This is the 15th in a series of “Provocations,” a LARB series produced in conjunction with “What Cannot Be Said: Freedom of Expression in a Changing World” a conference cosponsored by UCI, USC, and UCLA (January 22 -24, 2016). All contributors are also participants in the conference.

THE N-WORD, one of the most transgressive utterances in the English language, figures centrally in gansta rap, the art form at the heart of the “Rap and Repression” discussion that caps off the What Cannot Be Said: Freedom of Expression in a Changing World conference. For many, the N-word is the linguistic equivalent of the Confederate battle flag; many see both as blood-soaked forms of symbolic communication with deep roots in black oppression.

Yet the relationship of blacks to the N-word is not the same as our relationship to the battle flag–the N-word has been adopted, inverted, and transvalued by significant numbers of black artists (like those featured in “Rap and Repression”), writers, entertainers, and ordinary folk in a way that the Confederate flag has not.

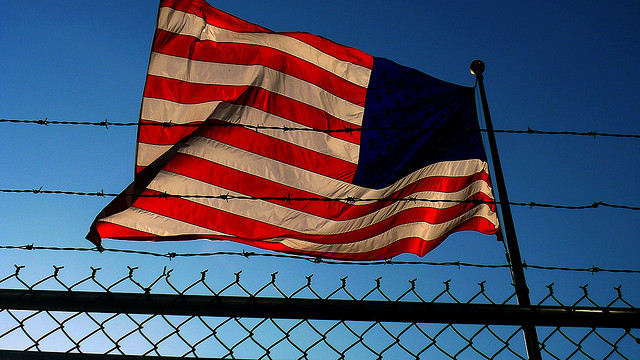

Further, the American flag has been adopted by many blacks despite its own deep roots in slavery, Jim Crow, and racial injustice.

All of which leads to the subject of this provocation: The ability of some words and symbols with ugly historical roots to evolve new meanings while others remain mired in their past uses and applications.

The Confederate battle flag controversy that was ignited by the Emanuel Nine murders reminded me of my debates with my dad about the meaning of flags (and other forms of symbolic communication) and their political role in creating and transforming communities.

My dad was a big black patriot—a six foot eight-inch barrel-chested black veteran of the Second World War and proud Marine who, in the words of America the Beautiful, “more than self his country loved.”

This fact baffled me for years. I couldn’t fathom a black man like my dad pledging allegiance to a flag, and the nation for which it stands, after that very same nation showed its gratitude for his military service by falsely incarcerating him for 22 to 55 years in a state penitentiary for alleged possession and sale of marijuana.

He taught himself the law in prison and found the key to his cell in the warden’s own law books, vindicating himself in a case I now teach in my criminal law class called Armour v. Salisbury; yet his wrongful conviction robbed our family of its sole breadwinner, abruptly reducing a middle class family of eight to crumbs and roaches and rats. I could only attribute his unflagging love for “his” flag, his undying zeal for his own captors and their emblems, to some kind of psychological disability — say, Stockholm syndrome — in which victims sympathetically identify with and even defend and celebrate their abusers.

In time I came to see his patriotic devotion to the American flag not as a mental illness but as a profoundly political act.

Politics in a democracy is about more than merely getting — more than a contest over the distribution of goods and services, over who gets what, when, and how. Democratic politics equally focuses on becoming, and consists critically in the formation of the “us” and the “them” that make unified social action possible.

American and Confederate flags figure centrally in a politics of becoming, for both symbols bond individuals together into a unified “us.” To be more precise, an American or Confederate flag is what language philosophers call a “performative” — a form of symbolic communication that performs (hence its name) a social action, such as bonding individuals together. Words like “I promise,” “I pledge allegiance,” and “With this ring I thee wed” epitomize linguistic bonding performatives; non-linguistic performatives that perform the same social bonding action as promises, pledges of allegiance, and wedding vows include flags, personifications (Uncle Sam), monuments (Mount Rushmore, the Statue of Liberty, Confederate memorials) street names (Martin Luther King and Robert E. Lee), and melodies (purely instrumental versions of the Star Spangled Banner, America the Beautiful, Dixie).

As the Confederate battle flag controversy illustrates, struggles over the meaning of words and symbols play a major role in the process of creating the “us” and “them” of politics. As J. L. Austin pointed out in How to Do Things with Words, performatives don’t simply say something, they do something, and in political communication the thing that bonding performatives such as flags, monuments, melodies, and street names do is unify and rally individuals; they create collective social actors and forge social identities.

The “us” that the American flag originally stood for did not include blacks, who, according to the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Put differently, in terms of race, the “us” and “them” of the American flag before the Civil War was the same “us” and “them” of the original Confederate flag — no Confederate flag was necessary before the war because the Stars and Stripes already stood for an “us” of white American citizens and a “them” of black chattel slaves. It took 600,000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war to transform the American flag into an emblem that includes black folk in its “us” of American citizens.

It took another struggle — the Civil Rights Movement — to make the “us” of the American flag still more racially inclusive. After Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 SCOTUS decision that made separate-but-equal — i.e., Jim Crow segregation — the law of the land, the American flag stood for a racially segregated “us” that in effect (as SCOTUS itself later admitted) made blacks second-class citizens.

In other words, after Plessy, for many Americans the Red, White, and Blue stood for an “us” of first-class citizens who are white and a “them” of second-class black citizens. In the 1950s and 60s, many who adopted, displayed, and embraced the Confederate battle flag resisted including blacks in the “us” of first-class citizens.

Legislation that mandated redesigned state flags across the South incorporating the Confederate battle banner were at least partly responses to SCOTUS desegregation decisions like Brown v. Board of Education and other federal pressures to desegregate. Just as before the Civil War there was no need for a separate Confederate flag to stand for slavery because the American flag itself already stood for that, before the Civil Rights Movement there was no need for a separate Confederate flag to stand for segregation because Old Glory itself stood for that already. At the two crucial turning points in the history of racial justice in America, as the “us” represented by the American flag started to become more inclusive, many lawmakers and ordinary citizens rallied around some version or incorporation of the Confederate flag in support of a more narrow, pinched, exclusive “us.”

Many groups and individuals fly the American and Confederate battle flag together, as if they don’t stand for competing conceptions of “us.” One can contend that the two flags do not stand for contradictory conceptions of “us” if one believes that the battle flag can mean something other than support for segregation or white supremacy—something such as, say, Southern pride. Recent YouGov and CNN polls have found that while more Americans see the battle flag as a symbol of Southern pride than of racism, many more Democrats than Republicans and many more blacks than whites view it as a symbol of racism.

The partisan divide over the meaning of the battle flag illustrates how struggles over the meanings of words and symbols can politically unify and rally individuals. Confederate battle flag critics use the symbol to isolate a “them” of segregationists and white supremacists and to mobilize a racially liberal and inclusive “us.” Many battle flag supporters use the same symbol to distinguish an “us” of folk with Southern pride from a “them” of folk without. Still other battle flag supporters (like the KKK) use the emblem to isolate a “them” of inferior blacks and to mobilize a racially illiberal and exclusionary “us.”

Because no words or symbols have indelible meanings (again, think of the historically vile N-word and the positive uses many blacks have put it to), many different claims can be made about the battle flag’s meaning, none of which are “illogical.” These conflicting claims set the stage for today’s impassioned political struggle over the Confederate flag, whose meaning is a prize in a pitched conflict among groups attempting to describe their social reality, constitute their social identity, and vindicate their social existence.

The flag of my father, the increasingly inclusive American one for which he fought, flatly contradicts the segregationist and white supremacist senses of its Confederate counterpart, which may explain the widely-circulated picture of Dylann Roof, the man who murdered the Emanuel Nine in hopes of jumpstarting a race war, burning an American flag.

My dad knew that the flag he bled for once stood for slavery and Jim Crow, but he also knew that meanings are not fixed and frozen but hotly contested in the process of creating the “us” and “them” of politics and nationhood. The hope and promise of an ever more inclusive “us” is what my dad saluted in the American flag and celebrated on the Fourth of July. The same hope and promise moves me to do the same.

Jody David Armour is the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at the University of Southern California. Armour studies the intersection of race and legal decision making as well as torts and tort reform movements. A widely published scholar and popular lecturer, Professor Armour is a Soros Justice Senior Fellow of The Open Society Institute’s Center on Crime, Communities and Culture. His book Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism: The Hidden Costs of Being Black in America (New York University Press) address three core concerns of the Black Lives Matter movement — namely, racial profiling, police brutality, and mass incarceration. He will participate in the conference Freedom of Expression in a Changing World: What Cannot Be Said.