Surely the most surreal celebration of Barack Obama’s election happened in the military prison camp known as Guantánamo Bay. In 2008, most of its detainees were held in solitary confinement, but they still talked about the election, using what Mansoor Adayfi, author of Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo, calls “DNN” — the Detainee News Network. They planned a victory party using every opportunity they had: during 10-minute outings in the neighboring cages that made up the rec yard, while laying on their bellies and shouting to each other through the slits under their cell doors, and, for those on hunger strike, by chatting when brought together to be force-fed under the supervision of medical staff, in a bizarre version of the Kaffeeklatsch.

The detainees were not rooting for Obama because of his campaign promise to close Guantánamo. Most had lost hope of that. Instead, they guessed that the white guards who called them “sandn***er” while beating them would not want a Black president.

Late on election night, a Black guard walked in front of the cells of Adayfi’s block. He didn’t say anything — just caught the eye of a watchful detainee, grinned, and touched his own skin. “Obama won!” the detainee started to scream. “It’s the Black House now!” He then covered his cell’s observation window with his towel — a violation of the suicide-prevention rules that triggered guards in riot gear to stomp through every block in the camp, waking all the detainees. This “Code Yellow” was the prearranged signal for an Obama win.

Detainees called congratulations to the Black guards and taunted the white ones, yelling “How do you like your new boss?” The guards screamed back at them, demanding to know how they had gotten the election results. The detainees jokingly replied “It’s classified” — the same response their interrogators gave them when asked what crimes they were accused of committing.

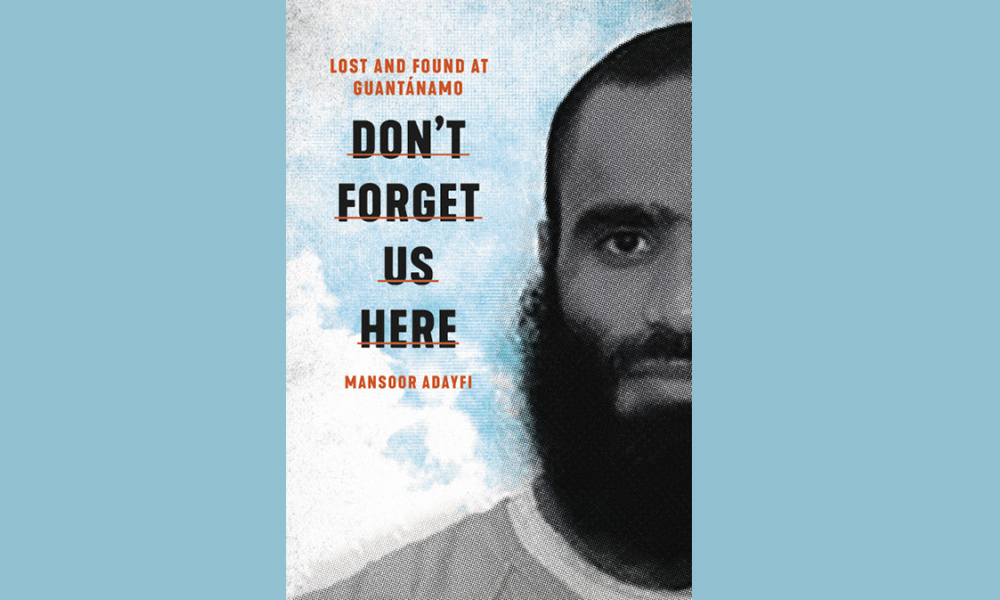

Adayfi, born in a small mountain village in Yemen, learned English during the nearly 15 years he spent at Guantánamo. He was never charged with a crime, but guessed that authorities had mistaken him, an 18-year-old student who spoke a Yemeni dialect of Arabic, for a middle-aged Egyptian al-Qaeda general. Adayfi, like many of his fellow detainees, had been kidnapped and sold to American authorities to claim the large rewards offered in the wake of 9/11. Years passed as they were tortured by interrogators who believed they had not yet cracked, instead of understanding they had nothing to tell.

Adayfi’s memoir is a powerful record of the absurdities of the hell of Guantánamo. I only wish it came with sound buttons, like a children’s book, that readers could press to hear him laughing. He giggles when he starts telling a Guantánamo story, blasts “ha!” when he reaches a good bit, and then, at the end, dissolves into belly laughs that trail off into a sigh. I know this because we’re friends. It’s probably against the rules for me to review my friend’s book, but hey — Guantánamo is a black hole that warps all rules, including the rule of law, into meaninglessness.

I came to know Adayfi when I was curating an exhibition of paintings and sculpture made by detainees in an art class authorized during the Obama administration. Adayfi wrote an essay for the catalog, also published in The New York Times, about why the sea reoccurs so often in this art. It was symbol of freedom and a reminder of beauty, glimpsed only through soon-repaired rips in the tarps blocking the view from their cages. Adayfi and I built a friendship through blurry Skype calls from Serbia, where he now lives, forbidden to return home. “You have to write this down!” I would insist whenever we laughed together the hardest. My favorite story, about learning to cook with no food and love with no one to fall in love with, even became a Modern Love column.

But it was at Guantánamo itself that Adayfi became a writer, beginning in 2007 when detainees were given a pen and paper for 20 minutes a week to write letters. Adayfi, knowing these letters would be scrutinized by the interrogators, took the opportunity to mock them. He wrote to Donald Rumsfeld, claiming he enjoyed being tortured. He invited various congressmen to share a meal of force-fed Ensure. He regretfully informed space aliens that they should not visit Guantánamo unless they wanted to see the worst side of humans. All the letters came back to him stamped “NOT APPROVED.”

Adayfi’s memoir describes the pain and despair of Guantánamo, as when he writes that going on hunger strike “is like entering a dark tunnel, where the light at the end is death.” But the book is also shot through with stories of practical jokes, silly nicknames, and even tales of slapstick humor. The camp authorities could prevent detainees from moving or speaking. But they could not prevent them from laughing. Their laughter was their way of showing, defiantly, that they still retained their humanity. Their laughter refused to accept torture and indefinite detention as serious or rational. Sometimes, Adayfi writes, even the interrogators would start to laugh, “like our collective laughter was an agreement between us of how crazy this situation was.”

On election night, when one detainee joked that they had learned about Obama’s victory from a radio, even more guards poured into the blocks. They violently restrained the detainees and searched every cell, trying to locate this imaginary device. Adayfi, as he often does throughout his memoir, weaves together Guantánamo’s absurdities of pain and laughter:

One thing we had learned about the Americans was that they were really good at overthinking everything. Instead of believing that we were telling the truth all these years, they believed we were trained in special counter-interrogation techniques. Instead of thinking about how the Code Yellow woke up the entire camp, they believed we had somehow built a radio network. Imagine the logic.

Adayfi’s book brings readers a step closer to imagining this perverse logic of Guantánamo, an “upside-down world” where “salt was more valuable than gold, daylight existed only in our dreams, [and] iguanas had more rights than we did.” Adayfi wrote to “capture all the small moments of joy and beauty” that he and his fellow detainees wrung out of their torment.

“Our jokes were the only things we could control,” he explains. “We had to laugh, otherwise we would’ve been paralyzed by fear.” Don’t Forget Us Here is both a record of what was done to detainees and a triumphant boast about how they survived. We should read it to bear witness to what was done in our name — and to gain inspiration for what we need to do to ensure that this injustice never happens again.