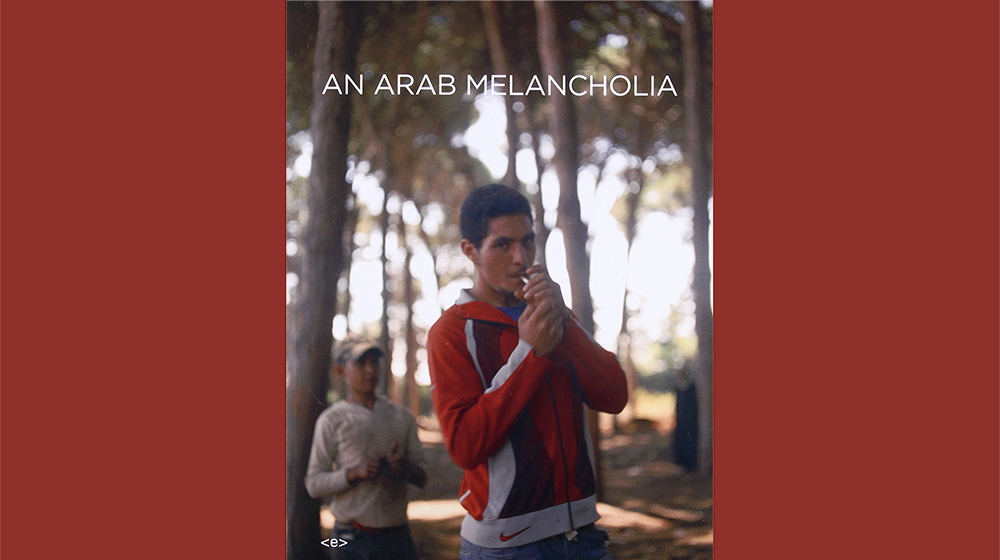

I kept asking him, though he knew nothing about it, to play an important part in my life, to play his part in a love story, to follow my lead, to keep reassuring me. Not to go running off later like so many before him. Not to think of me as a hook up, only a sex partner. I had read too many books, seen too many films. My life and my emotions were more than I could handle. –Abdellah Taïa, An Arab Melancholia

I had read too many books, seen too many films, but none that addressed so aptly the nature of emotions as Abdellah Taïa’s An Arab Melancholia. What it feels like to fall in love: that drug-like state during which everything gets swiped off the table and all you can think of is them.

I first heard Taïa’s name in 2009 or 2010 as articles filled my computer screen with news of “the first Moroccan to come out as gay.” Other times, “the first Arab Man…” was written, headline-like. An open letter to his chère famille had recently been published in the Moroccan publication Tel Quel, in which Taïa evokes his upbringing and his desire for other men.

Some years after reading the letter I came to his autobiographical novel Une mélancolie arabe [An Arab Melancholia], an account of being here and there, working on film sets in France and Egypt and Morocco. And more importantly: an account of the bodies and souls Taïa has been entwined with, such as Javier and Slimane, two lovers haunting the novel. Lovers that have left these invisible marks which we call feelings. And the music, the images it creates.

In An Arab Melancholia, Taïa places himself — not merely his writing, but his whole being — within an affective lineage of writers and artists who remain mostly unnamed. What interests me is the way he attributes his conception of feelings to the books he’s read, and parses out these feelings through series of images, replicating them. For Taïa, affect isn’t abstract or chemically-produced, but something that is also nurtured in one’s imaginary over time, accompanied by fiction in song and writing. Taïa takes this simple, ages-old premise — literature as window to the inner world — and turns it back out, proposing several analogies to demystify his feelings, likening emotion to a fiction, to a kind of elsewhere or possession.

Indeed, when Taïa’s lover(s) do not reciprocate, his affection is replaced by a debilitating emotion under the guise of love. I see this literary avowal as a form of courage: Taïa’s courage to show that he isn’t always in control, his unconditional choice to embrace his feeling self and to understand its nature.

The story is simple. While working on a film in Marrakech, a timid Abdellah Taïa spots Javier, an aloof Frenchman also on the movie set. Eyes locked on each other, a fling starts. It is upon their separate return to Paris that trouble develops: “My presence didn’t seem to matter. He offered me a drink, sparkling water, then hid behind his computer screen with two urgent emails that he had to send off.” This frustrated love is bookended by two foundational events in Taïa’s life, forming a narrative arc, a driving force. The birth (from childhood trauma) of what Taïa calls a “newfound morality, newfound life,” and his memory of Slimane, “a love that wasn’t love.”

Behind this narrative, there is a rare understanding of the distinct nature of feeling as that which is both very real and hopelessly detached from reality, from the object of desire. “I couldn’t stay like that, with Paris completely indifferent and me starting to feel an extraordinary, totally shattering emotion. I was no longer in control, not on the inside.” Taïa the narrator is drifting but the city never falters. It is in this absolute disconnect between the surging emotion and everything else that I recognize what theorist Sianne Ngai calls “suspended agency,” that moment when negative feeling — rejection, anxiety, envy — takes over and Taïa is no longer in control. There are the feelings — those we see reflected in “the books” — and then there is the world. Hence the possession mentioned earlier, manifesting in Cairo, in Marrakech or in Paris:

[Javier’s] spirit had left me alone while filming. But now that it was just the two of us, his ghost and me, the spirit went back to being a distant master, the master who ordained that I should suffer, that every day I lived would bring nothing more than heartbreak. I was possessed by him.

The other, the object of feeling is a ghost, something which cannot be touched. It takes its subject without warning, an unwanted possession. As Taïa implies, here lies the root of the word possessive: “That’s what you used to tell me, that I was a devil, a demon, an evil spirit that you find yourself in love with. Madly in love. ‘Possessively’ in love with.”

Elsewhere, the idea of “fiction” replaces “possession” to qualify emotion. Taïa writes of his desire for Javier “to play his part in a love story, to follow [his] lead.” Here, this desire is a form of fiction or expectation, it must follow a scripted narrative with its own characters and internal developments. It is a story indeed, something nested between life and fiction: “I was obsessed. With you. I didn’t fight it, didn’t resist the love story that my mind played out at breakneck speed whether you were with me or not.” This is the “fictitious Javier,” the one who Taïa carries around like an amulet. At its most removed, feeling is a simple scenario with a beginning and an end, with no real stage but the imagination.

In a different section, a feeling corresponds to an elsewhere, a vacation, a place other than the here and the now. This is the meaning of distance for Taïa:

…Seeing [Javier] immediately detached and distant helped me understand that the time we had spent together, our glances and our bodies there so attracted, and here so distanced, meant nothing to him…

That wasn’t how I felt.

I knew what I was in for: heartache, aching for an indefinable someone who, even though he didn’t say it, even now, wanted nothing more to do with me.

Marrakech was like a vacation for him.

Javier sees his time with Taïa as a vacation. A night spent together is a pause from daily life, a moment spent away from more urgent responsibility. Here is the disconnect: what one sees as a holiday, unserious, the other sees as continuous with the rest: “that wasn’t how I felt.” What’s effectively at stake in the text is whether the feeling self is a temporary aberration or a continued state.

For Taïa, these love stories blur the lines between real and unreal, tangible and intangible. Scraps of paper and diary notes become “pieces of evidence,” proof that what might have felt like a work of fiction wasn’t one at all. An Arab Melancholia is such a piece of evidence, reveling in the blurred limits of autobiography to shed light on the darker side of affection.