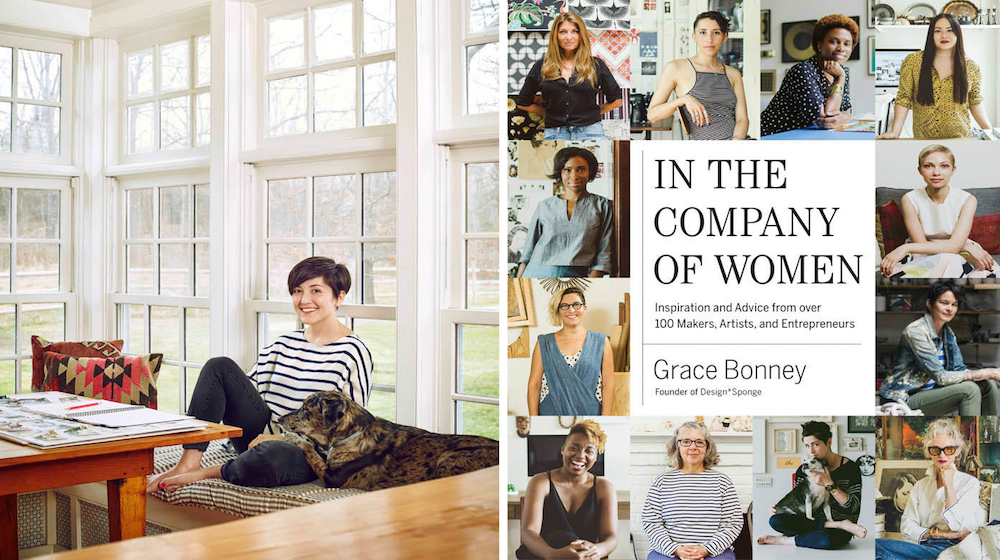

October 17th was National Boss’s Day — appropriate timing for Grace Bonney’s tour promoting her new book In the Company of Women: Inspiration and Advice from over 100 Makers, Artists, and Entrepreneurs. Bonney, of Design*Sponge fame, moderated a discussion panel that evening at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse, which was hosted by Book Soup and featured eight of the women she interviews in her book: author Roxane Gay, Native fashion designer icon Bethany Yellowtail, comedy writer Shadi Petosky, founder of TransTech Social Enterprises Angelica Ross, artist Tanya Aguiñiga of Aguiñiga Design, founder of Oh Joy graphic design studio Joy Cho, and co-founders of Block Shop Lily and Hopie Stockman. This diverse and multi-talented panel reinforced the purpose of Bonney’s book, which is “to provide motivating and relatable examples of all kinds of women running their own businesses, so that any woman, anywhere, can open to a page and see herself reflected.”

Discussion topics included ways to succeed and overcome self-doubt, how to find an effective “boss voice,” how to achieve a work-life balance and maintain self-care, and ways to deal with negative criticism and copycats in creative fields like art, fashion, and writing. The panelists admitted that these are things they still work on, and they opened up about the less glamorous sides of running businesses and being in the public eye, especially in the age of the internet.

In their introductory remarks, the Stockman sisters shared key lessons they learned during the first year of running their textile company, Block Shop. They outlined “the three crucibles of starting a small business” based on their mistakes: not having a mission statement; succumbing to the fear of their customers’ perception; and relying too heavily on online communication. Once they established their mission — which is to create socially responsible textiles with low environmental impact — business decisions flowed from there. They said they let go of the fear that their loyal customers would perceive them as “sellouts” for partnering with J. Crew, a deal that significantly helped their business expand so they could afford to hire more employees. And lastly, after receiving a botched shipment of textiles because they weren’t present for the final stage of production, they realized the value of handling business in person and fostering interpersonal relationships. “You can’t shortcut face time,” they said. “It takes courage to show up.”

The notion of being present — and visible — resurfaced multiple times in conversation, especially in the context of blogging and social media. The women expressed some of the upsides and downsides of having an online presence in their creative work, along with the challenge of maintaining boundaries and balance between their on- and off-line communities and personas.

On Twitter, feminist writer Roxane Gay is very outspoken; her bio says, “if you clap, I clap back.” When asked about her courage on social media, she admitted to being shy in real life. Twitter, she said, gives her bravery and a chance to fire back in the heat of a moment: “My Twitter is the best, baddest version of myself.” But she also noted the challenge of negotiating boundaries, saying that people who follow her think they know her. (Sometimes, she added incredulously, they even think it’s okay to hug her.) Yet she appreciates the sense of comradery, and the fact that online connections strengthen in-person encounters. Gay’s career is indebted, in some ways, to the strength of the online communities she is part of — while living in a rural town and searching for community, she began blogging, eventually growing a massive readership, particularly through essays that reached marginalized groups.

The issue with blogging, Bonney said, is that, “If you are the base of your business, people expect your personal life to be shared. But that can be a difficult line to figure out.” When asked how she handled this balance between public and private life, Joy Cho, who is also very involved in online communities, said that she is conscious of not making her personal life the focus of her work, and not sharing too much about her family’s private life. She aims to share joyful moments: “things that are amazing about being a woman or mother or businesswoman.” The main issue, as Bonney suggested, is how to set boundaries when trying to be transparent.

“I try to be as transparent as possible,” said Angelica Ross. As a transwoman and trans* activist, she stated that it’s important for her supporters to see that her journey “was not all roses.” She is an advocate for #girlslikeus, a Twitter campaign created by Janet Mock that gives transwomen a platform for sharing their stories. For Ross, transparency and openness on the internet are essential, not only to her brand, but to illustrate to people how hard she worked to get where she is today.

Of course, having any sort of internet presence opens you up to hurtful public criticism — this is particularly true if your social media persona is part of your job.

Many of the women admitted to being sensitive souls who, because their work is so personal to their lives and cultures, can’t help but internalize and feel wounded by abuse on the internet. Aguiñiga explained that she chooses to stay off social media as much as possible and instead prefers to build her life and artwork around human connection. But at the end of the day, “screennames are just screennames,” Petosky said.

Ross said that she is rarely thrown off by negative comments because she is her own worst critic — no one on the internet can come up with something she hasn’t thought of before. She laughs off the criticism, and said when she reads a critique, she often thinks, “Yeah, I know, girl — I’m working on it!” Lily Stockman echoed this sentiment, expressing that she is undaunted by — and even enjoys — online criticism of her business, because it helps her clarify the company’s message. When people feel passionate enough to voice their concerns regarding ethical textile production in South Asia, she is glad to abide.

High exposure on the internet can also lead to unlicensed copying, a matter of course for women in creative fields. At a fashion show, Bethany Yellowtail discovered that her grandmother’s unique tribal design had been copied by another brand. Devastated, she immediately regretted publicizing the design on her website, but later recognized it as a chance to break the mold in the fashion industry. Bethany now consults for companies that want to work with Indigenous designers, bridging the gap between cultures.

Angelica Ross remarked that copycats push you to keep pushing the boundaries of your own work, and Roxane Gay said she is flattered and excited by the enthusiasm of younger feminists who write in the same vein as her book Bad Feminist. Some amount of imitation, she said, is unavoidable in the field of writing.

Bonney asked all eight women was what success meant to them and whether they felt they were successful. Unsurprisingly, having highlighted the importance of work-life balance, their conception of success blended the financial and the personal — with the latter overpowering the former, in most cases. For Tanya Aguiñiga, being successful meant having a higher purpose in mind and being able to connect to her community. “It’s not about money,” she said, “it’s about purpose.”

Lily Stockman and Joy Cho both shared Aguiñiga’s opinion; Stockman shared a story of a recent health scare that had helped her reevaluate her priorities, saying she had conflated financial success with happiness. Cho said success, to her, meant being a good role model for her daughters.

Shadi Petosky and Angelica Ross both expressed that while they feel successful today, part of them still holds on to their fear of homelessness. Ross said she considers having had an empty bank account a blessing, since it enables her to appreciate each day by counting the “winning moments.” Success, she said, was accepting this mentality. “I’ve had to do a lot of work to get here, to give myself compassion, grace, and a second chance.” She said she feels success in her failures: “As a black trans person, if I can show my failures transparently, then that is a success.”

When asked if she considered herself successful, Gay replied that she feels intellectually successful, but not emotionally: “In my heart it is never enough. I think about the people who say, “she only got it because she’s black, or because she’s queer.” I hear these doubts, so I work harder, relentlessly, and don’t stop.”

Unfortunately, the more powerful and successful a woman is, the more she is scrutinized — our political climate is proof of that. During the final presidential debate this week, Trump called Hillary Clinton “such a nasty woman.” As soon as I heard this, I knew it would be all over the internet, but not, it turns out, in the negative way I imaged. Social media users claimed the hashtag #Nastywoman as their own, making “nasty woman” a viral call for solidarity. People have even started selling “Nasty Woman” t-shirts and hats that say “Make America Nasty Again” and donated some of the proceeds to Planned Parenthood, which Trump wants to defund. The joke was on Trump. This country needs more nasty women, women who do not sacrifice their career goals to try to please men or fit a mold.

To be in the presence of such accomplished female leaders for the evening was an electrifying experience. It made me reflect on the times I was too hesitant to be assertive for fear of being judged, and I thought about opportunities I might have missed. I was inspired by these women for their perseverance and character. It was uplifting to be part of a community of women empowering each other to be successful, however we might define it.