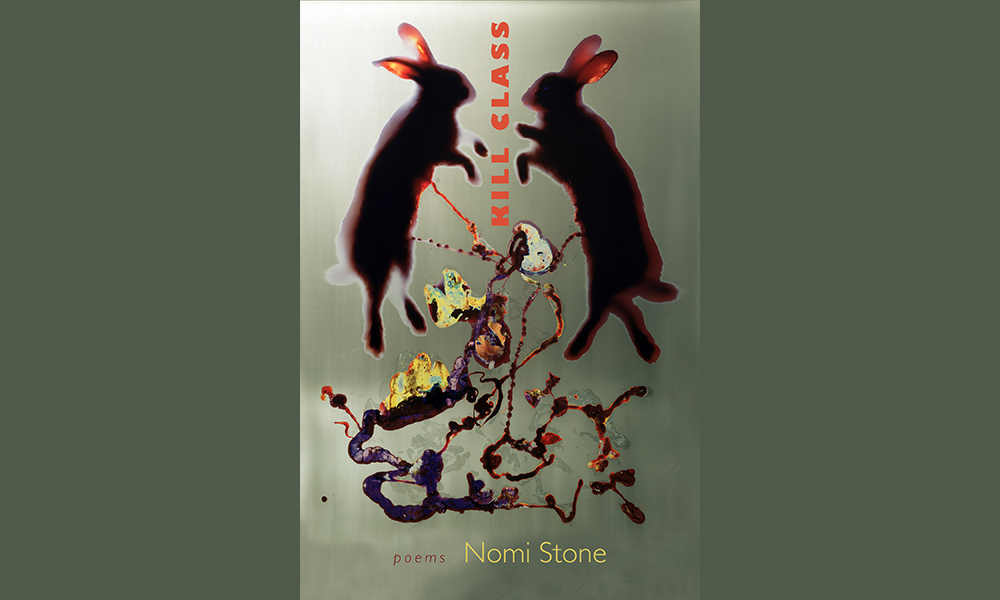

Set among the mock Middle Eastern villages of Pineland, a fictional country in North Carolina built by the US military for pre-deployment exercises, Nomi Stone’s Kill Class is entrenched in a space where acting bleeds into reality. Drawing on her two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Pineland from 2011 to 2013, Stone opens the door to a “war scenario” where “the field glows off and on / like the fluorescent screens of televisions.” At once a play, a game, a cinematic event, and a military exercise, the civilian actors of Pineland are tasked with performing death, betrayal, and loyalty. These civilians are of Middle Eastern descent, a crucial recruitment design that allows the faux villages to stand-in for Iraq. Stone’s critique of mock war resembles Solmaz Sharif’s critical gaze of the language of war in her debut Look, but by investigating an inherently imitative and dissociated set of circumstances, Kill Class asks readers to examine what it means to re-enact violence and how this acting, even if nonlethal, is threatening and dehumanizing.

The speaker in these poems is an anthropologist who alternatively observes and participates in these “war games” herself. In the collection’s opening poem, “Human Technology,” the speaker is told by the soldiers that the army’s task is to cut a line between the people they can trust and those they cannot, or, as Stone describes it, to “slice open the skin of their country: only they / can identify the enemy.” Here, the hired-role players function as metaphorical knives, aiding the Americans in cutting the guerillas from the innocent. While the actors are being objectified (as suggested by the title, they are embodied “technology”), the American soldiers humanize themselves:

Find common ground, the soldiers say. Humanize

yourselves. Classify the norm of who you’re talking to, try

to echo it. Do this for your country, says one soldier, we

are sharks wearing suits of skin. Zip up.

This poem in couplets introduces soldiers who are quick to establish binary thinking: they are “the arm” and the Middle Eastern actors, “they / are the weapon.” Stone’s talent lies in inviting the reader to merge with the anthropologist, the speaker, in a position where interrupting or interjecting is discouraged, so that we must helplessly observe how violence can begin at the level of thought.

The violence depicted in Kill Class exists as a hovering possibility, an ongoing insinuation. We sense it in the poses of the actors pretending to be dead and in the dead animals on the dinner plates of the soldiers. In what appears to be an attempt to simultaneously woo and threaten the speaker, the soldiers in the poem “The Anthropologist” offer their visitor food, specifically barbecue. In a block of a prose poem that breaks to sudden lineation at its end, the anthropologist writes:

It’s true, they take me for BBQ after, ask me if I’m comfortable, do I want dessert and what do I think I know about them and do I know any Americans who went to war or don’t I and if I don’t who do I think I am, and do I agree that through my

stomach, they will get

my heart?

Meat, and specifically eating meat, reappears as a motif throughout the collection, the one literal example of life being lost and consumed by the occupation of Pineland. Proximate to “meat” and “stomach,” the sudden appearance of “heart” stands in for both the speaker’s emotions and the actual, physical muscle. Here, meat becomes the bridge to a body, and another way that Stone cleverly gestures at the thin line between acting out death and death itself.

In “Creation Myth (How Role-Players Came To Speak)” the role-players “slice the Spam into cheeks, break / the bread, then cry! Mouths / light open and shut” around “their words, their words.” Again, food and language sit between the same teeth and seem to be both produced and consumed, provided and fed to the role-players. These short lines recall “The Anthropologist,” wherein meat is also a site of bribery and compliance.

While death in “The Door,” manifests as a “bodiless acre / of graves” a distinct sense of loss builds throughout the collection as the anthropologist continues to parse the language and diets of the soldiers. Stone begins her penultimate poem in the collection, “The Soldier Takes The Anthropologist to the Shooting Range,” by describing the buffet they visit, where “there is so much meat: chicken and fat and cuts of hog, then banana pudding with crumbled cookies.” After shooting at a gun range, they “eat so much it is awful/ almost.” The proximity of guns to meat, and meat to sugar, contribute to the growing connection between mock-violence, gluttony, and the dehumanization of human targets. Stone has invited us to the table in Kill Class, where role-players who “die” at close range “die-in-place” and get “no steak dinner” and those shooting them retire after to go eat just that (and usually more.)

Navigating the space between body and meat, between real death and theatrical dying, Nomi Stone’s Kill Class teaches us that, while Pineland is a fictional country, it is not a fictional “place” altogether; it is actually a deeply American one. The death and survival in Kill Class might be largely psychological, but it also acts directly in creating psychologies that are willing to kill. Because it contains a distinct project, founded in anthropological knowledge and approach, this book walks the line between journalistic ethnography and more conventional poetry. The book’s journey from scenes of fake war to its concluding image of a real massacre shows how violence begins at the level of the word, in the field of language.