See to it that no one takes you captive through hollow philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ.

Colossians 2:6-12

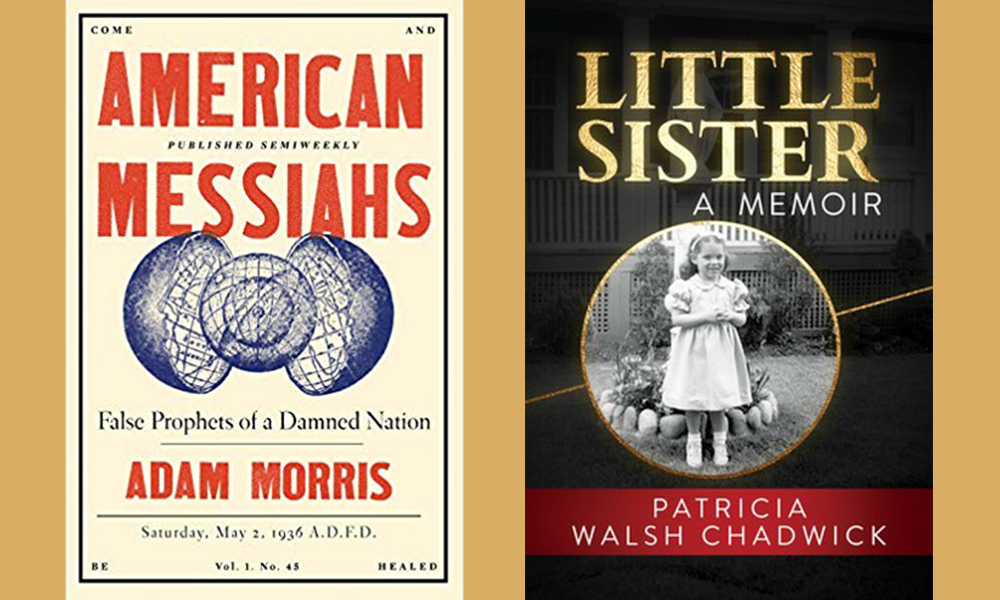

— Little Sister. Patricia Walsh Chadwick. Post Hill Press, 2019.

— “Child of the collective.” Noam Shpancer. The Guardian, February 18, 2011.

— “My Childhood in a Cult.” Guinevere Turner. New Yorker, May 6, 2019.

— American Messiahs: False Prophets of a Damned Nation. Adam Morris. Liveright Books, 2019.

The books and articles above represent a recent flurry of disclosures about what cults are all about and what it is like to grow up in one. The three fascinating autobiographies by Chadwick, Shpancer, and Turner paint a mixed picture of the joys and sorrows of growing up in a communal society during their formative years. The more biographical book by Morris is more of an academic review of the major cult figures in American history, but it provides some useful generalizations about the cultural and sociological forces that led to the emergence of cult leaders, and how they attracted a following. Further, it helps identify group characteristics and practices common to the various cults the three autobiography authors grew up in.

In a recent sermon on the dangers of cults, California pastor Rev. Stewart Perry uses the above quote from Colossians to exhort his congregation to avoid joining one: “see that no one takes you captive… cult leaders are dangerous when they think they have no sin — that’s ‘manipulative crazy’… anyone who thinks they never need forgiveness is very, very dangerous.” Further, he advises his congregation that “Jesus is the antidote to cults… Jesus is enough.”

Perry’s sermon reminded me of another pastor who similarly warned his flock about the dangers of a cult just prior to WWII. Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer cautioned his fellow Germans in a national radio broadcast in 1933 (cut off by the government) that they too risked being taken captive through “empty deceit.” He warned that “they were falling for an idolatrous personality cult,” in the form of Hitler and the Nazi Party. Sadly, Bonhoeffer’s warnings went largely unheeded, and he was executed for his trouble by the Nazis in 1945.

Morris introduces us to some of the more significant messianic or charismatic cult figures in American history, all the way from Jemima Wilkinson in 1776 to Fr. Divine in Harlem in the 1930s, then on to that “visionary with stunning charisma” and a “holy-rolling Marxist” Rev. Jim Jones in the 1970s, whose followers ended up in a mass suicide in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978. A comparable fate befell David Koresh, leader of an apocalyptic religious sect known as the Branch Davidians, when he and 75 followers perished in a firestorm in April 1993, while their compound in Waco, TX was under siege by FBI and ATF agents. Morris uses these examples to argue that American messianic movements represented quasi-biblical communalism — the practice of communal living which is a “repudiation of the values and institutions that Americans hold dear” (e.g. the “sacrosanct individualism on which American culture thrives, but also the nuclear family unit that evolved alongside industrial capitalism”). This kind of cultish communalism, Morris points out, was often associated with celibacy, a rejection of marriage, childbearing, and traditional kinship structures.

Breaking with traditional social customs is common to many cults. When Governor Ronald Reagan began cutting social services in California in the 1970s, Rev. Jones’ Peoples Temple members earned a charitable reputation for housing foster children. Morris is less sanguine about the underlying motivation, believing that Jones’s objective was to “undermine and then delegitimize the nuclear family….” Jones discouraged most marital unions as “counterrevolutionary and bourgeois” and too “possessive”; as a result, “he began to take many sexual partners besides his wife.”

The nuclear family structure, however, remains resilient. It has endured for millennia despite numerous attempts by disenchanted messiahs and self-proclaimed prophets to replace it with something else. Some of those attempts have been relatively innocuous, like the Hippie movement of the 1960s, which used the Timothy Leary mantra of “turn on, tune in, drop out” to form “druggie” communes in places like Vermont, where they practiced communal living and child rearing in a nose-thumbing, anti-establishment gesture. Other attempts at replacing the emphasis on nuclear families with communal living and child rearing would include the semi-official, more socially sanctioned kind of communalism practiced in Israeli kibbutzes after WWII. As Noam Shpancer interprets his growing up in a kibbutz, it was “born of an exuberant meshing of Marxist and Zionist passions” in Israel, with widespread economic, political, and cultural influence. Ideologically, kibbutz members wanted to break away from “old Jewish-European traditions… They wanted to demolish the nuclear family structure in favour of the group… There was also a feminist motive, as communal sleeping [for children] was supposed to free women to participate equally in community life.”

The separation of parents and children was hard for Shpancer, as it was for Chadwick and Turner:

As children, we spent most of our time in the children’s house with our peers. We ate, played, studied and slept there. We would visit our parents every afternoon between 4 p.m. and 8 p.m., then they would return us to the children’s house to sleep. Our Jewish mothers never cooked us a meal, never washed our clothes or sang us a lullaby. The kibbutz system sought to limit private intimacies in case they diverted members’ energy from the communal project.

There was a darker side to Kibbutz life, too — “the pressure to conform was relentless.” Like Morris’ observations, “individuality and competition were looked down upon,” claims Shpancer.

Not every heavenward gazing cult was without sin, and instances of very earthly abuse (physical, psychological, or sexual) are found in all three autobiographies. As Shpancer relates, “Years later it also came out that a girl a few years ahead of me had been molested repeatedly by one of the members, the father of another girl.” For the introverted kibbutz, evil was something outside, like capitalism or the corrupt world. Using words that ring awfully true in the 21st century, Shpancer claims that if anyone suspected any wrongdoing, they probably chose to look away: “When a dream is prized, we often look away from any reality that threatens to undermine it.”

Shpancer points to another commonality shared by children of cults, even those as enlightened as kibbutzim — no graduate or survivor wants to repeat the experience with their own nuclear family. By the 1990s, “most kibbutzim had already turned away from communal sleeping. The move was in large part driven by women who grew up in the children’s house and, having become mothers, refused to let their children experience that same system.”

In her recent New Yorker “True Confessions” revelations, Guinevere Turner also recounts her lifelong struggle to come to terms with her cult upbringing: “I was born into a family of a hundred adults and sixty children in 1968, and spent the first eleven years of my life among them.” That family was the Lyman Family, under the leadership of yet another charismatic male, Mel Lyman, who had Family compounds all over the United States. Turner spent much of her childhood in old buses, crisscrossing the country.

An older member later explains the “mooney” Lyman Family rationale to a 12-year-old Turner: “We work at it, striving for inner consciousness, self-development on the inside instead of the outside. This life we live is not for everyone, only if you have Mel inside of you.” The Family also preached that the apocalyptic “Big Confrontation” was coming when a spaceship would arrive to take all the members to Venus.

Her single mom birthed Turner into the Lyman cult at age 19, and she stayed until age 11, when she was kicked out to join her mother, who had left the Lyman compound in Manhattan to rejoin her own mother in New Jersey. At the time, Turner was in another Family compound in Kansas: “Children and their biological parents tended to be separated early on in the Family, and I was no exception. My mother and I were rarely on the same compound, and I didn’t know her very well.”

Turner was heartbroken to leave her childhood friends and the only family she had ever known. She was traumatized by the thought of having to interact with the “soulless” World People outside. It was only much later, after high school and college, that being a writer helped her confront the darker side of the Lyman Family. Once again, familiar trends and patterns are revealed.

For one thing, Tuner finally recognized the patriarchal nature of the Family, where women waited on the men, and the latter often took 13-year-old girls to be their own private concubines. And, as in other cults, Turner experienced severe physical and psychological punishment, negative experiences which she conveniently repressed for many years while fondly remembering the better times.

From the perspective of 50 years of age, Turner concludes: “There will always be people in search of what cults have to offer — structure, solidarity, a kind of hope.”

Perhaps the most remarkable of the three autobiographies is Chadwick’s Little Sister, written, like Turner’s, from the perspective of age and acquired wisdom. Like Turner and Shpancer, Chadwick has fond memories of the friendships she made inside the Catholic cult where she spent most of her formative years, until at age 18, after finishing high school, she too was kicked out because she did not have “the makings of a nun.”

What is remarkable about Chadwick’s memoir is that there was no need to find or invent an ideology to rationalize the cult’s existence, as Morris argues for many of the cults he reviews. The religious ideology came ready-made in the form of the teachings of the Catholic Church. Nor were the members illiterate, uneducated “moonies” who would have followed their charismatic leaders anywhere, unquestioningly. Instead, they were academics and intellectuals from Harvard, Radcliffe, and Boston College in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s who made a conscious decision to transform their nuclear family lives immutably to follow their own charismatic leader, Fr. Leonard Feeney, a Jesuit priest and mesmerizing orator..

The Catholic cult of Chadwick’s childhood began in the St. Benedict Center in Cambridge, MA, just across from the Catholic Chaplaincy in St. Paul’s Church in Harvard Square. Established in 1940 by a staunch Catholic, Mrs. Catherine Clarke (later to be known as Mother Catherine), the Center became a popular meeting place for young students. She was soon able to obtain the services of renowned Jesuit writer, Leonard Feeney, as the Center’s spiritual director. Before long his weekly lectures at the Center were attracting SRO crowds of hundreds of young people, Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Chadwick’s parents met and married at the Center in 1947, and over the next eight years she and her four siblings all started life within the ambit of the Center.

But Feeney’s public views on non-Catholics and Jews soon got him into trouble. He preached a doctrine of “No salvation outside the Church” and was virulently anti-Semitic in his claims that the Jews killed Jesus. By 1949 the Vatican had had enough, and Boston’s Cardinal Cushing excommunicated Feeney in April, 1949. That same year, 51 followers of the Center, including students and parents like the Walsh’s, established themselves as a religious order, with Feeney as their spiritual director. They called themselves “Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary” and pledged blind obedience to their charismatic leader.

Between 1949 and 1954, membership in the St. Benedict Center expanded to 100 members, including single men and women, as well as married couples who brought and raised 39 children within its orbit. Those members unselfishly sold homes and personal property to donate to the cause, enabling Mother Catherine to buy a compound of seven houses on Putnam Ave., just a few blocks from Harvard Square. That compound became the first incarnation of the St Benedict Center as a cult community. Adults began to dress alike in black suits and dresses, changed their names to saints’ names, and soon (like Shpancer’s kibbutzim) children were separated from their families, assigned to sleep in dormitory-style rooms inside the compound. Their “angel” or supervisor was Sister Matilda (a mother with five children) who did not hesitate to belt her charges across the face with her open hand as a punishment for alleged infractions.

For the children, things went further downhill when, in 1958, Mother Catherine purchased a farm out in the Still River community in central Massachusetts, with eight acres of property stretching down to the Nashua river. This became the permanent home for the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and still exists to this day.

The space and the isolation of the Still River farm allowed Mother Catherine to run the Center as the little fiefdom she had always wanted. Feeney left all the administration to Catherine, and she ran it with an iron fist. She quickly became Chadwick’s nemesis; they argued on issues ranging from personal freedom to communication with her parents, which was forbidden, except for one weekly “family time.” Eventually brothers were separated from sisters, parents from children, and husbands from wives via vows of celibacy.

At times, Little Sister reminded me of Iris Murdoch’s novel The Bell, where a group of lay people in England try to lead a more ascetic Catholic life in the grounds of a convent occupied by cloistered nuns. But Murdoch’s characters maintain a healthy relationship with the outside world, while the Still River community (like Turner’s) regarded the outside world as apostates and “pious frauds” to be avoided.

Little Sister is primarily a book of description, not explanation. Halfway through, I kept wondering why such highly educated people were playing at being nuns and monks in such an ascetic, self-negating way. We must wait until Chadwick’s parents’ 25th wedding anniversary before their daughter asks them the same question. Their weak response is that they were being true both to their Catholic faith and to the vows of obedience they had made to Fr. Feeney.

Two-thirds of Chadwick’s book centers on her struggle to maintain a sense of identity inside a cult which, like Shpancer’s kibbutzim and Turner’s Lyman Family, tried to erase any sense of personal identity or individualism for the good of the common cause. When she finally leaves Still River at age 18 and goes back to establish a life in Cambridge, she has to find herself all over again. After collective childhoods which stressed conformity of behavior and unity of belief, all these authors attest to their later difficulty in acquiring a healthy sense of self.