Anyone interested in Jane Austen’s earliest readers and reception owes a debt to organizational expert Marie Kondo.

Cheap 19th-century reprints performed the heavy lifting of Austen’s early literary rise, starting in earnest in the late 1840s with the Victorian forerunners of the modern paperback — sold in glazed paper boards at railway stations and book stalls. Such shoddy volumes, however, rarely made it into the collections of scholarly libraries. Although printed in the greatest numbers, the cheapest versions of Austen’s novels were, instead of being preserved, read to bits, recycled, or pulped in paper drives. In recent years, however, hard-lived survivors of old reprints have surfaced among the flotsam and jetsam of eBay offerings, charity shops, and second-hand bookstores. While these unwanted 19th-century books apparently failed to spark joy for some, for me they have opened new avenues of research into Austen’s early readers.

This is because some ownership signatures and gift inscriptions left behind in these copies can be traced. Resources such as Google and Ancestry.com have lowered the costs of provenance research so that bare names and dates can be more easily wrapped in biographical context. As a result, mundane copies can supplement the highbrow evidence by which scholars have traditionally tracked reception — adding to published book reviews and the commentary by famous readers duly preserved in archives. Now, the most down-at-the-heels or ill-printed versions of Jane Austen’s stories can bear witness to her popularity amongst a hitherto unreckoned set of ordinary readers. The decluttering craze is democratizing reception history.

We already know that cheap books mushroomed in the 19th century due to innovations in printing, binding, and paper-making that radically lowered price. New distribution networks made possible by railroads did the rest. It may surprise even hardcore Austen fans, however, to learn that the names found in many surviving copies allege a working-class fan base for Austen in the latter half of the 19th century. It turns out that potters, coal miners, and the children of the working classes who received her novels as school prizes made for a substantial group among her early readers. Holding their copies in my hands during my research, I finally felt I had access to that phantom “19th-century reader” whom scholars (myself included) tend to invoke. The names written proudly inside even the most modest of these cheap 19th-century copies imply that book ownership was a badge of educational ambition and achievement — irrespective of the low monetary value of the book itself. When such proud claims are supplemented with gift inscriptions or the names of subsequent owners, Austen becomes part of an important legacy of reading for the working and lower-middle classes.

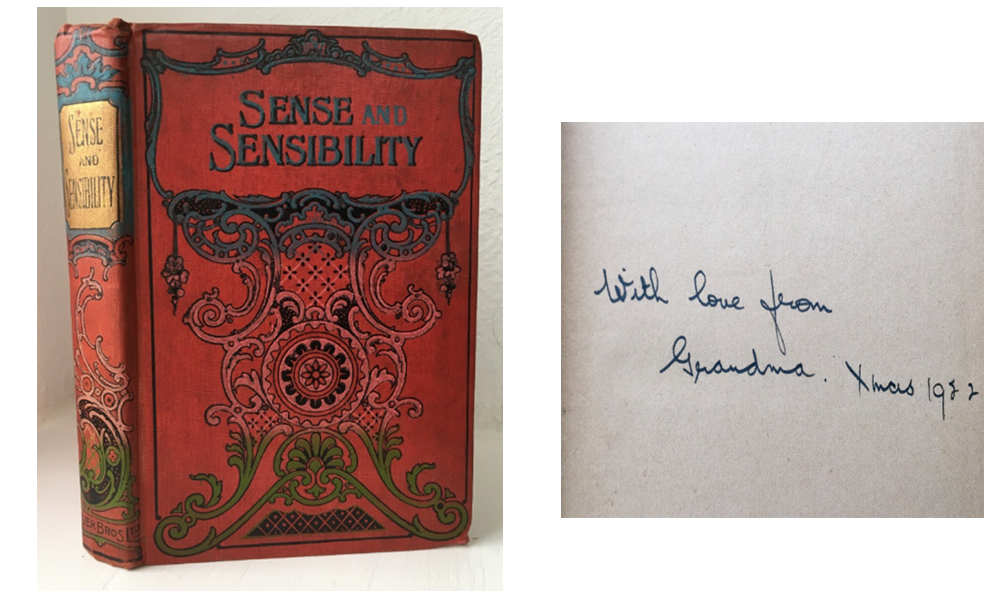

Even without names, of course, gift inscriptions can record the poignant recycling of books across generations. “With love from Grandma. Xmas 1922” appears in a cheaply-produced promotional copy of Sense and Sensibility offered by the Lever soap company in the 1890s as a giveaway to youngsters under 17 in exchange for soap wrappers. For reasons of economics or sentiment, grandma regifted a decades-old book “earned” by collecting soap wrappers during her youth. How, I wondered, will any of us continue this type of Austen legacy if we now enjoy her on a Kindle?

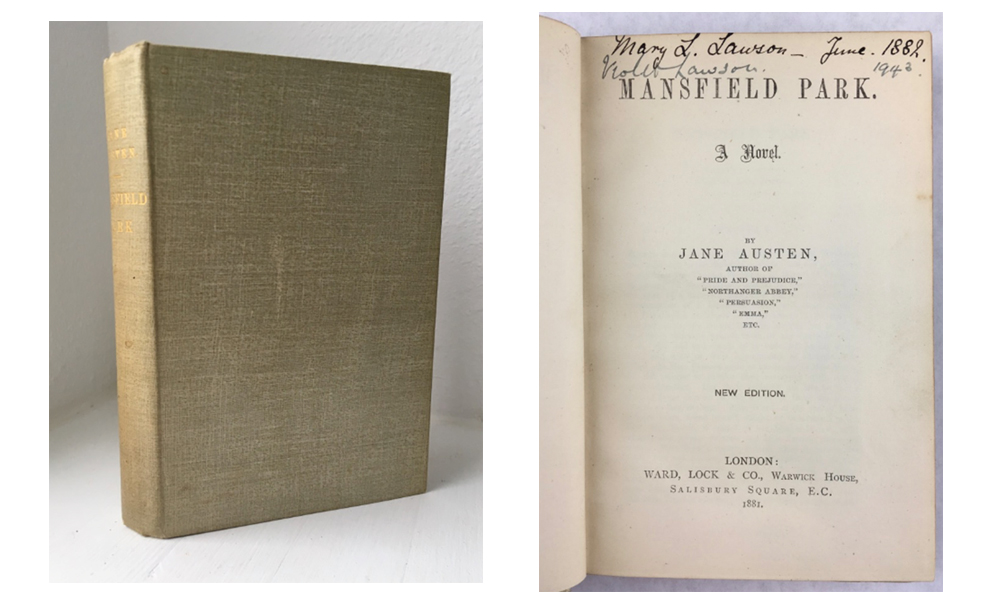

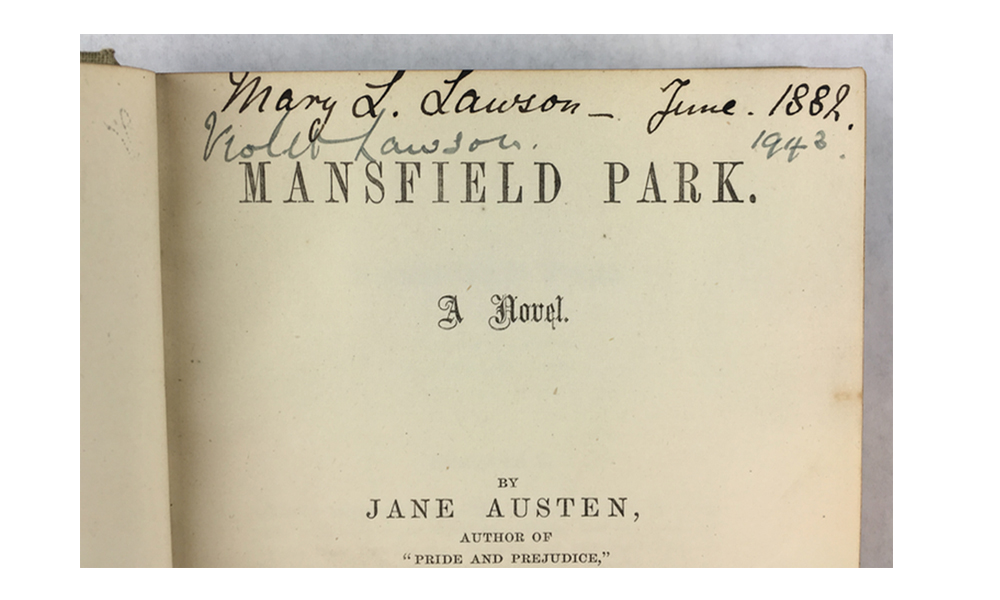

With a little luck and when an inscription in an old book provides an uncommon name plus a location, I found I could track the surnames in census and birth records, conjuring up the lives of Austen’s real readers. Take the plain-Jane shilling reprint of Mansfield Park from 1881 published by Ward, Lock, & Co., a Victorian publisher specializing in inexpensive reprints. This lackluster reprint has the cheek to call itself a “NEW EDITION,” even though it was printed in 1881 from old stereotype plates that had, starting in 1833, been worked hard for close to half a century by at least three publishers to churn out identical copies of Austen dressed in different binding styles. At the top of the title page, the confident ownership signature of “Mary L. Lawson” is written in brown ink, along with the date of “June. 1882.” Underneath, in pencil, is the signature of “Violet Lawson” and the additional date “1943.”

Written sixty-one years apart, the two parallel ownership inscriptions suggest the tenacity with which some books, no matter how inexpensive or unimportant the edition, tend to stay in a family, handed down from generation to generation or simply taken up from a dusty family shelf during a spell of wartime boredom. The 1881 census finds 23-year-old Mary L. Lawson employed as a live-in servant at “Freshford Villa” located at 1 Wandle Road in London’s Wandsworth district. Did she identify with the novel’s heroine, poor Fanny Price, relegated to an attic room? Women remain hard to track in census records, especially if marriage changes their name, and I soon lost sight of Mary. Perhaps Violet, six decades on, was her distant niece? Whatever their connection, Violet Lawson need not have known Mary personally to inherit, or appropriate, her book. It is the neat manner in which Violet has subserviently placed in pencil her own name beneath that of her presumed relative that implies an intellectual kinship. This lackluster copy, then, is Austen as glittering intellectual inheritance. Since my research into cheap reprintings wants to claim a historical value for books that have been ignored by academics who (like me) are trained to focus on precious firsts, “perfect” copies, and “important” scholarly editions, it was heartening to see that many of these now-neglected books had once had steadfast champions — owners who staked their claims on lowbrow versions of Jane Austen with zeal. In doing so, they proudly asserted their own place among her readership.

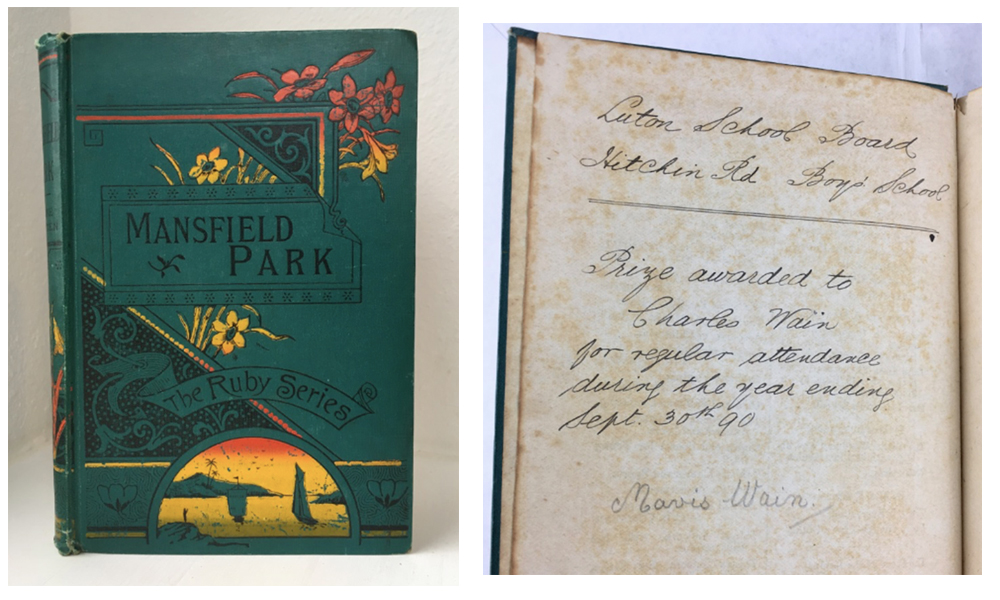

Inexpensive reprints, seasonally tarted up in bright covers by publishers keen to make their old books look perpetually new, became popular prizes in Britain’s Victorian schools. Boys as well as girls received Austen as book prizes for everything from elocution to attendance. Understandably, these trophies were, in working households where books remained scarce, treasured family currency. For example, at a boys’ school in 1890, a young Charles Wain received a Ruby Series copy of Mansfield Park in a long-lived gift series version published by Routledge; an unknown number of years later, Charles Wain’s book was adopted by Mavis Wain, as testified to in her own childlike hand. A daughter? Granddaughter? Although this legacy, too, seems sweet, school book prizes have a dark side. Long after the Education Act of 1870, universal childhood education ended at fourteen, and many of the 19th-century prize inscriptions that I traced proved the last childhood books for their proud working-class recipients. For many laboring boys and girls, a Jane Austen book prize was a passport to drudgery — paid or domestic.

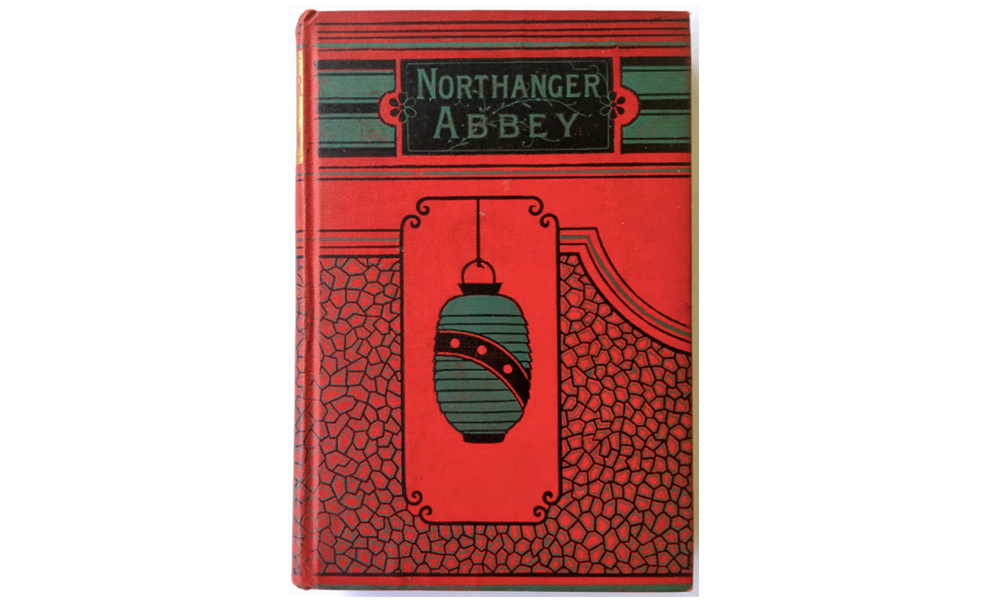

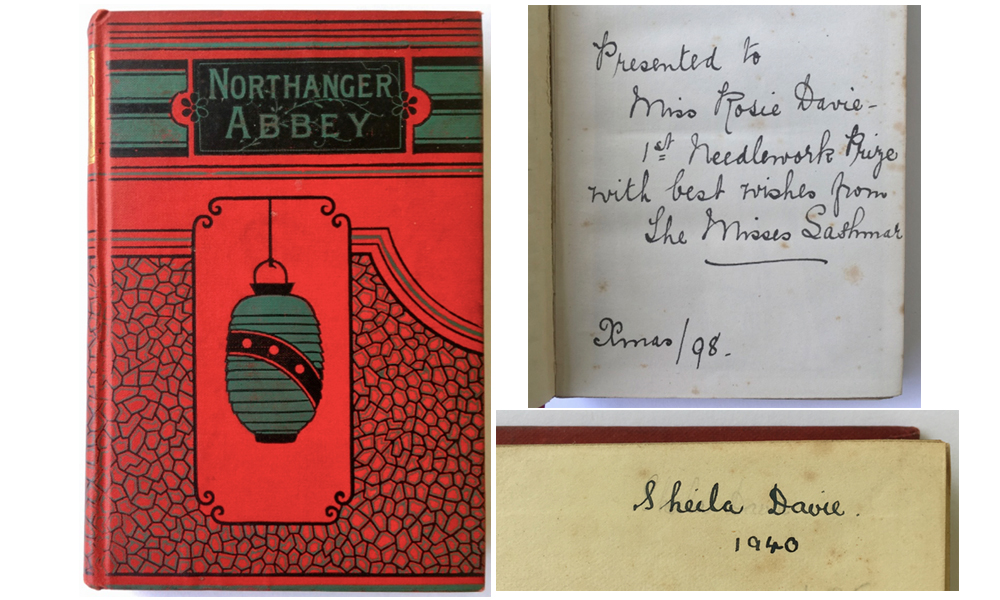

One cheap undated reprint of Northanger Abbey was published by Routledge in a bright red, Chinoiserie-style publisher’s binding, likely during the 1880s when a blissfully short-lived trend dressed English classics in faux Asian costume. The date of its inscription suggests the book may not have been new even when handed out as a prize:

Presented to

Miss Rosie Davie –

1st Needlework Prize

with best wishes from

The Misses Sashmar

Xmas/98-

The UK census from 1891 triangulates the three names to working-class households in Surrey, where Rosalea Davie was the eldest daughter of publicans in Kingston, while Ada and Alice Sashmar lived not that far away in Croydon, daughters of a “Builder.” It seems that seven years later, at Christmas 1898, 14-year-old Rosie was rewarded for her embroidery skill by the Misses Sashmar, then ages 23 and 20, who must have worked as teachers in Surrey. Thirteen years after receiving her Austen prize, the 1911 census finds Rosalea still single, “working at home.” Home was the Public House at 172 King’s Road (her father is grandly listed as “licensed Victualer”). I imagine Rosie tending bar or clearing tables, perhaps still occasionally sighing over Henry Tilney and Catherine Morland.

On a blank leaf inside Rosie’s copy is penned the name “Sheila Davie” in a childlike hand, along with the much later date of “1940” — indicating a new owner with the same last name. Sheila wrote her name neatly in ink, but underneath you can see how she practiced it in pencil first. Sheila (Mary) Davie, who claimed this copy of Austen at the precocious age of eleven, would enjoy different options than her forbearer Rosie. In the census of 1939, her father’s occupation is listed as “engineer instrument maker” while her mother’s is “unpaid domestic duties,” an echo of the feminist protests that suffragettes started in the 1889 census. In fact, the same census page records how most women in the cottages along the working-class street where the Davie family lived took up this rallying cry, with some varying it to read “housewife unpaid.” By 1940, then, this copy of Northanger Abbey had moved north to St. Albans, Hertfordshire, not all that far from the pub where Rosie had labored for her parents in Surrey. Sheila Davie, its new owner, would be surrounded by changing assumptions for women and expanding opportunities.

In sum, thank you, Marie Kondo, for encouraging people all over the world to donate or sell old books. It has been a joy to sift through the spoil heaps for unknown Austens that can provide reception history with new evidence about real readers.

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity (see LARB review, Jan 27, 2013) and the prize-winning Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. She is the creator behind What Jane Saw and has written short essays for The Washington Post and The New York Times. Her new book about unsung editions, entitled The Lost Books of Jane Austen, will be released by Johns Hopkins University Press this October.