Some weeks ago I had a terrible nightmare: I was trying to preside over a rowdy campus-wide debate about using Robert’s Rules of Order without an alternative to Robert’s Rules to maintain order. Just at the start of the school year, something disgraceful had been discovered about Henry Martyn Robert. Faculty and students wanted the book banned. Such is the dream life of deans in the age of interrogating history.

To my relief, I read the next morning that Robert was an upstanding citizen, according to the most thorough biographical account available, a master’s thesis by George Hendricks. Robert, born in 1837 to a South Carolina family that moved north before the Civil War, graduated from West Point, fought for the Union, built life-saving fortifications for the Army Corps of Engineers, died in 1923, and is buried in Arlington Cemetery. For good measure, Robert’s abolitionist father, Rev. Joseph Thomas Robert, later became the first President of Morehouse College.

On most campuses, boards and committees rely on Robert’s Rules as a matter of standard practice. I’ve long had a copy on my bookshelf, as have many department chairs and faculty members active in governance. I’m a big fan but did not know the book’s Civil War history — how Henry Robert lost control of a raucous dispute about local defense in a New Bedford church in 1863 for lack of a how-to-run-a-meeting rulebook. We’ve all been here. Robert was smart enough to realize that a guide for civil debate would be useful after the war as citizens assembled in town halls and lodges to exercise self-government. So he wrote one. Following multiple rejections from publishers and after paying for the first print run out of his own pocket, Robert finally had his Pocket Manual of Rules of Order for Deliberative Assemblies published in 1876 by S.C. Griggs & Company. The price was seventy-five cents. It was an immediate bestseller, with hundreds of thousands sold at the time of Robert’s death. Now in its 11th edition, more than ten million have been sold.

Robert’s Rules of Order (the official title since the 1893 3rd edition) offers “a simple explanation of the methods of organizing and conducting the business of societies, conventions, and other deliberative assemblies.” Like a cookbook, it describes what should be done and in what sequence: calling a meeting to order, introducing business, making motions, debating, voting, forming committees, defining the role of officers, determining a quorum. As I tell students, much of the satisfaction of following Robert’s Rules comes from agreeing about the rules themselves. The groups who find Robert’s Rules most helpful are those who know who they are and generally where they want to go but disagree about how to get there. For these groups, the process of making motions keeps the body in motion but does not fracture it.

Groups that are deeply divided may find that Robert’s Rules exacerbates differences, giving power to the side that knows the rules best. We’ve all been here too. In the 1960s, standard procedural maneuvers by Robert’s Rules experts effected two dramatic shifts in student protest movements: the December 1964 late-evening vote by leaders of Students for a Democratic Society to focus on the Vietnam War and the December 1966 late evening SNCC vote to expel all white members (19-18, with 24 abstentions). Under Robert’s Rules, silence equals consent. In tallying all views, parliamentary procedure helps make clear what a participatory body wants itself to be. Arguably, both SDS and SNCC were defined by these votes.

Robert would have approved. He believed that active political participation by young and old was good for America. Accordingly, he wanted his guidebook to be affordable. He directed his publishers to donate royalties to charities and Baptist medical missions. He practiced what he preached: Robert and his wife Helen were active church members, supporting temperance causes, the YMCA, and shelters for unwed mothers. And he understood by the time of the 4th edition (1915) that his name represented value. Indeed, as a brand name, Robert’s is a “goodwill asset” that earns its owner profits in the form of a price premium over the competition in exchange for the owner’s pledge of essential, consistent quality.

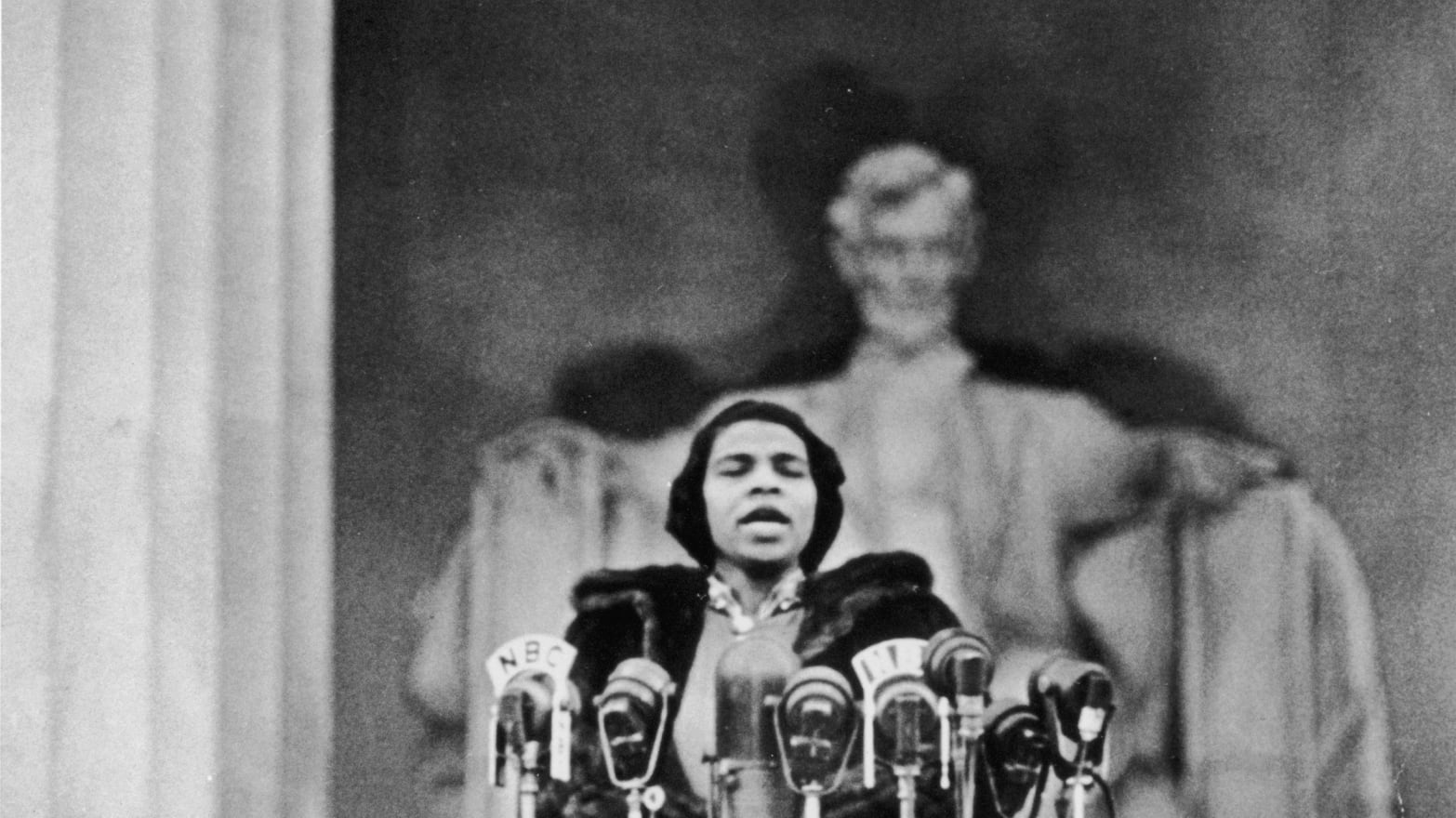

The brand name began to sour for me, however, as I read more deeply into the history of Robert’s Rules. Were the protesters in my dream right after all? I was dismayed to learn the extent to which Robert’s descendants have capitalized on the name, keeping the copyright alive by churning out longer, more complicated, and more expensive editions under the auspices of the Robert’s Rules Association. I was startled to learn that the key figure behind the family moneymaking endeavor was Robert’s daughter-in-law, Sarah Corbin Robert, the President-General of the Daughters of the American Revolution who personally denied Marian Anderson’s request to sing at Constitution Hall in April, 1939 because it was against the DAR’s “white artists only” rules. None of this appears in Robert’s Rules promotional material.

“In the beginning there were no rules except that all events should be of dignity and refinement and not in contradiction to the ideals of the Society,” Sarah Robert explained to the DAR Continental Conference some weeks after Anderson’s recital was moved to the Lincoln Memorial. “[T]here was never a question of one person or one artist. The only question under discussion was whether in view of all existing conditions an exception could be made in rules of long standing… Conditions are the same as when experience dictated the need of the rule.” Which rule would that be exactly? She does not say. In fact, the “white artist only” rule passed by DAR members in 1932 remained in place until 1952, when Dorothy Maynor was “allowed” to sing at Constitution Hall. For many years the DAR was defined by this vote. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR, understanding that silence equaled consent.

My unease about Sarah Robert’s long shadow increased while reading the failed lawsuit of longtime California State University Northridge President James W. Cleary — co-editor of the vastly enlarged 7th edition, Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised (1970), and the 8th edition (1981) — against the Robert’s Rules Association. Cleary had been summarily dropped from the title page of the 9th edition of Robert’s Rules (1990), retaining the name of Sarah Robert, who died in 1972. Cleary had been an advisor on Robert’s Rules since 1965 and had written 15 of the 20 chapters of the 1970 edition. He learned of his dismissal when he saw the book in print. He had been busy expanding CSU Northridge’s campus and diversifying its growing student body. Robert’s Rules Association is a moneymaking family business, not a participatory democracy; Cleary was not given a vote in the matter. Determined not to acquiesce silently, he voiced his opposition in court.

My dream pointed the way to a different truth: I have admiration for Henry Robert but much less now for Robert’s Rules as a brand name, sullied by the dead hand of his daughter-in-law. I’m ready to advocate on my campus against all post-1915 editions (with apologies to Cleary) in part because of her politics and in part because there are plenty of alternatives. My new favorites are Nancy Sylvester’s The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Robert’s Rules, and Alice Sturgis’s The Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure, both of which begin with foundational concepts on which parliamentary procedure is based, gesturing back in the simplest of terms to Henry Martyn Robert’s commitment to civic accord and to binding up the nation’s wounds: all members are equal before the law and minority voices must be heard.