When I was pregnant with my first child, many parents foisted an observation on me that smacked of schadenfreude: “Your life will change.” As if I didn’t know. I was in my 30s and had witnessed plenty of other people with children; realizing the amount of time and attention parenthood demanded was one reason I had waited. A particularly annoying subset of this observation was “Your priorities will change.” We generally use the word “priority” to mean “a thing that is regarded as more important than others; something that needs special attention” (Oxford English Dictionary). I was a scholar, already published in major academic journals, and eager to complete the book I was writing. My professional identity also qualified as “a thing that is regarded as more important than others.”

I believe that these people meant to tell me that I would suddenly see my ambitions and my work pale in comparison to the importance of my children and their welfare. This happened in many ways — I did not search nationwide for an academic job that would have required either me or my husband to live apart from our children much of the time. But I also lost none of my desire to be a teacher and a scholar. The “your priorities will change” statement suggests that after having a child a person — most often a woman — will devalue her former aspirations, and that as she integrates and assimilates new values, she will be transformed.

I did not change in this way.

When I was a reading or writing, I was still myself, a professor, my old identity. What happened is that I split in two.

¤

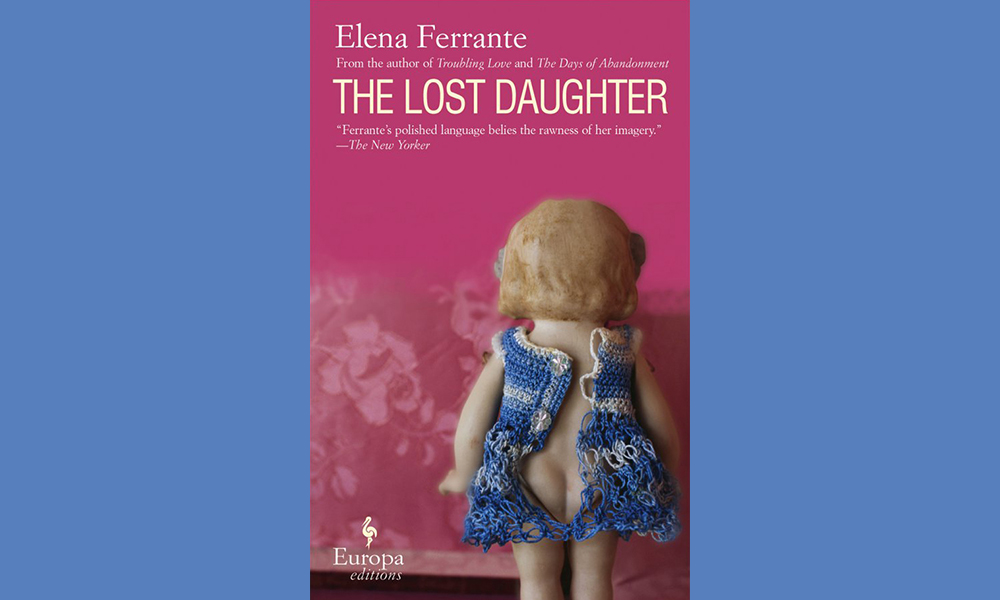

It is not surprising that I strongly identify with the main character of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter (2006, trans. 2008), a literature professor who was similarly divided — split — between love of her work and love of her two daughters. Leda had married another academic, and while his career forged ahead brilliantly, she was sequestered at home with two young children, trying to write in the interstices of childcare. At one point she attends a conference (her dissertation advisor gives her the money to attend) where her one published article receives abundant praise from a renowned scholar. She meets this man, and they begin an affair. Soon after, she decides to leave her husband and her children, ages four and six, cutting off all contact with her family for three years in order to pursue her career and her romance. Really, these two pursuits are the same. Her lover represents academia; her erotic fervor is as much a displacement as a passion. Leda literalizes the split in her identity, not reconciling her two selves (“your priorities will change”), but actually taking off into her other life and her other identity. Three years later, she returns and reassumes the care of her daughters.

Many societies, even today, encourage women to pursue careers but then fail to follow through with the support that would enable their success. And these are the problems women of relative privilege face; impoverished women have even greater difficulties simply providing food and housing for their children. In 2001, Anne Crittenden’s The Price of Motherhood detailed the ways that having children frequently curtailed the professional and financial potential of women. Conditions were sufficiently similar in 2010 to warrant an anniversary edition, and honestly, the same book would be appropriate today, only slightly revised and updated. In the United States, women still earn 81 cents for every dollar earned by men. Although in her bestseller Lean In, Cheryl Sandberg tells women to give their all to their careers and to assume they will be able to juggle work and family, leaning in means having the money and support to pursue success. An early-career academic like Leda did not have the wherewithal to buy the childcare and household help that would have enabled her to succeed.

When Leda returns from the conference where her article was so highly praised, she begins to take this time for herself, but her husband “protested that he couldn’t keep up with work and the children both.” Obviously, he does not regard Leda seriously enough to support her work, to sacrifice some of his success to ensure hers. Her best option in terms of her career is to leave, and then her husband is forced to cope. Not surprisingly, he finds a way to make having a career and children feasible for himself — a way he couldn’t find for his wife.

Like Leda, too many women feel anger and frustration at being thwarted in the quest to fulfill their potential, to develop what psychologist D. W. Winnicott calls the “true self.” Leda explains that she left her daughters because she “loved them too much and it seemed to me that love for them would keep me from becoming myself.” When basic needs are met, people turn to interests and ambitions for satisfaction; we are a species that does not live by bread alone. Nor is it the case that only contemporary women are frustrated in this way, although they often have greater ambitions than their foremothers. Leda recalls her own mother “screaming with rage… because of the crushing weight of responsibility, the bond that strangles.” Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, an analysis of the widespread depression that comes from such stunting, for that generation of women.

Narrating The Lost Daughter, Leda interweaves her account of the past with events that have taken place more recently during a solitary vacation by the seaside. Both are stories of the trials of motherhood. On Leda’s arrival at the beach, she encounters Nina, a gorgeous young woman who appears to be a perfect mother to her three-year-old daughter Elena: “If the young woman was pretty herself, in her motherhood there was something that distinguished her; she seemed to have no desire for anything but her child.” Nina seems to take motherhood in stride, to be a natural with no unsatisfied desires or conflicts. Leda envies this serenity.

Nina’s relationship with Elena revolves around their play with a doll which they both nurture. Mother and daughter attune to one another harmoniously, merging identities by taking turns making the baby talk, an aspect of the play that Leda finds particularly annoying. She becomes obsessed with this triad (Nina, Elena, and the doll), fascinated and exasperated at the same time. They represent a unity she failed to achieve, but one that also repels her; she was never a “motherwoman,” to use Kate Chopin’s wonderful phrase from the novella The Awakening. But Leda is envious nevertheless: how marvelous to be fully content with being a wife and mother, to be free of the nagging ambitions and longings that led her to take the drastic measure of cutting herself off from her children for several years. How different from Leda herself who, in her trials of self-discovery, left “damaged, lost things behind me.”

Leda’s jealousy leads to action. For a terrifying few minutes, Elena is missing on the beach, and Nina and her entire substantial clan (her husband’s extended family) search for her. Leda is the one who finds Elena, to the relief and gratitude of all. But the child remains inconsolable, for although she has been reunited with her mother, her doll is missing. Leda accepts the thanks of the family, but as she leaves the beach for her hotel her heart is racing: “I had taken the doll, she was in my purse.” Leda steals the doll to diminish its power as a symbol of reproach for her own failings as a mother. With a touch of magical realism, her attack succeeds. Once the doll disappears, the imperfections in Nina’s life, including those in her relationship to her daughter and to motherhood, begin to show. The child becomes inconsolable and ornery, driving Nina to express the kind of rage and discontent that Leda recounted in her own experience of motherhood. Nina confesses her distaste for her older husband, and Leda discovers her kissing a boy around her own age (23). “I just want to be a girl again,” she tells Leda. A girl — with a future ahead and free of the responsibilities of motherhood.

The doll is a fetish in Nina and Elena’s relationship. In anthropology, the fetish refers to an object that is worshipped for magical powers and indeed, the doll, and their maternal worship of it, creates harmony that vanishes with its absence. For Freud, the fetish is a substitute for the female genitals, an object eroticized to avoid confronting the castration anxiety evoked by the woman’s “missing” penis. To analogize Freud’s theory (without endorsing its misogynist suggestion) in this case, the fetishized doll creates a relationship that masks the true tensions of motherhood, which, like castration, is also a disempowering condition that is frightening to confront — most new mothers are overwhelmed to begin with. As with castration anxiety, maturation involves resolving this fear, but in both cases, the right conditions must lead to that resolution.

As they become closer, Nina asks Leda why she returned to her children:

“If you felt good, why did you go back”

I chose my words carefully.

“Because I realized I wasn’t capable of creating anything of my own that could truly equal them.”

She had a sudden contented smile.

“So you returned for love of your daughters.”

“No, I returned for the same reason I left: for love of myself.”

She again took offense.

“What do you mean?”

“That I felt more useless and desperate without them than with them.”

This is not quite the confession of having gotten priorities wrong that it might at first appear. Narrators are not always reliable — and Leda is not in this case. When she returns to her family, she has had three years in which to work and establish herself in academia. She became a professor of literature (she is grading papers and planning a course on her vacation), an achievement that was made possible by her having left her family. What she subsequently realizes is that her “true self” also consists of being a mother, of being there for her daughters. Leda does indeed return for love of herself, of the other part of her “true self” that she had split away from by leaving.

But here’s the crux: only after fulfilling her professional ambitions is Leda able to integrate the different parts of herself that had split apart. She says that after her return, “I was resigned to living very little for myself and a great deal for the two children: gradually I succeeded.” So, her priorities changed. And yes, her children were more important than her career. Nevertheless, her career was more important than many other aspects of her life. She could integrate the two parts of herself because both had been allowed to develop.

Leda does not have an easy relationship with her daughters. When they are teenagers, she writes them a letter explaining this period of her life, but they will not speak of the letter, and it seems likely they refused to read it. Nor do they speak of this time. Now in their 20s, they live in Canada, where their father has an academic post. Leda has paid a price for self-fulfillment. Women often do.

Even so, this is not an unhappy novel. Leda’s daughters know she loves them, and they love her in return. Whatever damage she inflicted, she also did much to repair it. At the end of her vacation, her daughters phone saying that they hadn’t heard from her in so long that they didn’t know if she was alive or dead. “Deeply moved, I murmured: ‘I’m dead but I’m fine.’” A rebirth, of a sort. Leda’s experiences with Nina, Elena, and the doll help her feel a sense of peace and resolution about the choices she has made. No mother is perfect, and women make compromises in the best of circumstances — conditions that few of us enjoy. But we adapt and we do the best we can, a best that is usually enough to make most of us, in Winnicott’s words, a “good enough mother.”