The Hammer wants you to know that Sarah Lucas is a powerful woman. Au Naturel, the retrospective of Lucas’s work that moved from New York’s New Museum to the Hammer for the duration of the summer, addresses “the ways in which Lucas’s works engage with crucial debates about gender and power.”

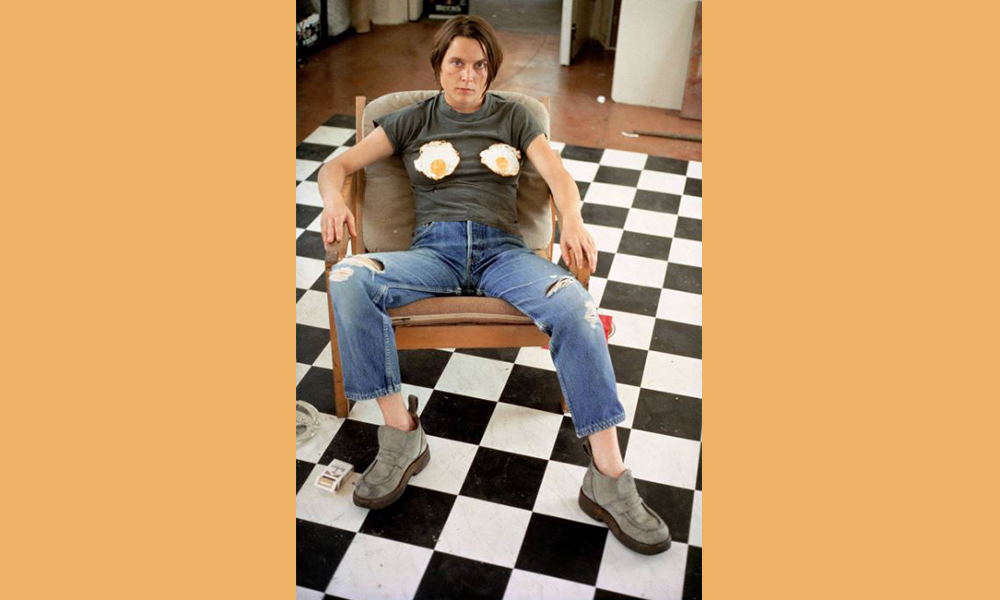

The feature image for the exhibition is Self-Portrait with Fried Eggs, a photograph from 1996 in which Lucas sprawls with self-conscious machismo in an armchair, denim-clad legs spread wide, arms squared at the sides of her body so that her shoulders hunch up to her ears. Her expression is direct and serious, her eyes look straight into the camera, and her mouth is held in a tense line. Balanced on her T-shirt, over her breasts, are two sunny side up eggs, the cheerful yolks at odd angles thanks to their precarious position. In her catalogue essay for the exhibition, Maggie Nelson writes that “Lucas’s work enacts and shares in power.” Lucas, Nelson tells us, wonders “how to be alive — and even more alive — to the power we already have?” As though there is anything remotely powerful about sitting with two fried eggs on your chest. It looks ridiculous. Obviously, says Lucas’s confrontational gaze. She’s practically daring you not to laugh.

Lucas is known for making crude sculptural puns in which human desire is exaggerated, abstracted, and generally made the butt of the joke. In Bunny Gets Snookered (1997) the long-legged “bunnies” made of filled pantyhose hang like lushes over chairs and a pool table, drunken limbs suggestively askew; in Titti Doris (2015), another filled pantyhose piece, a cluster of pendulous breast-like forms sit on top of shapely legs ending in a pair of platform sandals. There are lots of penises or penis stand-ins, as with Eating a Banana (1990), a photograph in which Lucas looks incredulously into the camera, cheeks hollowed mid-bite. Many of her pieces embody the ridiculous idiosyncrasies of the erotic, and while she pays special attention to the aesthetics of mass-market pornographic sex appeal, her pieces are inveterately good-natured. She is far more amused and curious about sexuality than critical of it, despite Au Naturel’s presentation as an inquiry into “power” and how one might get it back, it’s implied, from men.

Perhaps in a bid to prove her work is politically relevant — now an expectation for many artists and museums — Au Naturel situates Lucas’s work as a rebellious feminist dialogue with a male-dominated art lineage. Her many toilet sculptures, for example, are compared to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain for no more substantive reason than that they share the same shape, while pieces like Au Naturel (1994), which emphasize the absurdity of desire by reducing the human body to genitalia composed of food and found objects, were compared to Rene Magritte’s painting Rape (1945), in which a woman’s eyes are replaced with breasts and her mouth with a triangle of public hair.

Lucas herself often rejects such comparisons. When asked to name the first piece of art that mattered to her in an interview with Frieze, she replied, “I’m not making art about art. I didn’t buy a ticket.” Whether or not you take this in good faith — some of Lucas’s Young British Artist (or YBA) counterparts and occasional collaborators include Damien Hurst, Gary Hume, and Tracy Emin — framing her pieces as a clapback between a female artist and the patriarchy is probably what led a friend walking with me to complain that she was “tired of women making art about being objectified.”

It is not difficult to map a political commentary about gendered power onto Lucas’s artwork, which often reduces the female body to sexual organs. Representing heterosexuality so simplistically has invariable cross over with the visual language of misogyny, with its long and manifold tradition. Especially in pieces like Au Naturel (1994), wherein a bucket symbolizes a vagina, it doesn’t take a large leap to wonder if heterosexuality might be inherently exploitative. “One does not violate something by using it for what it is,” Andrea Dworkin concurs on the vagina-as-bucket theory of hetero sex in Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981).

It’s a hot topic for a contemporary museum, but focusing only on a commentary about sexist power dynamics woefully ignores the jouissance that animates her work. This is not to say that humor cannot also be powerful, particularly in its more bracing or brutal forms. Many are now familiar with the adage “Men are afraid women will laugh at them; Women are afraid men will kill them,” which, despite the obvious, still implies there’s a lot to be gained from laughing.

And yet, Lucas’s work has less to do with empowerment than with eros, the total lack of power within the penumbra of the object of desire. Desire always objectifies, after all, and Lucas is a self-described “classic perv.” “Why else,” she writes, “would an artist spend six months, or years, carving, from life, and scaled up to rather large proportions, a plum that looks like a bum? Why would someone knit or crochet only the neck of a roll-neck jumper and call it a ‘Hot Neck’?”

By playing with fetish, Lucas illustrates the helplessness and compulsivity of desire. Infatuation is embarrassing because it robs us of self-control; falling in love is often the first time that our understanding of personal autonomy is truly challenged. Since free will is generally postulated as the original sin that separates us from the rest of the animal kingdom, desire, in all its ridiculous, overwhelming mystery, brings into relief the complications of a mind-body division. Naturally, eros is a hotbed for existential questions. To return again to Au Naturel (1994), the strategic placement of melons and bucket on one side of the mattress and a cucumber and two oranges on the other is a reminder that the seat of all our mysterious, transcendent desire is a material body, and in particular some sensitive nerve endings.

While an existential perspective is inherently destabilizing to any and all power structures, including the ones between men and women, Lucas is too concerned with the absurdity of our situation to aspire to collective action. It is the tension between the transcendent and totally base that centers some of her best work, rather than a political critique. Take Wichser Schicksal (Wanker’s Destiny), a sculpture from 1999, for example. Wanker’s Destiny is an open box raised to eye level, in which an arm ending in a circled fist juts up and down mechanically. The interior sides of the box are covered in mirrors. “The mirror effect was a way of doing something that suggested infinity,” says Lucas of the piece. “My feeling is that wanking is all about time […] the wanking arm looks and feels and sounds, in the head, like a clock. It’s always going on. Somebody else takes over where you left off. It’s like a tune that we all have some inner compulsion to sing along to.”

When struggling with the question of what might connect the disjointed, subjective experience of human consciousness to something greater, we often turn towards art. Its abstraction and refinement theoretically elevates a unified spirit of humanity; the artistic impulse is proof that we are more than little organic robots toiling away until, en masse, our biological imperatives to thrive and survive consume the Earth in a major extinction event. At the least art reassures us that we are compelled by more than the basic pleasures of eating, shitting, or licking each other’s bits.

But with Lucas’s art, compulsion is precisely what brings us into proximity with concepts like eternity and the universal. Desire, betwixt the animal and the spirit, has something to tell us about both. Take the enormous, totemic penis sculptures that compose her Penetralia series (these are not on view at the Hammer, but there are many other larger than life penises on display): these are obviously divine objects, in line with Lucas’s prior statement that she sculpts dicks in part “for religious reasons having to do with the spark.” There’s a long tradition in Western thought of trying to find transcendence by abstaining from the body, but Lucas turns towards it for her own investigation into the Mystery.

“If this is all there is, this world here. If this is it, given infinite possibility, why is it so shabby? […] If we’re so keen to be alive, to survive, why the self-destructive behavior? Why the smoking, drinking, drugging?” Lucas remembers thinking, walking home in the wee hours of the morning through the desolate streets of the Clerkenwell neighborhood of London in the 1990s. It is in this period that Lucas composed pieces with titles like Is Suicide Genetic? as she attempted to figure out what composes fate or free will, what is either lesser or more than human nature. Infinite possibility, and we come out the other side of the evolutionary tunnel blessed with a central nervous system, opposable thumbs, and the ability to orgasm. Re-arrange our DNA ever so slightly, and we could very well be a vegetable platter.

Piercing awareness of the randomness of the universe is terrifying, but for Lucas it is also energizing. “I don’t want to be scared of anything,” Lucas has said. “I hate excuses. Loathe excuses. I don’t want to make them, I don’t want to listen to them, I don’t want to live one.” Maybe this proximity to the senselessness of the so-called universal order is what gives Lucas her sense of humor, her generosity, the spontaneity and wonder that enlivens her work. It is bewildering, being alive. In “Got a salmon on, #3” Lucas poses against a dirty brick wall with the large fish draped from her shoulder down her arm, graffiti scrawling behind her and out of the frame. The shining salmon stands out amidst the dourness of the rest of the photo as a miracle, silver brought to life. At the same time, the inert fish immediately calls to mind the dockyards of England, the fishmonger, grey seas, oily paper, flies. It’s both, not either, and it also looks ridiculous. It’s all a big joke.