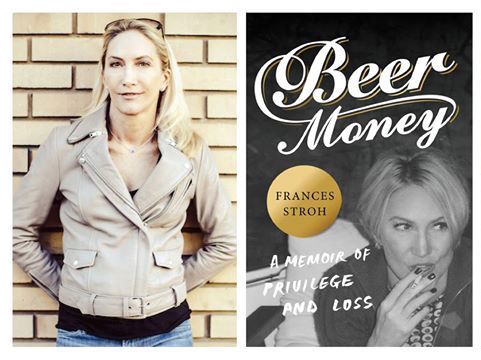

Frances Stroh’s memoir Beer Money: A Memoir of Privilege and Loss details the hijinks of the indulgent and entitled cast of characters who are heirs to their family’s eponymous beer fortune. Stroh depicts her family with care, but like other memoirs and biographies of privilege — Sean Wilsey’s Oh the Glory of it All, Rich Cohen’s Sweet and Low, Jerry Oppenheimer’s Crazy Rich come to mind — the enjoyment of basking in voyeuristic splendor is overshadowed slightly by the incredulity of reading about rich people who are oblivious to other people’s problems. Beer Money portrays the stereotypical dysfunctional rich kid lifestyle: the characters are the children of narcissists and addicts; they are raised by loving or malevolent nannies; they watch their siblings be favored or scorned; they are sent to tony boarding schools (sometimes only to be expelled); they spend their quickly acquired cash on copious amounts of drugs and travel to luxurious locations (someone always seems to be traveling on the Concorde between New York and Paris); they suffer at the hands of cartoon-like evil step-parents; they see wealth slip from their reach, either plundered or withheld; they squander their prospects through idleness or ineptitude and redeem themselves by not being as idle and inept as they were raised to believe they were; they live through tragedies that will be seen by the 99% as not all that tragic. Beer Money made me laugh, cry, and cringe in equal measure.

On the surface, Beer Money is the story of how the family behind the Stroh Brewing Company loses their fortune. This isn’t a spoiler because Stroh lets readers know up front that the family business — and their riches — goes down in a blaze of glory. In truth, the family fortune never feels quite solid; as a fifth-generation Stroh, the family-run company was already in decline by the time of Frances’s birth. And yet, the extravagance of her childhood is portrayed as a birthright. Although one might expect the family’s diminishing prospects to be shown in the context of Detroit’s decaying landscape, for Stroh it seems almost incidental. The greatest connection between their linked fates was being told to roll up the car windows when driving through Detroit’s poorest neighborhoods.

The missed opportunity to reflect on the world at large, however, is not the most glaring weak spot in Beer Money. Stroh’s unquestioning love for her narcissistic, irresponsible, alcoholic father — who married one of her high school classmates, ruled their home through fear and deliberately squandered their inheritance — is. That Stroh recounts her father’s unending new car purchases, extravagant travel and profligate shopping trips to London to buy antique firearms with affection makes it all the more galling. You don’t need to be an economist to see where it’s all heading. It can’t and doesn’t last. And yet, Stroh can scarcely bring herself to utter a critical word against the father of whom she was “the favorite.”

And just when you think Stroh’s father will play the role of Creon, the tragic ruler of Thebes whose selfishness drives his children to ruin, we meet Stroh’s brother Charlie. Always in the shadow of his older brother Peter, Charlie is emblematic of the Stroh’s demise. Arrested for dealing cocaine in college, he eventually succumbs to addiction and all its attendant ugliness. Ashamed of his degeneracy, the Strohs abandon him. In one of the most painful scenes in the book, Stroh details her last sighting of Charlie: she and her mother spy on him in an airport but don’t call out to him. She is rattled by the incident — it sends her running for the airplane bathroom — but she does nothing. We watch aghast as a family with near-unlimited means cannot summon the wherewithal or goodwill to support their struggling son.

As a sharply rendered glimpse into a world most people never see, Beer Money lavishly details the benefits of privilege. With Stroh, we play backgammon at yacht clubs, drink martinis in members-only lounges, visit homes filled with “shiny valuables” too precious to touch, and live among the “richest, oldest families” in Detroit including the Fords, the Chryslers, and the Goodyears. Thanks to a slice of a real estate trust fund to which Stroh is entitled, she embarks on all sorts of adventures including stints in London, Greece, and New York. We root for her even though her story reeks of puerile entitlement and we want her to prevail despite a tone that embodies the sociolect of a Valley girl. While we never fear for Stroh’s physical security, which is so clearly protected by her pedigree, her emotional security is another matter.

At its core, Beer Money is about Stroh’s fear of disconnection, which in turn begets the very detachment she most dreads. There is so little love in her book that it is in no way surprising that she ends up estranged from those around her. She gives up her art; rather cavalierly chalks up the demise of her marriage to grief, financial stress, “running a business together” and “having a baby.” At the close she is distanced from her mother and somewhat dispassionately reports that her father dies alone in a hospital. It is not until a scene toward the end of the book, when she and her siblings sort through her deceased father’s home, that we see the essence of her conflict. While divvying up her father’s paintings, she feels her “heart race as if [she] were bidding at an auction.” A less predictable character might lose us at this moment, but Stroh doesn’t for the simple fact that the narrator of her story is so unfalteringly guarded that we never expect insight. It is the allocation of assets that first elicits a mention of Stroh’s heart.

For what it’s worth, Beer Money is not a cautionary memoir. Stroh doesn’t seem to draw any grand conclusions about life and family. She is happy to find small flowers among the weeds — “People were complicated. We failed ourselves, and each other. But we were all here now.” At the same time, Beer Money is about more than just privilege and wealth. It is about the complicated nature of love, family, and the ties that bind. Stroh weaves together biography, history, and memory to create an original portrait of a family whose life in many ways reflected the demise of traditional values in the face of modern lifestyles. Beer Money is a lens for a larger story about the transformation of love, life, and family. It is a meditation on changing social and economic mores, and an attempt to unpack the dynamics of how corporate consolidation and capitalist wealth have impacted the fabric of America. Beer Money provides no grand pronouncements; it is a rich girl’s attempt to come to terms with her family’s dysfunction.

At the heart of Beer Money is what is at stake when we value money and status above love and family. What makes narratives like Beer Money so fascinating is what happens when we bear witness to the wealthy as they experience their undoing. Beer Money is a tragic tale and like all good tragedies, it allows us to see the hubris of others so we might purge our own pity and fear. In Beer Money, Stroh has lovingly gifted us the sordid details of a broken family so we might look on at a safe distance.