but confused, adults rush to him. “Is that the Kent boy?” “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Kent lashes out: “Leave me alone!” He hides in the bathroom, smashing the wall in anger. His father picks him up and they drive home in the family pickup, through the Kansas cornfields. “Dad… I’m so unhappy,” Kent confesses. “I want to be myself. I don’t want to worry that I’m something else. I’m scared — I just want to be normal. I’m not normal.”

His father gives him a hard look before replying: “Maybe that’s a good thing. You know what, yeah. That’s right. Who needs normal?” Kent is apart, separated and othered from his adopted community, no matter how hard he tries to be a part of it. His emotional experience can easily be interpreted as that of an immigrant (or a gay child, or a Muslim, or any number of other groups) living in a small, white, well-meaning but conservative town in the Midwest.

But Landis’ Clark Kent is not only an immigrant. He fully inhabits the role of journalist. He leaves his small town and moves to the big city – Metropolis, as usual, stands in for New York — and throws himself into the job of crusading reporter just as thousands of other young and idealistic people have in real life. Kent, while an intern for the Daily Planet newspaper, gets his big break thanks to some good luck and mistaken identity, and scores a one-on-one interview with Lex Luthor, a billionaire businessman who lives in a tower and aspires to run the world. While volume one of American Alien doesn’t get there yet, the cannon history of Luthor has him eventually becoming President, partly thanks to massive and corrupt real estate deals that he carries out in Gotham City. Luthor, when he meets Kent-the-intern, gives him a monologue for his article:

“There’s a fatalism that’s been going around, and I think it’s toxic — self fulfilling. I think fatalism is hip and pragmatism has gotten boring. I think dark futures are paradoxically easier to see than bright ones. Everyone talks about the problems of tomorrow, the apocalypse of next week, but whatever happened to the man of tomorrow? Why are we so convinced there aren’t those among us who could maybe solve these problems that seem so insurmountable to the pseudo-intellectuals who pose them? We’re scared to even talk about a hopeful future because we’re terrified it won’t come to light. We’re in some kind of global cultural rut of focalism — that’s why people won’t talk about a big opportunity, sometimes — you ever do that?”

After a testy exchange, in which Luthor realizes Kent is just an intern, he continues:

“You want a quote? I’ll give you one. People aren’t important. Not as a whole. Everyone runs around like they’ve got a big s on their chest for “special,” but the actual gift of genius, of work ethic, of aspiration, is rarer than a white tiger. That’s why you see people throughout history rising above the masses. Those are the changers. Those are the doers. You are not important. You’re not. I am.”

It’s one-part Trump and one-part Thiel, or perhaps all Putin. Kent is both giddy that he got the story, and disturbed by what the story is. He becomes a hotshot reporter at the Daily Planet and starts fighting crime and saving the city in a cape in his free time. But his fundamental concern is with truth. He confronts Luthor after the billionaire has released a monster to terrorize the city, but realizes that he cannot defeat Luthor without proving to the world what he did and why. Truth and fact trump Superman’s power and he knows it. His girlfriend, Lois Lane, also a reporter, is chasing the Superman story. Kent breaks down at dinner, without telling her he is Superman. Kent questions what Superman’s narrative can actually be:

“What makes you think if we didn’t have this flying doofus zipping around we wouldn’t have any monsters, either? Lois, he’s a vigilante — you don’t know what he wants, what he’s doing. What are this guy’s actual goals? Where is the why? He doesn’t give interviews, and if he did, what would you want him to say? Who do you need this person to be? Who does this whole city need him to be? The whole concept is a mistake…is he supposed to just always be there to save everyone? I see these people, they get a flat tire and they look up in the sky. ‘Oh, where is he?’ Is that what he wants? To be relied on by everyone? Stupid. What’s my — What’s his endgame? What do you want him to be?”

Clark Kent is the hero the world needs when its leaders manipulate their image, control the levers of business and use the state for their own enrichment. Kent is physically powerful but self-doubting, more concerned with whether his justice will be recognized as true justice than whether or not he wins. He wants to know his purpose — though deep down he knows exactly what that purpose is, if he can commit to action. He is the avenging immigrant journalist with a heart of gold who will stand up for the little guy.

Lois’s reply is simple: that she just wants “to believe that there’s someone out there who doesn’t suck.”

Perhaps that’s what America needs to today.