“If libraries hold all the stories that have been told,” writes Rebecca Solnit, “there are ghost libraries of all the stories that have not.” Books amplify voices. They, too, can hide the voiceless. The civil rights activist Audre Lorde knew the danger of those untold stories and warned: “Your silence will not protect you […] Black and white, old and young, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual, we all share a war against the tyrannies of silence.”

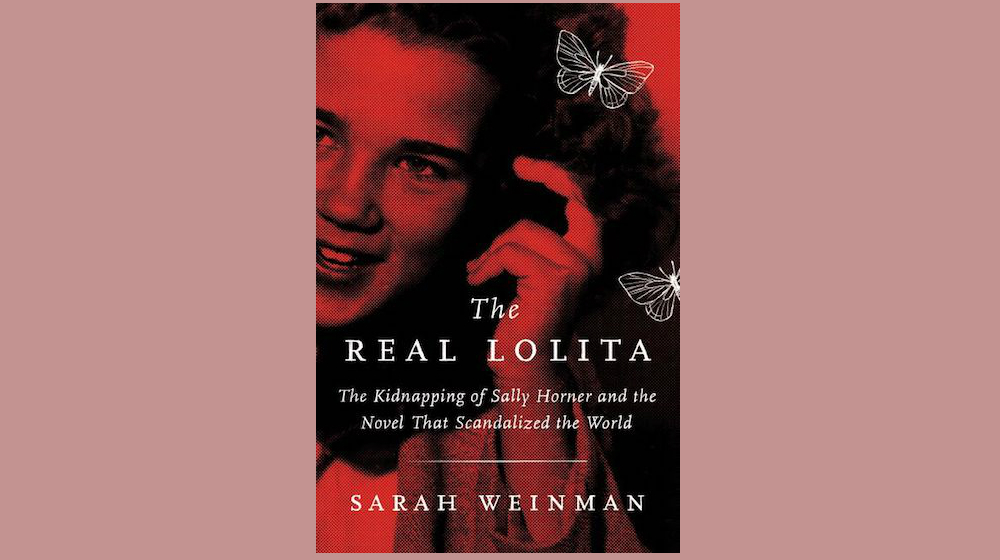

The Real Lolita by Sarah Weinman is a crucial addition to those silenced shelves, a haunting story that has, until now, remained buried in the pages of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita.

Humbert Humbert asks himself, “Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank La Salle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?” From this single line Weinman has unearthed an entire life, far too short and full of tragedy.

Weinman wasn’t the first to question Nabokov’s reference, nor the first to fact-check its veracity. Nabokov delighted in blending fact and fiction. Inventing the name “Sally Horner” wouldn’t phase him. Let’s not forget the text is presented as Humbert Humbert’s memoir, subtitled Confession of a White Widowed Male, edited and introduced by the still-fictional John Ray, Jr., PhD. Humbert Humbert, master gas-lighter, leaves a clue. Caught lusting after his wife’s daughter, he says to her, quietly, “You are crazy, Charlotte. The notes you found were fragments of a novel. Your name and hers were put in by mere chance. Just because they came handy.”

Sally Horner was not a name that came in handy. Nabokov is never that simple — hiding deeper meaning in each name, every ripped letter, butterfly net, folded carpet, lock and key. Humbert Humbert calls Lolita “a little ghost in natural colors,” referring, allegedly, to his childhood love Annabel, and — after Weinman’s reporting — that little ghost is also Sally Horner.

“A curious reporter had drawn a line between the real girl and the fictional character in the early 1960s,” Weinman writes, in her introduction, “only to be scoffed at by the Nabokovs.” Nabokov elided explanation, dropping maddening, evaporating clues. In his archive, “letters and diary entries would hint at larger meanings without supporting evidence.” Back in the pages of Lolita, Nabokov shrugs, via Humbert Humbert: “there is always delight in the semitranslucent mystery.” …Gross.

Nearing the novel’s 50th anniversary, a scholar revisited the Sally Horner question. “But neither of those men — the journalist or the academic — thought to look more closely at the brief life of Sally Horner.” Those men couldn’t grasp what Weinman, Lorde, and Solnit all know in their bones: “The ghosts outnumber the books by some unimaginably vast sum.”

The question propelling Weinman’s narrative isn’t whether Nabokov invented or borrowed his story. Artistry was never at stake. He’s masterful, no doubt. The question is: What happened to Sally?

¤

Camden, NJ, 1948: Sally Horner was 10 years old, her front teeth still too big for her smile, when she shoplifted a five-cent notebook to impress a popular clique of girls. Before she could exit Woolworth’s, “she felt a hand grab her arm.” Sally looked up to see “a slender, hawk-faced man. […] A scar sliced his cheek by the right side of his nose, while his shirt collar shrouded another mark on his throat.”

“‘I am an FBI agent,’ the man said to Sally. ‘And you are under arrest.’”

If you aren’t careful, you might think you’re reading sensory-rich fiction, the engaging scene a product of Weinman’s invention. This is Nabokov’s inverse: novel-esque nonfiction. A peek at the notes section reminds us of the depth of Weinman’s archival research: Ohio’s Lima News reported the slimness of Frank La Salle’s face in March 22, 1950. Those scars, mere vehicles for suspense? Certainly not. Weinman cites La Salle’s draft registration card, from 1944.

Weinman has taken her exhaustive research — honorary doctorate, anyone? Cornell? — and woven a masterful dual narrative: part true-crime, part literary criticism. She paints Sally’s short life in full color, even interviewing her living friend and niece. Widely known as an authority on crime fiction, Weinman has previously edited two anthologies, work that prolific novelist Sue Grafton called “fascinating” and “long-overdue.” Weinman’s book is a master class in tension. Chapter by chapter, Weinman shifts the character focus, from Sally to her mother to Nabokov and back, allowing shady details to build and compound, mounting the drama, the fear, toward revelation and tragedy. As in classic crime fiction, The Real Lolita features a tenacious, newly-appointed detective searching for Sally, and in short chapters that end on cliffhangers or revelation, Weinman dares you to put her book down.

Although “writing about Vladimir Nabokov daunted” Weinman — she describes researching his papers as “coming up against an electrified fence designed to keep [her] away from the truth” — I, for one, am grateful she prevailed. The result is a riveting, important book, one that, at long last, places the abused child first.

¤

The Real Lolita opens with a vivid description of a photograph, urging us to look closely at this nine-year-old child, before the sexual abuse and abduction to come: “Tendrils of Sally’s blond hair brush her face and the top shoulder of her coat. She looks straight ahead at the photographer, her sister’s husband, trust and love for him evident in her expression. The photo has a ghostly quality, enhanced by the sepia color and the blurred focus.” Weinman revives Sally Horner, telling her surviving family members, her memory, and the countless others who’ve lived through similar brutality that Sally has value — far beyond a predator’s gaze. Beginning this way is political: say her name; see her face; never again misread Lolita.

The sickeningly ill-chosen blurb on my Vintage paperback calls Lolita, “The only convincing love story of our century.” Thankfully, Mary Gaitskill has already written a take down of the blurb: “For how could anyone call this feeding frenzy of selfishness, devouring, and destruction ‘love’?” How? They’ve fallen under Humbert Humbert’s terrible spell. The very thought turns my stomach. “You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style,” he admits, on page one, his apparent candor a come-hither ruse, his cleverness all pretense.

Weinman, gavel in hand, writes “abuse […] should not be subsumed by dazzling prose, no matter how brilliant.” Of course. And yet, what’s lasting about Nabokov — and the reason Weinman had such important research to undertake — is his brilliant control of language and narrative time. When Humbert Humbert’s prose slows down, we must pay attention. The fleeting instance of licking Lolita’s “rolling salty eyeball” to rid “a speck of something” takes up over half a page, each word churning with tension. Compare this, length-wise, to how Humbert Humbert dismisses his own mother’s death, that eminent parenthetical: “(picnic, lightning).” It’s not only dazzling, it’s Humbert Humbert’s dangerous psychological state, meted out by word count.

Weinman writes to those who have over-simplified Lolita, who hear “Lolita” and still think heart-shaped sunglasses, slick lollipops, scuffed-up saddle shoes, a person, I admit, I used to be.

¤

I first checked Lolita out of the library at 12. I can still picture, so clearly, the librarian’s eyes widen above her narrow glasses. “Do you know what this is about?” she asked, horrified, and when I said, simply, yes, she handed it over. I don’t remember reading the book. I checked it out to look smart and was probably scared off by the word “loins.”

My first real reading was at 17, as a college freshman, around the same age as Sarah Weinman’s first reading, when she admits, her “intellectual curiosity far exceeded her emotional maturity.” Ditto. That Halloween, I dressed as Lolita: I wore a black, wrap midi-skirt, saddle shoes from the kids’ section, peter pan collar, white bow in my hair. I was going to an upperclassman’s party, with English majors, in Brooklyn. When I began to question if it was a bad idea, I told myself Halloween is supposed to be scary. What’s scarier than pedophilia?

Not scarier, but still awful, are the photos of me completely missing the point: pouting, inner lower lip stained blue from a Sparks and a lollipop, playing the role I’d taken too lightly. I met a guy, that night, whom I’d later date. He wore a sweater vest and carried a pipe, called himself a professor, because he was too lazy for a costume, and soon enough, began saying he was dressed as Humbert Humbert. Clearly, at 17, I did not understand Lolita fully, and though I was a smart, careful reader, I was too young for Nabokov’s dangerous game. If I’d had Weinman’s book, if I’d seen Sally Horner’s photographs, something might’ve clicked. Not fire of anyone’s loins. No one’s sin, no one’s soul. Sally Horner. Dolores Haze. Children.

The Real Lolita should be required high school reading, just as In The Heart of the Sea is assigned alongside Moby-Dick. Give the next generation fodder for deeper understanding — and while we’re at it, let’s get the OED to change their definition of Lolita, “Used to designate people and situations resembling those in the novel Lolita, in which a precocious schoolgirl is seduced by a middle-aged man.” Precocious. Seduced? Please.

Nabokov craved close, discerning readers, and famously said, “One cannot read a book: one can only reread it.” Weinman is the best of those re-readers, content not simply with a pen in hand, but an arsenal of archivists, scholars, and sources. Weinman would irk and delight Nabokov.

My only question, now, is: To which ghost will Weinman turn her eye next?