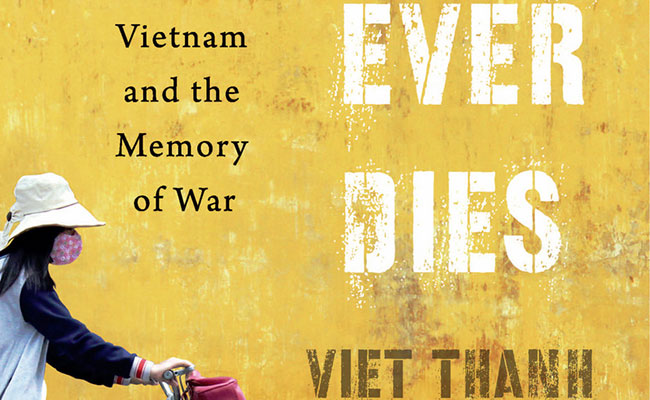

By Viet Thanh Nguyen (author of Pulitzer-Prize winning novel The Sympathizer) for the Provocations series, in conjunction with UCI’s “The Future of Truth” conference

As a Gook, in the eyes of some, I can testify that being remembered as the other is a dismembering experience, what we can call a disremembering. Disremembering is not simply the failure to remember. Disremembering is the unethical and paradoxical mode of forgetting at the same time as remembering, or, from the perspective of the other who is disremembered, of being simultaneously seen and not seen. Disremembering allows someone to see right through the other, an experience rendered so memorably by Ralph Ellison in the opening pages of Invisible Man. His narrator, the titular hero, runs into a white man who refuses to see him, and enraged, strikes back to force the white man to see him. Even beaten, however, the white man refuses to see him the way he wishes to be seen. That is because the other’s use of physical force may make the other visible, but only to turn him into a target. The other must deploy the psychic forces of remembering, imagining, and narrating if the other wishes to transform ways of seeing. Not satisfied with being disremembered, we who are others find that it is up to us to remember ourselves. Having carried ourselves over, or been brought over, from the other side—we Gooks, we goo-goos, we slopes, we dinks, we zipperheads, we slant-eyes, we yellow ones, we brown ones, we Japs, we Chinks, we ragheads, we sand niggers, we Orientals, we who cannot be distinguished between ourselves because we all look alike—we know that the condition of our being and our self-representation is that we are both ourselves and others. We are never without identity and never without ideology, whether we like it or not, whether we acknowledge it or not. Those people who believe themselves to be beyond identity and ideology will, sooner or later, charge us with identity and ideology if we dare to commit that most unnatural act of speaking up and out.

Thus, even though no one has called me, to my face, Gook or any of its equivalents, I know that that epithet exists to be aimed at me. No one had to call me that name, because American culture had already done so through the discourse of the Gook, myself as other struck by the slurs hurled from the airwaves of pop culture. My realization of my racialization, the first sting of a nervous condition untreatable by any type of medicine or surgery, except for the mnemonic kind, arrived early in my adolescence, through jarring encounters with fictions, with other people’s memories. At much too young an age, my pre-teen self read Larry Heinemann’s Close Quarters (1977) and watched Apocalypse Now 1979). I have never forgotten the scene in Close Quarters where American soldiers gang rape a toothless Vietnamese prostitute, holding a gun to her head and giving her the choice of either blowing them all or being blown away. “After that, Claymore Face didn’t come around much, and nobody much cared.” Nor did I ever forget the moment in Apocalypse Now when American sailors massacre a sampan full of civilians, the coup de grace delivered by Captain Willard when he executes the sole survivor— also a woman, since the Vietnamese woman is the ultimate Gook, different from the American soldier through race, culture, and language as well as gender. She is the complete and threatening object of both rapacious desire and murderous fear, the embodiment of the whole mysterious, enticing, forbidding and dangerous country of Vietnam. These accounts of rape and murder were only stories by an author and artist intent on showing, without compromise, the horror of war, but fictional stories are another set of experiences as valid as historical ones. Stories can obliterate as much as weapons can, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard shows in his estimation of Apocalypse Now. Watching the movie, Baudrillard thinks that the war in Vietnam “in itself” perhaps in fact never happened, it is a dream, a baroque dream of napalm and of the tropics, a psychotropic dream that had the goal neither of a victory nor of a policy at stake, but, rather, the sacrificial, excessive deployment of a power already filming itself as it unfolded, perhaps waiting for nothing but consecration by a superfilm, which completes the mass-spectacle effect of this war.

Baudrillard is not aesthetically wrong about the power of the story and the spectacle. He is just morally and ethically wrong. The war did in fact happen, and to suggest otherwise is not so much a critique of Apocalypse Now but an affirmation of the dread power of the western spectacle, a lamentation that does not even acknowledge the real bodies of the dead, only the dead extras on the screen. Toni Morrison’s concept of “rememories,” from her novel Beloved, is useful here not only in clarifying the power of stories to both dismember the living and to bring the dead back to life, but to suggest that something needs to be done about such rememories. A rememory is a memory that inflicts physical and psychic blows; it is a sense that the past has not vanished but is solid as a house, present in all its trauma and malevolence. The most powerful kinds of stories, like Close Quarters and Apocalypse Now, are rememories. Every time I thought of them, I experienced my emotions all over again, intense feelings of disgust, horror, shame, and rage that caused my body to tremble and my voice to shake, an emotional testament to the aesthetic power of these works as well as to their participation in the discourse of the Gook, herself a rememory. It was not that I was forgotten in these stories or that I did not see my reflection; no, I was being disremembered. I saw myself, but as the other, the Gook, and that, I knew, was how others might be seeing me, not just the audiences chortling in movie theaters but even thinkers like Baudrillard, for whom the dead are an abstraction to be dismissed in favor of the more interesting topic, the power of the war machine and its cinematic squadrons.

To be forgotten altogether or to be disremembered—these are the choices left to the Southeast Asians of the former Indochina in the discourse of the Gook, as well as any other Asians unfortunate enough to be mistaken for such a creature.

Provocations is a series produced in conjunction with “The Future of the Truth,” a UCI Forum for the Academy and the Public conference, staged in partnership with LARB, taking place in Irvine on February 3 and 4, 2017.