Prologue

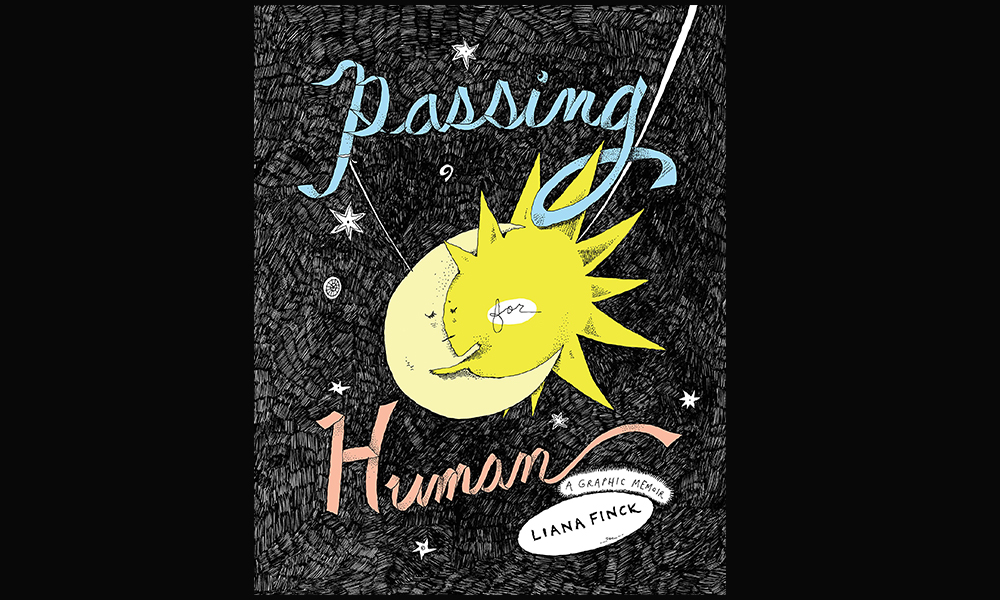

Liana Finck’s ambitious graphic memoir Passing for Human begins with a simple but intriguing introduction: “Once upon a time, I lost something. Let’s call it ‘my shadow.’”

Passing for Human centers around Leola — a sobriquet Finck chose to represent herself — who is on a quest to find her missing shadow. The shadow is a thread that ties the story together. It represents more than one thing: her identity, her “otherness,” and the friendship she has lost with herself over the course of growing up.

Her search begins with a tense coffee date with Mr. Neutral, a boyfriend-type character who appears and vanishes without warning or explanation. Leola is hell-bent on keeping him in her life. While walking home from the rotten date, Leola has an unusual visitor: “the fears that gnaw.” These fears manifest themselves as literal rats that sit on her shoulders, chewing her hair, piquing her anxieties.

With the whimsy of talking rats, dramatically rendered facial expressions, and simple but bold line drawings, Finck presents her lead character as a sensitive and creative woman who has always experienced the world differently from everyone else. She does not feel like she relates to the world and yet reacts to the opinions of other people incredibly deeply. The “fears that gnaw” prey on these sensitivities, bluntly voicing doubt in her ability to keep Mr. Neutral in her life.

We come to learn that Leola’s shadow is her otherness, her sense of identity, but mostly it was the thing that disconnected her from her school friends in her youth. Did she choose to ignore this shadow or did she simply outgrow it? Why does she suddenly, a decade or so later, miss it so much?

Leola desperately tries to remember. Rushing home tearfully, grabbing pens and paper, she finds a new purpose: drawing. “A drawer doesn’t draw because she loves to draw. She doesn’t draw because she draws well. She draws because once she lost something. And by drawing — she will find it again.” For protagonist and author alike, drawing becomes a means of introspection.

Chapter One — Mom

Next, Leola hopes to find her shadow by investigating her ancestry. She starts with her mother, Bess. She knows Bess once also had a shadow and lost it. Maybe by drawing her mother’s story, Leola hopes, she will find out how she lost her own shadow.

Bess’s shadow — drawn as a lifelike silhouette of dark squiggly lines — guards her from bad people and experiences, pushing her toward good. However, despite this helpful presence, under pressure to conform to the expectations of her own mother (Leola’s grandmother), Bess lets go of it. Perhaps, to Bess, her shadow was her artistic spirit.

Without her shadow to protect her, Bess easily falls for any man offering her love and attention — even the bad kind. Finck is incredibly blunt in her visual storytelling here. She brutally illustrates the cruelty of Bess’s unnamed first husband. When he whisks her away to another country shortly after their hasty wedding, the panel shows him carrying her like a suitcase onto the plane, literally treating her like an object. Later, there is a multi-panel sequence of him becoming large and monstrous, growing from bad to worse in his nastiness towards her.

When Bess finds any semblance of happiness outside of their marriage, her unnamed first husband feels threatened. Demoralized, Bess stops looking for happiness for a long time.

With time, though, Bess rediscovers her shadow and escapes the awful union. She blossoms into her true self. But then, without warning, her shadow leaves her forever with one final message for her future: “You are about to do something very grand, Bess.”

Maybe, Leola muses, she had a shadow because her mother once had a shadow. And maybe, one day, her shadow will also remarkably return when she needs it most.

Just as a Leola finishes the first chapter, “the fears that gnaw” reappear on her shoulders. As she prepares for the next chapter, the rats warn her that writing more of her mother’s story will not tell Leola about her own shadow. Fueling her anxiety, they convince Leola to restart the first chapter again, this time about her father’s history.

Finck continues with this unique structure throughout Passing for Human, continually restarting what should be the first chapter of a story that will lead Leola to answers. By the end, Leola creates five different Chapter Ones, each a window into different facets of herself and those closest to her. Rather than reach a conclusive end to any one of the stories, each offers a brief view of her life from a different angle. This nontraditional structure allows Leola to investigate her missing shadow by different angles, hoping that one of them will lead to answers.

Chapter One — Dad

Next, Finck uses Shamai, Leola’s father, to underpin the role labels play in Leola’s self-conception. Leola writes that nowadays you can be given any number of labels: obsessive compulsive, introverted, strange. However, when her father was young, there weren’t labels in that way, and he ran from the thing he feared might render him different from others: his strangeness.

Much like Leola’s mother, in his youth Shamai tried to live a conventional life. He was smart, nice, and not unpopular in school. His shadow was the dark secret he hid, both from the world and from himself. He grew to adulthood having a successful career, a loving wife, and a sweet daughter. He lived his life without pressure to embrace his shadow. That is, until Leola was born.

Finck uses biblical allegory multiple times in her familial history — Job, Ruth, Boaz, and even a female God make appearances. Finck draws a comparison between Shamai and the story of Job. The Devil argues with God that Job is only perfect because he never suffers. “Take away everything he has and you will see — he is nothing.” Job is tested. So is Shamai.

Finck shows panels of Shamai joyfully throwing his new baby Leola in the air. Then suddenly, he notices something. As Leola floats above him, Shamai looks up at her. Their faces grow increasingly nondescript. Shamai says starkly, “I see it in your eyes. I think you have it too. My strangeness.” Maybe, Leola ponders, she inherited her father’s strangeness — his shadow.

When the rats return, Leola admits that she has embellished this story because she desperately wants her weirdness to have a lineage. She wants a label like “strange”: “The labels set you apart from the world. But they also give you a place in it. They make you feel more different, but less alone.”

Chapter One — Leola

Leola discards yet another Chapter One and begins the story of herself. She recalls the singular moments in her past when she was an outsider, and how they affected her. She rapidly abandons this chapter and turns to Mr. Neutral, fixating on how much blame she should apportion to him for her anxieties.

Chapter One — Mr. Neutral

Maybe like many of us, Leola finds a convenient scapegoat in a romantic relationship in order to avoid truly looking inward. Maybe by drawing, she’s starting to connect with herself for the first time since she lost her shadow. Maybe, she realizes, Mr. Neutral does not deserve all the credit for this journey.

Chapter One — Leola’s Shadow

Leola finally understands she’s been living inside her mother’s story her entire life, and she needs her own story to become reality. She writes, “A story only works when it gives shape to something true, something felt. What I mean is life is an ocean, vast, dark and deep. A story is a ship. A ship without water is pointless, dangerous.”

This final Chapter One takes place in the Shadow’s imagined world on the mountain behind Leola’s childhood home. The background is dark and the characters and objects bright white — stylistically exactly opposite of the previous chapters. We learn in this chapter where the Shadow came from and where it disappeared to all this time.

More importantly, we learn more about what it means to be human. Leola has discovered this through the act of drawing. She draws and asks questions. Through this deep investigation of self, she is able to connect with what it means to not just pass as, but to be human. She asks timeless questions. As readers we learn that though the answers may differ from person to person, the questions are how we find our own respective shadows.

Epilogue

Above all, Passing for Human is a story of self-discovery. By blending non-linear structure, magic, and biblical allegory in graphic memoir format, Finck sets herself up for an ambitious task. Her story jumps in and out of real and imagined worlds. She purposefully places Leola in uncomfortable spaces. By doing so, Leola is forced to face herself for the first time in her life, a quest we all must undertake at some point.

Finck’s modus operandi in Passing for Human is to ask the same questions from different angles. Her quest reminds me of my elementary math teachers. They pleaded with us to show our work. They didn’t care much if we got the correct answer; they simply wanted us to show how we got there. This used to annoy the hell out of me. Today I better appreciate the importance of that process. Finck seems to get it too. She stops and restarts. She frustrates. What we might learn from Leola is that the path to self-discovery varies person to person. She is an artist who is still learning how to pass as human in a world that is not always forgiving of women who steer from conventionality. Passing for Human is an impressive work of introspection. It is candid, real, and raw. If you are a human who has ever felt just a little different from the humans around you, I recommend going on Finck’s instructive journey.