Less than five years after the end of the Civil War, the United States completed the construction of a new wonder of the modern world. Our contemporary understanding of America was arguably transformed less by the war than by the engineering marvel whose 150th anniversary we celebrate today [May 10].

The Union Pacific Railroad covered the easy miles coming west across the prairies, while the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) made the more impressive tracks east through the forbidding Sierra Nevadas. To achieve this spectacular feat, the Central Pacific employed almost exclusively Chinese laborers. These numbered well in excess of ten thousand, some of whom were responsible for preparing the final tracks for the famous completion ceremony at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869.

But the span of 20 years between the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act saw the rise of a new American nativism. Anti-immigrant sentiments banished those whose tears, sweat and deaths had helped clear its path. Tens of thousands of Chinese workers whose backbreaking labor had brought the railroad into being, including many who lost their lives, were expunged from history and eventually refused citizenship.

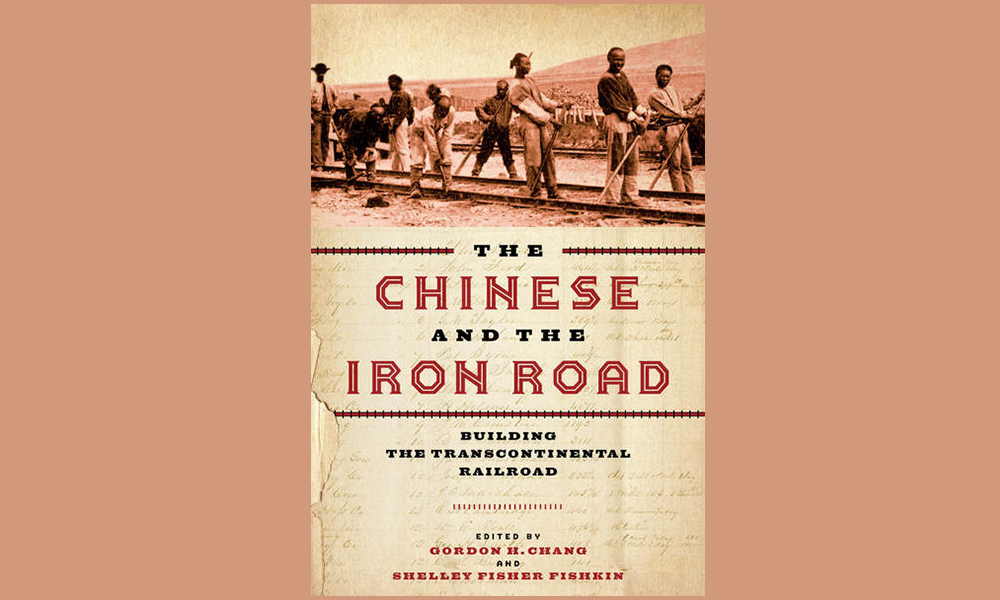

Working from a Stanford University initiative — the Chinese Railroad Workers in North American Project — Gordon H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin have put together a substantial collection of essays testifying to the experiences and the effects of a population whose efforts were denigrated at their time and erased afterward. Though sometimes dry in an academic way, and sometimes speculative — Evelyn Hu-Dehart discusses possible parallels with contemporary labor migration from southern China to Cuba — the essays provide a fascinating insight into the life of Chinese railroad workers and the imprints of their presence.

We find out how “John Chinaman” was treated, how he built communities in America, how remittances from America changed the face of Chinese life back home, how Native Americans and Chinese workers interacted along the route of the railroad, how railroad workers brought new words and new cultural practices to America and took others back to China. How, in fact, beyond glaring influences like San Francisco’s Chinatown, Chinese migrant labor in America from the Gold Rush to the rail push made subtle but significant changes to the culture of the entire Pacific Rim.

Providing this rescued testimony is a struggle in itself as the material and written record of these workers is scant at best. Partly due to linguistic, racial, and cultural difference — as well as the lack of respect shown them by the authorities — there is a dearth of the usual historical evidence to explain what Chinese workers’ lives were like and what they thought. They were treated worse than other workers, paid less for doing more, and, unlike other workers, responsible for paying their own food and board. Insofar as it’s possible to measure (and it was possible, in terms of tracks laid over similar terrain) they were also significantly more effective than colleagues from other countries.

They did the work by hand, including, legendarily, lowering each other down in baskets by ropes to place explosives as they cut through the Sierra Nevada. Thousands died. The others survived freezing weather, dangerous work, epic storms, and the wrath of Leland Stanford whose financial stake in the Central Pacific was threatened by their peaceful but largely unsuccessful strike of 1867.

There are no extant letters from the workers who came, mostly from southern China, to find enough wealth at what they called “jinshan” or Gold Mountain to fill their families’ rice bowls. The ephemeral nature of the work camps — often remote and abandoned as the railroad moved on — meant few enduring settlements. The disinterest of the Central Pacific in the life and concerns of its Chinese workers and subsequent anti-foreigner prejudice led to an empty transcript. And the social and cultural revolutions in China meant that much of what was sent or taken home has not survived. Nevertheless The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad is a successful attempt to make visible and known the profound, and broad, contribution of Chinese railroad workers.

In a related, individual project, Chang has simplified the story of these workers in a new book, Ghosts of Gold Mountain, to make it more accessible. But the researchers in this scholarly volume deploy a myriad of techniques to bring a hidden, multi-dimensional history to life. Archaeologists literally put history together piece by piece from sites such as that around Promontory Summit or “along twenty-two miles of the historic SPRR alignment” on which Chinese worked after the CPRR. Oral historians Zhang Guoxiong and Hsinya Huang use interviews and community legends to add color to circumstantial evidence of the workers’ reception by their home villages and Native Americans respectively. And Denise Khor trawled through the photographic record to find examples of shots that included Chinese laborers. Even when these photographs were reproduced, the workers were marginalized as primitive. She quotes scholar Deirdre Murphy, “‘Like sentinels of industrial change posted between the locomotive and the natural landscape, the Chinese workers witness and react to the mechanical velocity of the railroad even as it leaves them behind.’”

Although not all laborers were successful — some died as in America or returned and died in penury at home — enough wealth flowed home through returning prodigals or remittances to fuel legends of wealthy uncles returned from “jinshan” to build a village.

Greg Robinson records the comments of European travelers about this distinct population. The anxieties about “belonging” that led to the Exclusion Act stemmed from a fluidity of identification that is obvious in how Europeans wrote about the Chinese. Robinson notes that “the Chinese railroad worker could simultaneously represent widely divergent ideas about race, immigration and nation…” On the one hand, Chinese laborers seen as “coolies” represented the “worst excesses of American capitalism and racialized labor.” On the other, the noble railroad laborer overcoming nature for nation could “embody ideas of American modernity and progress.”

From Chang and Fisher Fishkin’s volume we discover what workers ate, drank, earned, believed — and where their materials came from. As well as using local produce and goods, archaeological evidence shows that some foodstuffs came from China through well-established trading companies. Ritual statues in or near camp sites point to specific religious practices and, bizarrely, Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce bottles are evidence of global trade (and the British involvement in China).

When Stanford knocked in the final spike of the railroad, it completed a loop that triggered a telegraph message coast-to-coast: “DONE.” Though this book completes another long loop toward this research at the university that bears his name, the work is anything but “DONE.” The Chinese and the Iron Road begins a restoration of the stories of the awe-inspiring contribution of Chinese workers, but the stock has only just begun rolling.