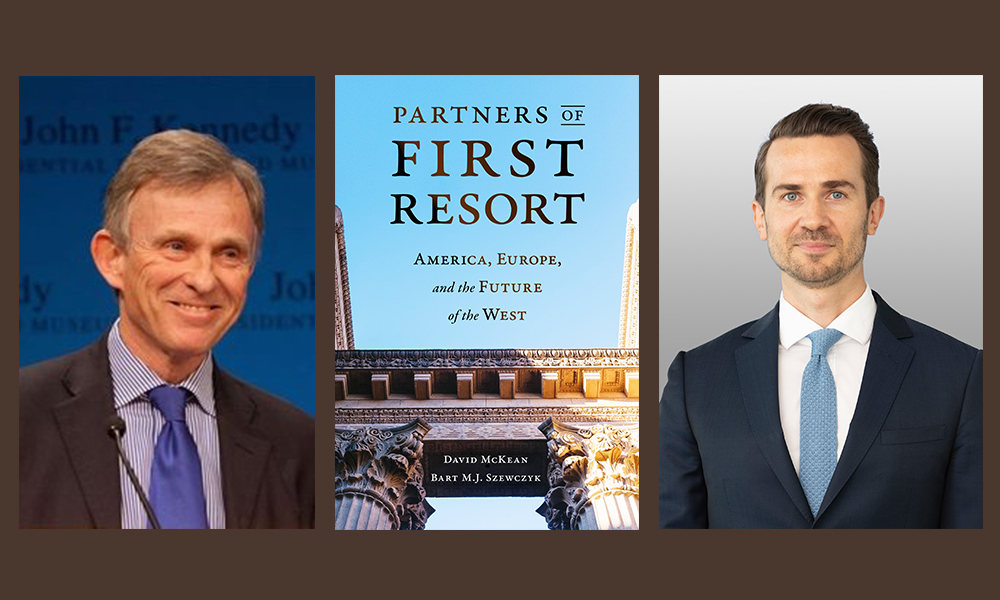

In what ways might the US-EU partnership still provide the “core transatlantic engine to drive the greater process” of global multilateralism? In what ways must transatlantic burden-sharing incorporate not just defense contributions, but also development and diplomatic contributions? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to David McKean and Bart M.J. Szewczyk. This present conversation focuses on their book Partners of First Resort: America, Europe, and the Future of the West. David McKean is a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund. He has served as director of Policy Planning at the US Department of State, and as US ambassador to Luxembourg. Bart M.J. Szewczyk is an adjunct professor at Sciences Po in Paris. He has served on the Policy Planning staff of the US Department of State, and as adviser on global affairs at the European Commission’s think tank.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Before we take up today’s transatlantic partnership, could you flesh out your conception of the broader “liberal order” — perhaps less in terms of a geographic “West,” than in terms of post-Enlightenment political values and economic ideas? And could you contrast the universalizing aspirations for this liberal order in 1989, to the dispiriting associations with de-regulated recklessness by 2008?

DAVID MCKEAN: Sure. In Partners of First Resort we focus on the rules-based order — the norms by which nations of the world interact with one another, hopefully cooperating with each other. Whether in terms of international trade, or resolution of disagreements, or freedom of navigation, or a whole host of issues, these foundational norms and rules have shaped how we function as a global society.

BART SZEWCZYK: For the purposes of our book, concepts of the West, the liberal order, and the free world are interchangeable, and include not only America and Europe but also core allies such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia. Essentially this conception of the liberal order reflects, as you suggested Andy, a set of political and economic ideas originating in Western Europe and North America during the Enlightenment. That’s where the term “liberal” comes in, to encapsulate a specific set of institutions, rules, and norms that promote liberty — based around democracy, market economy, rule of law, free trade, and human rights. In the 1990s, after the Cold War, many policymakers and intellectuals and businesspeople had a vision of liberal democracy and market capitalism as universal models, steadily spreading around the world, including to Russia and China. Nowadays, we’ve grown a bit more circumspect in terms of the liberal order’s scope. But we want to make sure, even if this order doesn’t become universal in the near term, that we protect it where it does exist, and gradually expand it where possible.

So in terms of a “realistic future strategy” recognizing that Russia or China likely won’t democratize, in our sense, anytime soon, could you sketch a basic strategic framework for fortifying this liberal order’s internal strength, while defending or extending its territorial scope on the margins?

BS: Well some people might say: “Look, if your conception of the liberal order doesn’t appeal universally, and doesn’t apply everywhere, then we need to throw it out altogether because it’s just a myth.” But David and I reject that argument. We prioritize fortifying this liberal order internally, both by strengthening democratic forces within each country, and by strengthening the links between democracies — so that we can reinforce each other’s common values of social tolerance, dynamic market economies, democratic flourishing, and respect for human rights. Then in places on the margins, for instance in Ukraine or Tunisia, we can incrementally expand the scope of this liberal order. And elsewhere in the world we can open up opportunities to make gradual progress. We should pursue all of that, even if, in the medium term, we don’t see liberal democracy in Russia or China. And over the next generations, hopefully, the liberal order still can become global.

DM: One big irony from the past 40 years comes from China having benefited so greatly from the liberal international order’s accepted norms, but with that order now having reached the point where a great-power competition (and managing China’s rise) has become a pressing reality. We’ll see more competition between our societies and between competing worldviews going forward. So Bart and I stress the need to strengthen the transatlantic alliance, which undergirds the liberal international order.

Here could you speak to why, even with the important roles that various Asia Pacific nations play in reinforcing this liberal order, the transatlantic alliance still provides the core source of strength — not just for the US and Europe, but for a broader range of international norms?

BS: Good question, and I’d start from a statement made by India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar at last year’s Munich Security Conference, where he argued that if the West doesn’t get its act together, if Europe and America don’t come together effectively, then you can forget about global collective action or meaningful multilateralism — because we still need this core transatlantic engine to drive the greater process. Allies like Japan and South Korea and Australia, as well as partners like India and others, certainly all play key roles, which we outline in this book. But you just have to start somewhere, and we argue that the US-European relationship already has the most established institutional foundation to build upon. You have substantial economic exchange. You have the NATO security infrastructure. You have significant experience with joint action in Ukraine and the Middle East and North Africa.

So we definitely want to keep our vision as open and broad as possible. But to do that you should start from where you already have made the most progress.

DM: Since the end of World War Two, our value system has aligned quite closely with those of Europe. Economically, if you pull back the curtain, you can’t overlook the fact that Europe remains our largest trading partner. Nearly half of global GDP reflects the US and Europe working together. The US invests more in Europe than anyone else does — and vice versa. These shared economic interests make Europe our natural ally on so many levels.

Your book also stresses the unprecedentedly equitable partnership with Europe cultivated during the Obama administration. To outline that more equal model, could we start with the Libya campaign? Of course problematic medium-term developments might make NATO’s Libya intervention today look like an “anti-precedent.” But in which ways did this campaign at least provide glimpses of an exemplary “paradigm of burden-sharing in cases of collective action where America’s security was not threatened directly but its interests and values were challenged”?

BS: Here you can just point to the facts underlying this military operation — with, for example, our NATO allies conducting something like 90 percent of overall air strikes. President Obama pointed to those kinds of numbers, to make the case that the partnership should work this way, with more equitable sharing of responsibilities between Europe and the US, and with a broad range of nations bearing the burdens and costs of peace and security. Of course the aftermath to that initial Libya intervention offers a much less positive example of what to do in international affairs. The country became unstable, and a new source for broader regional violence. But the initial burden-sharing and military operation gave a good example worth keeping in mind, as did the global coalition to defeat ISIS several years later.

DM: Within our own domestic political conversations, the notion of “leading from behind” in Libya worked very much to the detriment of this mission. That phrase sent the wrong message. But Libya actually provided a very strong model for shared leadership, international cooperation, and burden-sharing — which, in fact, is something that most in Congress (on both sides of the aisle) support.

Well for another recent model of equitable burden-sharing, could we consider what the Obama administration got right in calibrating its response to a Ukrainian crisis in which the US “had limited concrete interests…beyond supporting the principles of territorial integrity and state sovereignty”? Could you also sketch how transatlantic burden-sharing in Ukraine raised fresh possibilities for US and EU interests to diverge? And could you describe why today we still should see Ukraine as a “test case for the credibility of Western foreign policy”?

BS: First I’d say that Europe and America stayed joined at the hip in terms of supporting democratic and economic reform in Ukraine, and also in terms of putting pressure on Russia for its aggression in eastern Ukraine and its illegal annexation of Crimea. We imposed significant collective sanctions against Russia. To be fair, those sanctions did not change Russia’s behavior in Ukraine. But they did impose real costs on the Russian economy, and in turn on the Russian military.

So I wouldn’t necessarily say that European and US interests diverged in Ukraine. Ukraine of course is part of Europe, the largest country (in territorial terms) in Europe. That gave an added sense of urgency to European responses. But because of America’s concerns with shaping a rules-based international order, the US also had significant interests at stake. We saw some slight differences in terms of the level of public attention, and maybe the number of visits European heads of government made to Ukraine, versus President Obama. President Obama made a judgment call that he didn’t want to escalate this conflict by going to Kyiv. He didn’t want to fuel further Russian aggression by stoking the fire.

Perhaps, retrospectively, we see that President Obama didn’t always find the perfect balance here. Perhaps he still could have visited Ukraine, as a demonstration of his personal commitment to the country. But that’s all in the past. Going forward, what’s most necessary is for both Europe and the US to recognize Ukraine’s continued importance to our shared strategic interests.

DM: I’d add here that supporting Ukraine should mean not only military assistance, but also economic assistance, and rule-of-law assistance. And in each of these areas, the more that we can coordinate with European allies, the more constructive and effective our assistance will be. So, for example, over the past four years, I’m not precisely sure where US resources and European resources have gone when it comes to reforming the Ukrainian judiciary. But I have to assume this hasn’t been terribly well-coordinated. Moving forward, if we can start working together again, we’ll have a much better chance of seeing the Ukrainian judicial system implement crucial reforms.

So here could you outline your broadest vision, going forward, of transatlantic burden-sharing: both specifically in terms of defense (say in a digital era, with expanding domains of engagement), and also in terms of boosting the liberal order through a wide array of proactive development projects and diplomatic initiatives?

DM: Right, we do need to think carefully here about what it means to prevent conflict. Europeans have been very effective providing foreign assistance, providing development assistance. The US also does this well, but it tends to generate controversy within the American public. Americans often misunderstand the ultimate goals of our foreign assistance, yet that assistance must factor into how we think about overall burden-sharing.

Hopefully we won’t see more major ground wars fought in Europe anytime soon. In much of the world, we’ll more likely see the types of frozen conflict we have in Ukraine — and various kinds of disruptive conflict, as with the Russians engaging in cyber warfare. David Sanger’s recent book describes Europe as a “petri dish” for today’s Russia. The Russians consistently probe various governments and institutions, in pursuit of cyber-warfare advantages. So as the Europeans now bolster their own cyber capabilities, we should work with them. We again should think about this in terms of effective burden-sharing.

More broadly, in our transatlantic partnership, we should keep the focus on a whole-of-government approach. Our relations with Europe do not just focus on NATO, or on trade. We also need constructive interaction on climate, on developing AI technologies, on global health care. For each of these issues, again, we already have a lot in common with the Europeans, and would benefit from working even more collaboratively.

BS: Burden-sharing should be viewed, as you both just put it, as this wide spectrum of defense, development, and diplomacy. On defense, without a doubt, the US spends a lot more. But in hindsight, of course, some of this spending had been directed towards what US officials themselves now consider mistakes, such as the 2003 Iraq war. For 20 years now in Afghanistan, the US has expended considerable troops and blood and treasure, but Europeans also have contributed significantly. And on development, as David pointed out, Europeans recently have spent more than twice as much as the US — though the two sides contributed roughly equal amounts of foreign aid during the inception of large-scale development programs in the 1960s.

So in our book, we encourage the Europeans to spend more on defense. One good benchmark would be the late 1990s, when Europe spent about 60 percent of what the US spent. It doesn’t have to be equal. 60 percent would still mean a significant enhancement of European capabilities. And on the US side, we call for an increase in development aid. Again, this doesn’t have to mean fully catching up to European levels. But the US definitely should spend more than half of what Europe contributes. With Samantha Power at the helm of USAID, we see a good chance for that to happen.

Thankfully we’ve made some headway here without referring to Donald Trump. But which points of comparison (and of contrast) do seem most salient in thinking through relations between Trumpism in the US, anti-immigrant populism in Western Europe, and resurgent authoritarianism in Eastern Europe? How might you see each of these forces, for instance, exploiting legitimate grievances about structural economic conditions, but without offering viable domestic or global solutions? And in terms of a broader transatlantic package, how might you expand on this book’s suggestion that “The two issues of income inequality and international trade should be linked in future U.S.-EU talks as a way of ensuring continued public support for further…liberalization”?

DM: Alongside income inequality, President Biden finds at his doorstep a number of significant controversies and concerns around systemic racism, gun violence, bitter partisanship, a dysfunctional political system. Our country has a number of serious challenges to tackle all at once. Richard Haass wrote a couple years ago that our most effective foreign policy in many ways starts from healing our society at home, and doing as much as we can to deal effectively with domestic issues. And the Biden administration appears to be off to a positive start at addressing some of these just enormous challenges. They’ve hit some minor bumps in some places. But they’ve gotten off to a good start in terms of this global pandemic, particularly by putting forth a bold vision for getting COVID under control in the US. I sense that they’ll achieve much of what they’ve set out here. And nothing works better than success to motivate the American public to get behind a leader.

Clearly, then, income inequality will still pose huge challenges. It already has fueled this populist impulse — and, as you point out, not only in the US, where it has been particularly rampant. We also do see additional contributing issues in Europe, including immigration. So populism does stand out as particularly noteworthy in the present moment, but the broader challenges between democracy and authoritarianism are not new. We’ve faced them before.

BS: Our book includes these quite remarkable statistics on how US levels of income inequality have just ballooned since the early 1980s, since the Reagan administration. In Europe, on the other hand, inequality increased a little bit in the early 1990s. But actually, overall, income inequality diminished in Europe in the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s, with large parts of Central and Eastern Europe integrated into the greater EU. This European experience shows conclusively that you can have globalization, that you can have trade and investment with the rest of the world, that you can become more prosperous as a result — and that, at the same time, you can share those gains with all sectors of your society, with everyone.

Here I find the Biden-Harris team’s notion of a foreign policy for the American middle class so important. We absolutely need to deal with these problems of income inequality in the United States. And we know definitively that you can do this while remaining an open society, with free and fair trade — because others have done it.

Pivoting back then to broader global dynamics, here specifically UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ concern that, for our current multipolar context, the “greatest danger is not conflict due to power struggles but, rather, the prospect of perpetual instability in a world with no global leadership, no rules, and no norms,” how might you see Russia in particular playing a spoiler role — preventing any such stabilizing global leadership from establishing itself? And what kinds of coordinated transatlantic responses to these Russian provocations might you recommend?

BS: The clearest example here comes from 2015 and 2016, when Russia intervened with heavy military support for the Assad regime, and turned the tide in Syria’s civil war. All of a sudden, certain people in various parts of the world, particularly Europe, started misperceiving Russia’s role as potentially helping to resolve that civil war, or helping to resolve Europe’s terrorism threat from ISIS, or Europe’s mass migration problem (which arose in part due to the Syrian conflict). But on each of these issues, Russia in fact countered Europe’s interests — by exacerbating the Syrian civil war. Russia didn’t target ISIS as part of its counterterrorism operations, but instead treated all Syrian democratic opposition forces as terrorist groups. Russia actually tried to foment the refugee flow from Syria into Europe, as well as from other regions into Europe, as a way of destabilizing the EU. But you still had numerous leaders in Europe and beyond thinking: Well, Russia needs to play a part in the solution here, because they’re so engaged. At the 2019 G7 summit, European leaders even expressed interest in inviting Russia to the following summit.

Over the past five or 10 years, we haven’t seen a single situation where Russia constructively helped to resolve one of the world’s pressing problems. Now, let me perhaps caveat this slightly, with the recent news of the Russian COVID vaccine. If it works, and they can produce and distribute it at scale, great. But whether in Syria or Libya or Ukraine or Venezuela, Russia has tended to play a destabilizing spoiler role rather than a constructive role. We will need to confront Russia where we must, while cooperating with it where we can.

DM: In terms of a policy approach that will effectively confront Russia, we’ve already heard a very different tone from the Biden team than from the Trump administration. In his Department of State speech, President Biden said that the US will no longer be “rolling over in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions.” When asked which tools the US has left in its toolbox, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan pointed to a number of individuals yet to be sanctioned, a number of Russian corporate enterprises that still could be targeted. He said the US and Europe still have plenty of tools. Of course the US and Europe have a lot of work ahead to get back on the same page for all of this. But for the first time in four years, we have the potential for coherent strategic diplomatic coordination.

Turning then to the more foundational, transformational challenges posed by a powerful China promoting its own (non-liberal) notion of global order, first what do both US and European policymakers have to understand about how increased engagement with Asia Pacific nations need not mean devaluing the transatlantic partnership? How, for instance, might the TPP have operated on behalf of a much broader liberal order? And what should the US itself better recognize (say in the wake of the EU’s recent Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China) about Europe’s own nuanced relationship to this part of the world?

DM: In terms of managing China’s rise, working with our transatlantic partners will be essential. We can’t address our challenges with China by drifting away from Europe. We in fact need to engage Europe to balance China more effectively. There’s clearly a debate going on in Europe about all of this. But in China today we see not just a rising power, but an authoritarian leader with a clear vision and strategy for increasing Chinese economic and military leverage around the world. And you’ve pointed to the recent economic agreement that Xi Jinping and Angela Merkel signed, which still has to go through multiple stages before being ratified. But that agreement already does indicate a new level of China competing with us now in Europe. That will demand a degree of focus and coordination with Europe which perhaps we haven’t had before. But I’m convinced the Biden administration understands this.

BS: And obviously any long-term strategy for China’s rise will demand complexity, and likely will evolve over time. But we probably can outline the general principles right now. First, we likely won’t have much leverage to change China’s overall trajectory, because it’s such a large country and large economy, with so many different domestic drivers determining where it will end up. But we can of course shape our own behavior, and continue shaping international institutions and global affairs in ways conducive to liberal values of democracy, human rights, rule of law, and market capitalism. We can tilt the balance further away from authoritarian models, and back towards liberal principles.

The TPP offered a very strong example for how to economically integrate the US with a large number of Asia Pacific countries. We’ve heard talk about either the EU or maybe now first the UK joining the CPTPP. The EU also has pursued its own economic agreements with a number of Asian countries. All of these diplomatic efforts offer ways to establish certain norms and rules with the rest of the world, before China locks in its own approach. For many countries, the short-term commercial incentives that China can offer will be quite compelling. But the long-term costs, in terms of reshaping your political structures and making yourself dependent on China, will be quite expensive as well.

In Europe, as David said, we now see an open debate on these questions. President Macron gave an extensive interview at the Atlantic Council, where he argued that Europe (or at least France) should not need to choose between the United States and China, and should perhaps position itself as equidistant between the two. Obviously, Europe and France share values much more closely with the US than with China. But Macron made the argument for maintaining a more neutral or balanced position. Again that’s probably an easy short-term decision, because it entails few costs. But in the long term, this would significantly damage Europe and the US and the wider liberal order — because we really do have to join forces to confront complex challenges such as today’s China.

Well taking everything discussed so far as our context, could you lay out the intellectual groundwork for a new Atlantic Charter, and for the “principled pragmatism” of its basic pillars? And then in terms of concrete institutional arrangements, how do you see a Transatlantic Council, guided by a Transatlantic Strategic Partnership, offering “the flexibility of the G7 while providing a more inclusive membership and agenda”?

DM: Both Bart and I, as policy planners, consider it very, very important to develop a broader policy vision, before you put up the institutional scaffolding around it. So we spent quite a bit of time talking through the history of the original Atlantic Charter. We looked back at the 1941 meeting between FDR and Churchill, laying out the charter. We pieced together how, really from that initial vision, a number of international institutions emerged. The postwar world really evolved out of this charter.

So we sensed the importance of thinking through something similar here. We faced the obvious question of: who should the United States negotiate a new Atlantic Charter with? And we didn’t reach an entirely clear answer, to be honest. But the European Council President Charles Michel has also recently called for a “new founding pact” for the transatlantic partnership.

BS: At the center of our book’s cover, there’s a big blue sky — hopefully evoking the spirit of a “blue-sky memo.” In US government, a blue-sky memo should be ambitious (perhaps even visionary) in its policy recommendations, but still realistic enough so that with sufficient political will it can get implemented. We essentially consider this book a long-form version of a blue-sky memo, and wish for our recommendations to be read in that spirit: as ambitious but realistic, principled but pragmatic.

To trace the logic behind our Transatlantic Council proposal, I’d point readers to the book’s appendix, where we lay out a number of statistics tracking the distribution of world resources over time. Where material resources were located of course played a key role in where power resided. In 1945, power basically resided in the US and UK, which accounted for nearly 50 percent of global GDP, and 75 percent of global military spending. So Roosevelt could partner up with Churchill to draft the Atlantic Charter, and they could seek jointly to ensure the preservation and promotion of liberal values — both in their own societies and gradually elsewhere around the world. Over time, the guiding question evolved to: where else in the world can you amass sufficient economic and military and diplomatic weight to build similar political and institutional structures?

Then fast-forwarding from 1945 to 2020, we saw a distribution of resources still concentrated within America and Europe, as well as Japan and Canada — which all taken together account for about 54 percent of global GDP and of military spending. So we call for a new Atlantic Charter because we understand the need to broaden the tent, and to formulate shared principles of cooperation on facing modern challenges. We call in the first instance for a Transatlantic Strategic Partnership agreement between the US and the EU, but obviously including Canada and the UK, as well as Japan potentially, and other allies like South Korea and Australia. We see no reason to exclude these partners. We hope for a kind of renewal of vows, a restatement of the principles that bind us together — not as some rhetorical exercise, but as a way of focusing the mind on certain core values we need to preserve, and certain joint actions we need to undertake.

In terms of new institutions, we call for a Transatlantic Council bringing together all member states of NATO and the EU, as well as the leadership from those two bodies. We could also think about bringing in leaders from Japan, South Korea, and Australia, as part of this big-tent approach to consultation and coordination. Now, David and I will be the first to concede that the larger this group gets, the more difficult it may become to coordinate joint action. But we believe that, in practice, this institutional structure would remain quite workable. Again we have recent precedents such as the global coalition to defeat ISIS, or the Nuclear Security Summit, each of which had more than 50 members. These initiatives show how you can get good outcomes from a larger body.

The Transatlantic Council wouldn’t require its own building and secretariat and all the institutional infrastructure. Instead, it can adopt the flexible models of the G7 or G20. But in contrast to the G20, we wouldn’t think of Russia or China as good candidates for the Transatlantic Council — because they pose some of the primary challenges requiring joint action by this wider group.

Now, in terms of the Transatlantic Council, some of our closest friends and colleagues can be institutional skeptics, who sometimes have the reaction: “Oh no, not another institution. Not another bureaucracy. We already have enough.” To them we would respond that Thomas Jefferson once pointed out how each generation of leaders and citizens inevitably determines its own political norms and priorities, in light of historical experience, and with a view to the future.

You actually can see this play out over the past 70 or 80 years. NATO emerges in the late 1940s. The European Community emerges in the late 1950s. The G7 emerges in the 1970s. A plethora of institutions emerge or expand in the 1990s and 2000s, say with EU and NATO enlargement. You have the OSCE, the Community of Democracies. You have the G20 in the late 2000s. And now we think that this institutional structure needs another update. We now need to write our own chapter in history that responds to the challenges of our time. The Biden-Harris team has pointed out the underlying truth that America’s just so much stronger when our allies and partners in Europe and Asia work with us, especially in response to our biggest challenges. So we think the current moment is ripe for a new institution such as the Transatlantic Council.

Returning here briefly to the Obama era, you describe certain transatlantic initiatives running out of steam back then: “high-level political attention did not translate into concrete deliverables, and over time, better return on investment appeared elsewhere.” So if we now hope for a reinvigorated partnership, what kinds of tangible goals and significant deliverables stand out? And how to keep a substantial part of the diplomatic focus on pursuing such deliverables going forward?

DM: Well, the book closes with reflections on five of our broadest challenges, in terms of climate, global public health, technology, cyber, and trade. And we think of the Transatlantic Council as the perfect vehicle for taking up those kinds of challenges. Again, these issues require a whole-of-government approach. So from our side, we would want not only the Department of State involved. We’d want Health and Human Services, and the EPA, providing their own expertise. We’d want US officials on this council working consistently with their European counterparts, sharing information and ensuring transparency. That all seems crucial for future progress.

BS: To illustrate this need for new institutions, consider the COVID-19 pandemic and the production and distribution of vaccines. We’ve seen quite remarkable differences over the past few months between the US and the UK accelerating efforts to vaccinate their respective populations — whereas the EU has proceeded at a much, much slower pace, largely as a consequence of multiple missteps last year by various European officials. In our model, a Transatlantic Council could address complex public-health concerns and provide consultations between respective Centers for Disease Control, and other relevant actors. We’d see a lot more proactive exchange of information and analysis, and hopefully faster and more effective responses.

People outside of government often under-appreciate how effective institutions help policymakers process information and make necessary decisions so much faster — compared to ad-hoc approaches when some unanticipated crisis comes along. When you need to establish an ad-hoc global coalition to defeat ISIS, that process itself takes up crucial time. But when you have effective institutions already in place, when you know who to call, when you have an element of mutual trust already established, you start off from a much better position.

Here then for one closing longer-term example, why do we need (and how should we envision) a coordinated transatlantic approach when it comes to emerging technologies, especially AI-enhanced technologies — again especially to keep pace with a massive, data-rich China? And more broadly, how do we avoid a scenario in which the escalating rhetoric around an apparent Chinese “threat” becomes its own self-fulfilling prophecy?

BS: The world’s technological capability right now resides predominantly in the US, as well as in China. Europe has potential, but has been a bit of a laggard region. On the regulatory side, however, we’ve seen the quite extensive regulatory reach that the EU and Europe at large can exert, in terms of shaping new standards and norms that any global tech firm will need to abide by, even if they remain based elsewhere. Perhaps the best example of this so-called Brussels Effect (whereby, due to the European economy’s sheer size, many multinational firms will adopt the EU standard as their global standard, for efficiency’s sake) is the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). These data-privacy rules established in the EU gradually have spread elsewhere around the world, in part through adoption by individual companies.

So if you combine US tech innovation and European regulatory reach, you get quite a powerful vector to shape the broader global economy. Obviously China has its own very rich pool of data, and doesn’t have the same restrictions in terms of accessing this data. But we do have our own competitive advantages.

We’ve discussed China quite a bit today. But our argument of course isn’t to confront China for its own sake. In a number of important areas, such as climate change and COVID and global pandemics, we can and should consider China a potential partner — even as it operates as a competitor or potential rival on other issues. Fundamentally, this book calls for staying clear-eyed and level-headed, recognizing our core partners in Europe and Asia, prioritizing shared common values and interests, and reinforcing our institutional cooperation.

DM: Right, none of the major challenges that we mention at the book’s end fit into this narrow frame of “the US versus China.” Each of these global issues (whether climate, or public health with COVID, or AI, or cyber, or trade) has huge implications for all nations of the world. They each have the potential to bring huge benefits to humankind. And they each could be used nefariously. So the entire global community has a vital interest in a functioning rules-based system.

We don’t seek to set up some fundamental struggle between the US and China. But we do believe that the US can best advance this cause of global well-being, particularly through a strong and active and transparent transatlantic partnership. If and when we face competition between the US and China on certain issues, this partnership will play a crucial role in helping us to meet those challenges. But again, on climate for example, there’s no reason to frame this as some zero-sum contest or confrontation. We may compete with China on certain aspects of climate technology, or AI, or global financing. But in terms of the science, we also need transparency and collaboration. We ultimately should want to help each other.